by admin | Aug 9, 2019 | Newspaper Report

Utpal Nokrek on wheelchair. | News Link

Looking back at the Garo protestors who opposed the government’s decision to take away their ancestral land in Modhupur Forest to build a commercial eco-park

It was January 3, 2004. I was only 18. I joined a rally to protest the construction of the so-called eco-park within the Modhupur National Park—built on what we considered our ancestral land.

We assembled at Jalabadha-Rajghat in the south of our village, Beduria. This is where the Forest Department was constructing walls that would block our free movement. From there, we were supposed to march to Gaira in the Modhupur National Park, another Garo village in the south. But before we could go any further, our rally was blocked by Forest Department officials, forest guards, and armed police.

The law enforcers fired rubber bullets, at first. Then, as we were running away, they fired real bullets at us from behind. Piren Snal, 28-year-old Garo youth from Joynagachha village next to Beduria, was shot dead on the spot.

I fell to the ground. For a brief moment, I saw others running. Then I blacked out. When I regained consciousness, I found myself in a van—whether it belonged to the police or the forest guards, I do not know. I was soaked in blood. I could not move my body. Piren Snal, dead and covered in blood, was lying on my side, a bullet lodged in his chest.

“One has died and one is alive,” I heard the forest guards saying.

I lay there for hours—it was as if I was left to die. It was late afternoon when they finally removed Piren’s dead body from the van. With me lying face down on the floor, and a forest guard and policeman sitting on a bench, the van began to move towards Tangail or Dhaka.

It was such a painful journey on the bumpy road that I thought I would die. I wished I would die. I felt an excruciating pain in my back and chest. It was January, the coldest time of the year. I was shaking uncontrollably. It was somewhere near Modhupur that they gathered some straw from the ground and threw it over me.

Finally, we reached the Tangail Sadar Hospital. There, doctors located the bullet inside me but could not take it out. They concealed the bullet hole with a bandage and sent me to Dhaka.

I was lucky to be taken in an ambulance from Tangail to Dhaka. I was still in much pain. I was taken to National Institute of Diseases of the Chest and Hospital in Dhaka. Our ambulance arrived at the hospital in the dead of night. There was no surgeon at that time, so we were told to wait till morning.

I was screaming in pain. In the meantime, Dr Abdur Razzaque, the MP from our constituency, arrived. It was under his influence that the surgeon and his team assembled and the hospital got ready for an operation. The bullet was taken out at around 3am. It was not easy. The bullet had gotten stuck in my flesh and bones. The surgeon crudely cut the hole, without anaesthesia.

The next morning, the then forests and environment minister, Shajahan Siraj, came to see me. “You have nothing to worry about. You will get your treatment,” the minister tried to console me.

I did not have any feeling in the lower part of my body. A nurse brought a pin; she poked my leg. I felt nothing.

After a second surgery, this time with anesthesia, the doctors concluded that my spinal cord was permanently damaged. I was paralysed for life.

My life on wheelchair

From Dhaka Medical College I was taken to the Centre for the Rehabilitation of the Paralysed (CRP) in Savar. My life on a wheelchair began.

While at Dhaka Medical and CRP, I was always guarded by the police or forest guards until I took bail in a forest case, which was filed against me after I was shot. Apparently, I was accused of causing hindrance to the FD’s work!

People at the Forest Department started pressuring me and my family to take bail. While I was still at CRP, they took me to Tangail Forest court in a microbus and asked me to sign some papers that would ensure my bail. I refused because there was no one from my side—neither my parents nor a lawyer. My refusal angered the people at the Forest Department. They sent me to Tangail jail for a night and day. You can imagine what an experience it was—in jail, in a wheelchair that I was only just beginning to learn to manoeuvre.

My parents came to court the next day, secured my bail, and took me back to CRP.

All these years later, the forest case is still active. The police visited a few times to remind me that I am not appearing before the Forest Court in Tangail. Every time they came, they made me pay for the octane of their motor cycles.

Thirteen years have passed since I was shot, but I have not been able to file a case yet. No one from the Forest Department has ever come to see me and I have received no support from the government. All the assistance I received—a one-room building to set up a grocery shop and some cash—came from NGOs. My parents now run the shop.

Every day, I follow the same routine. I get up at 6am in the morning. I need about three hours to complete my morning rituals—go to the toilet, brush my teeth and bathe. I cannot do things like other people. I use a catheter every time I urinate. I have to guess when I have to urinate because my bladder no longer functions properly. I eat twice a day—breakfast at 10am and dinner at 7pm. I normally do not eat anything in between.

Once I realised I am permanently settled on a wheel chair, I lost interest in continuing my studies. I am unable to work. My parents and siblings take good care of me. We do not have much land, but we manage.

What has been done to me cannot be undone. All I want now is peace in our ancestral land.

As told to Philip Gain, researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD)

by admin | Mar 8, 2019 | Newspaper Report

Purna Chisik and Satendra Nokrek have four daughters—Francila, Malita, Nomita and Malina—and two sons—Parmel and Sebastin. All six of the siblings have taken their family name, ‘Chisik’ from their mother Purna Chisik. This is normal for the Garo, the leading matrilineal society of Bangladesh.

In the Garo society, each individual belongs to the kinship group of the mother, not to that of the father. Daughters inherit land and other property. However, all daughters are not equal heiresses—one daughter, generally the youngest one, is chosen as nokna who inherits property and cares for her parents. Other daughters get land and other property, according to the wish of the mother. The sons get a tiny share of property, also at the discretion of the mother.

Purna Chisik of Dharati village in Kuragacha union in the Modhupur sal forest area selected her youngest daughter Francila Chisik as nokna. When Purna Chisik died in 2006, she left all her land—around 27 acres of chala (high) land and 6.9 acres of baid (low-land)—to her four daughters and two sons. This land amounts to 113 pakis (one paki is 30 decimals).

Her two sons were less fortunate in getting a share of their mother’s land—each getting two pakis (60 decimals). Three daughters—Malita, Nomita and Malina—got 3.3 acres each. The youngest daughter, Francilia Chisik, the nokna, got the rest, the biggest share of her mother’s property. Satendra Nokrek, Purna Chisik’s husband, who came to Dharati from another village, is now in his nineties. He lives with Francilia Chisik. He owns no property, but his daughters take very good care of him.

Francilia’s husband, Lipu Nokrek, is nokrom or resident son-in-law in the family. Lipu or their sons will not own or inherit Francilia’s land unless she voluntarily gives it to them.

What we see in Purna Chisik’s family about inheritance of land is more or less a common picture in the Garo society: the daughters inherit land and other property and the nokna gets the largest share. The son generally leaves his mother’s house and goes to his wife’s family as resident son-in-law.

However, the Garo matrilineality never implies that the women rule over Garo society. “It is true that women are owners of property, but protection of ownership and management is bestowed upon men,” says researcher and writer Subhas Jengcham. “It is the men who are omnipresent everywhere in society and they take advantage of all opportunities.”

“But matrilineality does help to give women a different status among the Garos than they have among the patrilineal people of the plains,” writes American anthropologist Robbins Burling in his book The Strong Women of Modhupur.

Burling is absolutely right. Women in the Garo society are equal to men. They may not qualify to become kamal (traditional healer and priest) and administer village courts (shalish), but they play a key role in educating their children, with equal attention paid to boys and girls. They make equal contribution to family income. They are seen working their own land, earning cash from work as day labourers, and drinking their favorite home-made rice beer chu alongside men.

Not all women, however, are fortunate to have enough land to work on, like the four daughters of Purna Chisik. Families having little or no land to work on send their daughters to work in beauty parlours. The Garo girls, young or aged, can travel to Dhaka independently and without a man accompanying her.

According to a 2018 survey of the Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), 1,131 Garo women or 6.8 percent of 16,644 Garo people from 44 forest villages in Modhupur work in beauty parlours. This is an astounding fact. Twin factors—land use change and independence of the Garo women—may have led to a large percentage of Garo women working in beauty parlours. It is to be noted that in Modhupur, a very high percentage of Garo households—from 56.5 percent to 84.7 percent—have leased their land to others, most of them Bangalee businessmen, for paddy, spice (ginger and turmeric in particular), pineapple and banana cultivation (SEHD survey 2018).

In Bangladesh, the only other matrilineal Adivasi community is the Khasi that lives in Sylhet Division. Like the Garo, Khasi women are the owners of land and they inherit their parents’ land.

The children also take their mother’s name. In case of separation of parents, the children stay with mothers in both Garo and Khasi societies.

The land issue among the Khasi is far more complex. In explaining the disputes over land, Gidison Pradhan Shuchiang, a myntri (head of punji) argues, “There are 15 Khasi punjis (villages) in the tea garden areas and we have disputes with the management in three of these gardens (Aslam and Kailin in Sreemangal upazila and Jhemaichhara in Kulaura upazila).”

Shuchiang further elaborates on the bigger land conflict between the Khasi and the forest department. “Eleven of 85 Khasi punjis in the Northeastern districts are well-established with land titles in the names of the Khasis,” reports Shuchiang. “In all but 15 punjis in the tea garden areas and 11 established ones, the Khasis have tension and disputes with the forest department. The Khasis claim they have been living on the land from time immemorial and the forest department gazetted that at a later stage.”

It is the myntri in a punji who is responsible for oversight of the land—a community property—that is distributed among the families. Right now, there are reportedly five women Khasi myntri. Women inherit land and participate in betel leaf cultivation—the key economic activity of the Khasi, sort out betel leaf, handle its sale, keep account books and do all other household chores—but they are perhaps not as vocal as the Garo women. In dealing with land issues with the forest department and the tea garden owners, it is mainly the myntri and males who are seen in the front line.

While Garo women move freely between their homes and cities in search of work and income, the Khasi women stay largely restricted to their punjis and betel leaf cultivation, their key economic activity. The Khasi women are also not seen working in the tea gardens that may be next to their punjis. Both Garo and the Khasi are matrilineal but the contrast between the Garo women and the Khasi women is very dramatic.

However, what is common about both Garo and Khasi is that the overwhelming majority of them are Christians, educated and exposed to the modern world. The men in these two matrilineal societies are also increasingly claiming their rights over property in various forms. Men from these matrilineal societies who have employment and earnings can hold property they have earned in their own names. They can also distribute their earned property equally among children. Many want their inheritance traditions changed, as reflected in the words of Subhas Jengcham—”In the Garo society, we want nokna and nokrom traditions changed so that women and men get equal share in their parents’ property.”

The other Adivasi communities around the country—be it in the plains or in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT)—are all patriarchal and patrilineal. The ownership and inheritance of land among the Santal, Oraon, Munda, Koch and dozens of other ethnic communities in the Northwest, North-center and northeast (outside the tea gardens) are strongly influenced by Hindu law and customs. A woman in these communities does not own or inherit land unless her father or brother has willed it to her. It is only men in these societies who inherit land and property. A woman can use land and property after her father’s death if she does not have brother(s), but even then, it will revert to her uncle(s) or their sons, if any. But one thing about the women in these ethnic communities—from numerous Santal to tiny Kadar in Dinajpur—is that they are seen as hard working, engaged in wage labour and other menial work to grow crops and feed their families.

In the tea gardens, there are as many as 80 non-Bengali ethnic communities with a population of half million. Women constitute more than 50 percent of the workforce in 160 tea gardens in the Sylhet Division and Rangamati; and more than 90 percent of the tea leaf pickers are women. They live in the labour lines in tea gardens. An appalling truth is that they own no land. Of 113,663.87 ha of public land granted for production of tea, 12,291.88 ha are khet or paddy land that the tea workers can only cultivate under restrictions. They do not have titles for these pieces of land. Attempts to take away khet land by the tea garden owners or government have always been a deep concern for the tea workers.

Women in the tea gardens adhere to the patriarchal and predominantly Hindu community and are absolutely landless. Belonging to the lowest rung in the Hindu casteism, they were uprooted from their homes in Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India and had been brought to their current location to work in the tea gardens. Women workers do the most painstaking work in the field picking tea leaf all day. But they are completely bereft of land and property rights including their homesteads and the houses they live in. “In India, Hindu laws have changed significantly and Hindu women have been given right to land,” says Shamsul Huda, executive director of Association for Land Reform and Development (ALRD). “But in Bangladesh Hindu laws have not changed to award right to land and property to women.”

The Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Bawm, Mro, Khyang, Chak, Tanhchangya, Khumi, Lushai and Pangkhua in three hill districts in the Southeast and Rakhine in Cox’s Bazar are also patriarchal. According to customary laws, women in these communities do not generally own or inherit land. But unlike the plains, some variations are reported from the hill districts.

There are also initiatives to reform the customary laws and practices in these communities. “We, the Bawms, have recently reformed our customary laws and are attempting to give a fair share of our land and property to our women,” reports ZuamLian Amlai, former president of Bawm Social Council. “Other indigenous communities in Bandarban are also following our footsteps and attempting to reform customary laws to award rights to the women to land and property.”

Marma women in Bohmong circle (Bandarban) get some share in property. “Sons, daughters and the wife of a deceased person all attain absolute rights over property, which is divided following the Digest of the Burmese Buddhist Law (also known as Shamuhada Law),” says Han Han, a Marma researcher. “However, the wife and daughters of a deceased person (husband or father) in Marma community living in Mong circle (Khagrachhari District) and Chakma circle (Rangamati), do not attain any property right, unless the deceased have gifted or willed it prior to death.”

According to customary law in Bandarban, sons are entitled to get three-fourths of the property while wife and daughters get one-fourth. Sometimes the ratio is modified as ten-sixteenth for the son and six-sixteenth for the daughters. Also, there are examples of Marma households where mutual agreements had superseded the law.

Han Han also reports that in Chakma, Tanchangya and Mro inheritance laws, women have no right to landed property. “Deceased’s son(s) attain the absolute right over his or their father’s property,” explains Han Han. “Deceased’s wife (if remained unmarried) and unmarried daughters receive maintenance from the property. In absence (death) of son, deceased’s son’s wife (widow), son’s son and unmarried daughters receive maintenance until marriage from deceased’s property or directly inherit the property.”

One thing about women and land in the three hill districts is that they are visible everywhere. Their hard work and constant attention are crucial for the maintenance of jum (slash and burn cultivation) in the hills. They are the ones who do most of the harvest and manage the sale of crops from jum and fields. In other agricultural works, sale of labour, and every economic activity they participate along with the men. Their connection with land is symbiotic, which is true of other Adivasi women in the plains and tea gardens. Sadly enough, justice is not done to Adivasi women when it comes to the right to land and inheritance.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

by admin | Jan 25, 2019 | Newspaper Report

A nomadic existence

Philip Gain | News Link

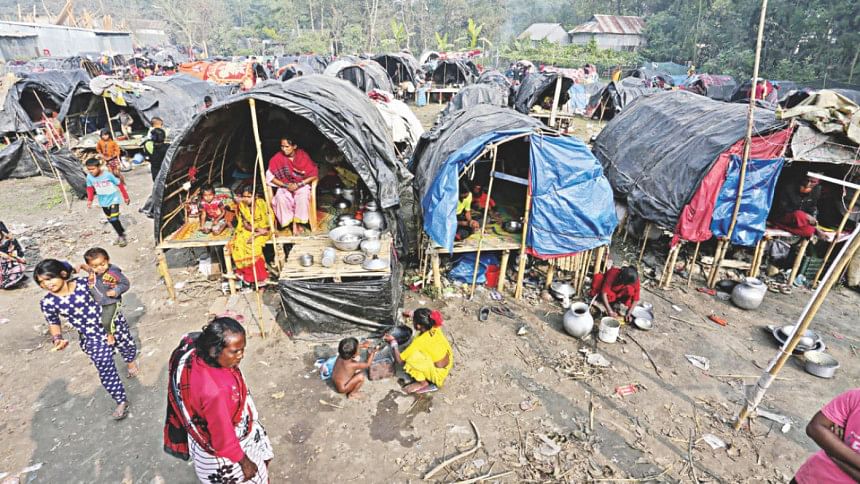

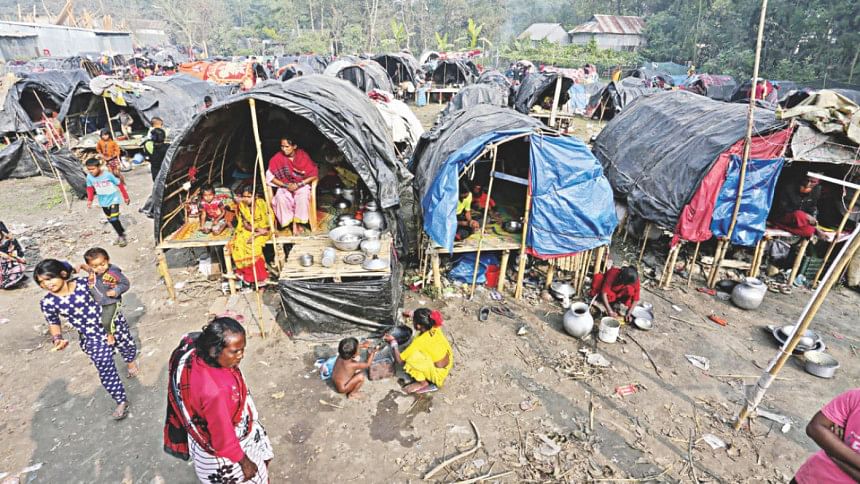

14 Bede families have set up their oval-shaped makeshift tents on private land in Natun Torki, a village in Kalkini Upazila of Madaripur district. A branch of the Arialkha river flows on the west of Natun Torki. The area is well-known in Barishal for Torki Bandar, a narrow but flowing river on the west. The Bede huts are just on the outskirts of the crowded Natun Torki market.

Soud Khan, a Bede Sardar from Kharia in Munshiganj, and two other Bedes—Md Zakir Hossain and Md Nurun Nabi—guide me into their tents, many in the open space and some under the shade of a tree. It is a bright, sunny afternoon in June 29, 2018. Each tent seems to have everything a family needs, all crammed into a 100 to 150 square-feet space. Most tents are also fitted with solar panels. The tents facing west glow in the golden sunshine.

It is Friday, an off-day here. I inspect the tents and take photos in the daylight before finally sitting down for a chat with the elderly Bedes, surrounded by everyone of the little Bede community.

Md Zakir Hossain, in his late forties, informs me that all 14 families there had started their journey from Khari in Munshiganj in October 2017. Since then they have set up their tents and set up businesses in 14 places!

Their journey through these months saw them moving through Shariatpur, Madaripur, Barguna, Jhalakathi and Barishal. Before coming to Natun Torki, they spent a month and ten days in the Doari Bridge area in Barishal.

“We stay in an area for as long as the business is good,” says Hossain, admitting that the business is actually not that good anywhere. “We survive on minimal income and the scope of business dries out pretty quickly. So, we keep moving.”

The 14 families are all Mal Manta, one of a dozen groups among the Bede. One main business of the female Mal Bede is making use of singe, a metal pipe that sucks out bad blood from the human body to give relief from pain. Other businesses of Mal Bede include the search of lost gold, and sale of imitation ornaments, cosmetics, amulets, cups and other light utensils.

Hossain and his group plan to stay at Natun Torki for no longer than two weeks. They do not think business will be good here. I call Hossain some 20 days after I meet them to check if they have moved on.

“Yes, we are now at Haturia Launch Ghat in Goshairhat Thana under Shariatpur district,” he tells me. “We stayed at Natun Torki for 15 days.”

The life of the Bedes is tough indeed. “Because we are always on the run, our children cannot attend school,” laments Rubina Akhtar, 45, explaining that none of the 25 children of the 14 families receive education.

“Many years back, Father Renato, a Catholic priest, used to assist us and had a school that would travel with us,” recalls Rubina’s husband Nurun Nabi, 55, who had been a teacher of the floating school. Nurun Nabi studied up to class ten and is ready to teach the Bede children again.

“Give us a school and a teacher,” Rubina demands of me repeatedly. “We want education for our children.” When I mention that Bangladesh reportedly has a 100 percent enrollment for children, Rubina shouts in disagreement, “It is a lie.”

A large percentage of the Bede is on the move like these 14 families; and their children do not get any education. About 15 years ago, these groups used to glide through the country in boats. Their economic condition was better back then. Now, none them have a boat.

Most of the Bede boats in Kakalia disappears in 2018. Photo: Philip Gain

Most of the Bede boats in Kakalia disappears in 2018. Photo: Philip Gain

The Bede geography

Grambangla Unnayan Committee, a non-profit organisation that works closely with Bedes, estimates that there are 5,000 Bede groups roaming around the country for 10 months around the year. Then they assemble at 75 locations in 39 districts. Normally, they get together during Eid-ul-Azha or national and local elections. Most of them were not allowed to vote until 2007.However, a great percentage of Bede households do not have land or houses where they are registered as voters. They simply carry their tents everywhere.

According to a survey by the NGO, more than 90 percent of Bedes are illiterate. An overwhelming percentage live below the poverty line. Very few children are vaccinated. As they change locations often, they do not enjoy any government family welfare schemes or health assistance. Although they belong to the poorest of the poor and are landless, they hardly get khas land for settlement. Their access to safety net programmes such as old age allowance, VGF cards, disability allowance, flood relief etc. is minimal.

House of a poor Bede in Torki, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

House of a poor Bede in Torki, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

From water to land

Before visiting Natun Torki, we also spend hours at Torki Char Bede Palli. The hamlet is located along a half kilometer stretch on a western branch of the Arialkha river that snakes through Torki Bandar. The Bede hamlet, with its two-storey concrete and wooden houses, is neat and clean. Some houses, of course, reveal the poverty of the 60 families staying there. The shabbier houses are built like boats on plinths, perhaps in fond memory of their long-lost boats. The differences between the well-off and poorer Bede are clearly visible.

Md Nannu Sarder tells me that in addition to the 60 families settled on tiny plots of land purchased as far back as 25 years ago, another 60 to 70 families assembled here on boats for two months in October. Torki Char Bazar is home for them. Some families have small plots of land but they are yet to build houses.

For a month or two in October and November they relax, organise parties with singing and dancing, repair their boats, and settle social matters such as disputes and marriages. “About half of the 70 families who don’t own houses and have their boats under repair set up tents,” explains the Sardar (leader of the Bede hamlet). The hamlet grows lively with the assembled crowds.

But during business season, most working men and women go out to sell their business ware. Some women roam around with singe leaving the hamlet nearly empty. Beside the village, the river flows quietly—lifeblood of the wandering people, eager to settle down as agriculturists.

“But we have been able to purchase only tiny plots of land on which to build our houses,” says Nannu Sarder, his strong features not once reveal his age of 75. “None of us have agricultural land.”

A two-storied typical house of a well-to-do bede in Torki, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

This is a change they want now. “Once we settle down, our children can go to school,” asserts Nannu.

Two of Sarder’s friends—Md Jahangir and Md Abdur Rab—join us as we chat. They reminisce about their life 25 years back, when they all had boats. “We used to come here twice a year since 1972. The river had a magnetic power. We would repair our boats here,” recalls Md Jahangir, 65, who was the first to buy five decimals of land for Tk 40,000 back in the day.

“The local Gale (non-Bede Bangalee) offered to sell land to us,” says Md Jahangir. Others followed Jahangir too.

The Manta of Torki Char Bede Palli in Gournadi Pourashava are all from Amanatganj, Barishal, and all are Muslims. They believe that they are different from Bedes of Dhaka Division and other areas. Soud Khan of Kharia in Munshiganj who accompanied us agrees. “I can see the Bede of Barishal are the homely kind,” observes Khan.

The benefit of a permanent address is clear.

However, even after settling down, they face social difficulties with the Gale. “They look down upon us and do not want to socialise with us,” says Nannu Sarder. “We pray in separate mosques and we do not mix with the Gale who envy our economic well-being.” Relations between the Bede and Gale turned bitter after a fight two years ago.

Like the Bede who have settled in the Torki Bandar area, other Bede groups are also trying to settle on land. One such group is seen in Kakalia village in the Nagari union of Kaliganj upazila in Gazipur. Even a year and half ago, around 60 Bedes had boats beautifully lined up in the Turag river close to the Tongi-Ghorashal Highway. At one time, 200 boats would float in this part of the Turag, serving as a reminder of the river gypsy tradition in riverine Bengal.

But in July 2018, only eight boats were left. Quite a few of the awnings were set on the land close to the river. Others have disappeared from the river with signs of dilapidation around. Around 60 families have now built their houses on khas land on the Turag bank. The majority of the families have built tin shed houses, some with concrete floor. One family has constructed a two-storey home with a wooden deck—a typical house of a well-off Bede family. Others have set the awnings of their boats right on the banks of Turag.

Child being prepared for marriage. Photo: Philip Gain

Mosammat Rezia, 70, born and brought up on a boat, feels sad about the boat life that has recently ended for her and others. She has sold cosmetics and ornaments on foot all her life, a typical mode of work for Sandar Manta women. She has two sons who sell cosmetics and supplement their income by fishing in the Belai beel and river during monsoon.

has sold cosmetics and ornaments on foot all her life, a typical mode of work for Sandar Manta women. She has two sons who sell cosmetics and supplement their income by fishing in the Belai beel and river during monsoon.

“We are destitute,” sighs Rezia. “We have to buy everything except for water.” The families, however, have received two concrete toilets and one tubewell from the government.”

Land and agriculture are mirages to the Bede of Kakalia or elsewhere. 60 Bede families have settled on 51 decimals of khas land; but not for free. Abu Miah, Tabu Miah and Ali have taken yearly leases of 20 decimals of land and divided it into 10 tiny plots. Fazlul Haque, Rezia’s son, took one of the plots for BDT 8,000 15 years ago. Others have taken plots for between BDT 40,000 and BDT 50,000.

It is here that we find Nuru Miah, aged 110. He stoops low, yet he walks fast and his eyesight is perfect. Born in Demra, he came here 10 years back. His wife Gedi Begum is 90 years old. Both husband and wife were born, and have spent all their life, on boats.

A Bede playing been or pungi (flute). Photo: Philip Gain

“Since then we have set the awnings of our boat on land and we live under it,” he says, pointing to the oval-shaped structure that he set up after his boat broke. Everybody in the little hamlet is sympathetic to the aged couple.

A few families in Kakalia that still live there will soon abandon their boats. “We do not want to go back,” says Sadhina Begum, 47, who with a son and two daughters left their boat about a year back.

Sadhina’s son works at a garment factory at College Gate, 10 minutes away from Kakalia. Like Sadhina’s son, 15 other young boys and girls go to work in the nearby garment factory.

Bede tents in a playground in Goalimandra, Munshiganj. Photo: Philip Gain

A much bigger group of Sandar Bede, around 320 families, have been living on the Turag bank attached to the Tongi bridge. It is actually an age-old Bede slum comprising small huts crammed on a narrow strip of public land.

The men of this Bede squalid are in the fish trade. They buy fish from Abdullahpur, Jatrabari, Karwan Bazar, etc and sell it in the local market. “The Turag was wider and clearer in the past,” says octogenarian Ismail, “but now it is too polluted with hardly any fish to catch.” The women, as usual, sell cosmetics and utensils in villages far and near.

Bedana, aged 70, sits in front of her hut in great despair. She has heard that many of the Bede houses would have to be dismantled for the construction of another bridge in Tongi. “We have no land and no means. We do not know where to go if we are required to move out,” says Bedana.

When I checked with Giashuddin Sarker, councillor of Ward No. 57, Gazipur City Corporation, in late September last year, he reported that, “94 Bede families have already been evicted for Tongi bridge construction. They have taken shelter in their relatives’ houses and a few families have gone to Savar Bede villages.”

Other Sandars at Tongi are equally concerned. In fact, this has Bedes all around the country concerned. They want change in their lifestyles. They want to settle on land and become agriculturists. It is a century-old desire as reflected in W.W. Hunter’s writing on Bediyas around a century and half ago: “They mostly wander about in boats, and subsist by jugglery and thieving, but some of them have now settled down as agriculturists.”

However, Bede life on land is not easy. Unemployment and social ills such as drug addiction thrived in Bede villages. But years back, things began to improve with the help of a police officer, Habibur Rahman, then a superintendent police of Dhaka and now a deputy inspector general of police.

back, things began to improve with the help of a police officer, Habibur Rahman, then a superintendent police of Dhaka and now a deputy inspector general of police.

The police official appeared as a great friend to the Bede. “He motivated the drug addicts and dealers in the villages to engage in productive work,” says Ramjan Ahmed, an educated Bede leader from Badda and managing director of Uttaran Fashion, a small garment factory that exclusively employs Bede girls and boys. “Many girls who previously charmed snakes and sold cosmetics now operate modern sewing machines and make clothes for export.”

The factory is also a training ground. “So far 105 girls and boys have been trained and about 50 of them work at the factory,” states Ramjan Ahmed. “The factory keeps training girls with a financial incentive. They seek work in other factories after learning the skills of the trade. This is how many are transitioning from traditional work to modern-day work.”

Bede girls from Munshiganj photographed in Torki Bandar, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

“The profits are spent on the welfare of the Bedes,” says Habibur Rahman, who has a comprehensive plan for the Bedes of Savar in particular. A primary school dedicated for the Bede children is months away. A cluster village on about four acres of land for the landless Bede is becoming visible on the other side of the Bongshi river, which was the life blood of the Bede not long ago.

With Habibur Rahman’s initiative, 36 young people have learned to drive. Many others have passed the test to become police officers and got other jobs. He set up four schools in Khari in Munshiganj, and also helps when Bedes face trouble anywhere in the country.

“I also want to set up a Bede museum in Savar where people will see the Bede artefacts and learn about their history,” says Habibur Rahman with confidence.

The Bedes are clear enough on one thing: they are falling behind in the race for progress. They realise if their nomadic existence continues, they cannot send their children to schools, access public health services and attain skills to move out of extreme poverty. So, their appeal to the state is that they are permanently allocated some khas land or that arrangements are made so that they can purchase small plots in areas they feel comfortable to live in.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

by admin | Sep 2, 2018 | Newspaper Report

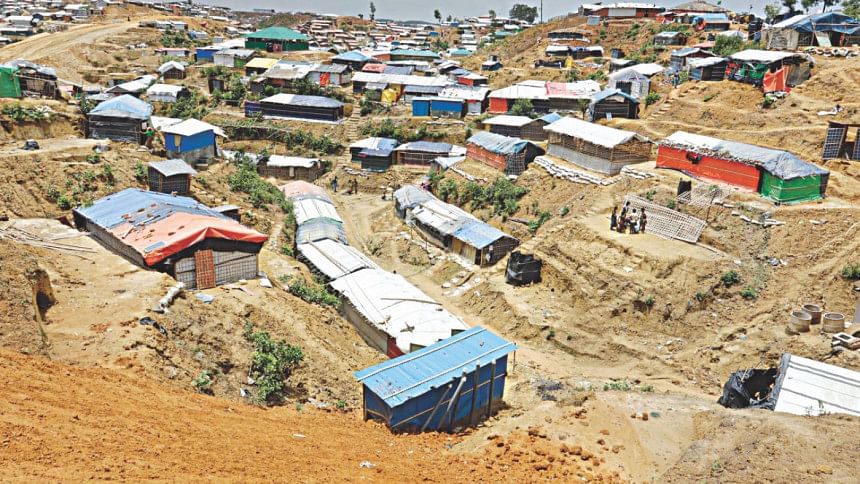

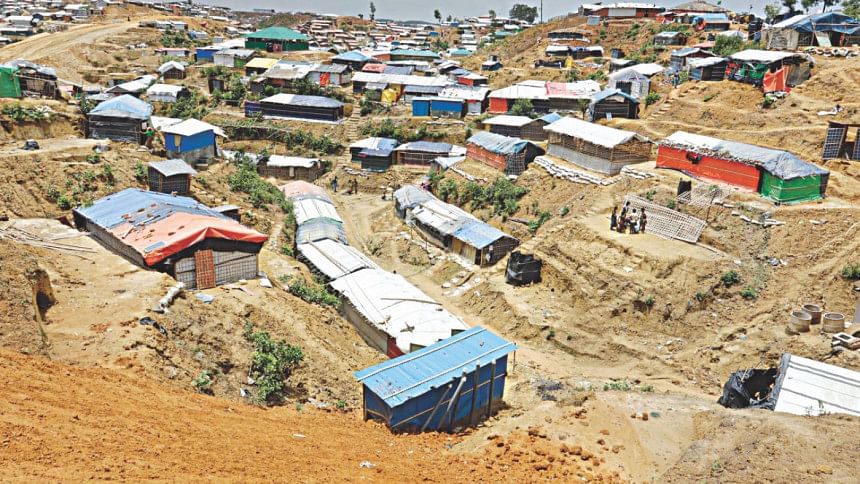

We stand in the middle of Rohingya Camp No. 18. It is in the southwest of Kutupalong Rohingya camp cluster in Ukhia upazila of Cox’s Bazar district. We are stunned. What used to be green hills months ago are completely devoid of vegetation today and covered with tens of thousands of flimsy shelters made of bamboo, polythene, and tarpaulin of different colours. There is hardly any empty space in the hills occupied by the Rohingya.

The hills in the 5,800 acres of forestland (as of early this year) have not only been stripped off of vegetation—natural or planted—they have been thoroughly downsized. Some have been levelled and many partially cut out for construction of roads. Red, sandy mud is piled here and there. The temporary shelters have been built on the terraced hills from top to bottom.

The biggest refugee camp in the world today—Kutupalong—has been split into 24 smaller camps and each camp is designated a number. Of the total 32 camps, other eight camps are scattered in Teknaf upazila.

The landscape that was once filled with songs of birds and crickets and roamed around by elephants and a myriad other wild creatures is thoroughly degraded today. Every inch is now occupied by humans. During the daytime, a low clamour can be heard everywhere and the Muslim call for prayer ring out from the mics of the mosques at intervals.

On May 19 this year, when we stood in the completely ruined forest landscape, we stopped Giasuddin, a young man from Balukhali (a village east of Camp No. 18) to hear how he as a local felt about the abrupt change in his neighbourhood.

“The entire area was jungle with acacia plantation. This is elephant territory,” says Giasuddin with confidence. “I have seen tigers, elephants, and other animals in this area. The jungle was there until Rohingya poured in.”

Monjur Alam, a 31-year-old-Rohingya of Balukhali camp, agrees with Giasuddin. “When we came here nine months ago, it was all good jungle. I myself cut 10 to 12 trees to make space for my house. I saw an elephant the day I came here. The elephant killed two persons of a family,” says Alam. “We used to go to the jungle to collect firewood. But when the rain started, we stopped going there out of fear of elephants and leeches.”

When the Rohingya, in the face of genocide in their own country, had begun to come into Bangladesh from August 25, 2017 onwards, everybody was shocked. The Rohingya influx, with nearly 120,000 people crossing the border per week at its peak, was the highest since the Rwandan genocide (according to an estimate by The Economist).

The land where the Rohingya camps were built was covered with greenery and was under the jurisdiction of Bangladesh Forest Department (FD). The FD officials tried to prevent the Rohingya from occupying the forestland. They did not anticipate then, the sheer number of people that were yet to come. “We were in the field for little over a week since August 25 to resist. But the Rohingya influx since Eid-day (September 5, 2017) was so great that we gave up. We had no time for planning. Our main purpose was to protect people,” says Md. Ali Kabir, the Divisional Forest Officer of Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division.

Environmental degradation continues

The initial days of the Rohingya influx were traumatic for the Forest Department and they watched helplessly as the Rohingya people settled in the forest land in Cox’s Bazar.

What is unique about the district of Cox’s Bazar is that officially 38 percent of its land surface is forestland and in the upazila of Ukhia alone, it is more than 50 percent. According to the office of the Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division, the state of the forest was already perilous even before the Rohingya influx in 2017-2018. Many of the 1991 cyclone victims took refuge on the forest land here in Cox’s Bazar. Development activities required cutting down parts of the forest even before. One example is land acquisition for building a cantonment and construction of the marine drive from Cox’s Bazar to Teknaf. The soil required for the marine drive was actually mined from the hills. The Forest Department did not approve of it but they were allegedly rendered powerless in the face of an ambition such as the marine drive, which after completion, is apparently very pleasing to tourists. But very few are aware of the environmental costs behind it.

The Forest Department also had to give up land for development of Cox’s Bazar town and tourism facilities that the government has been promoting. Meanwhile, the monoculture of foreign species, especially acacia and eucalyptus, has replaced garjan forests, creating a man-made disaster on pristine forest land.

Nevertheless, what happened to the forests of Cox’s Bazar since the beginning of the current influx has been nothing less than a catastrophe.

Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, the only game reserve of the country up until 2010, is just on the south-western border of Kutupalong Camp. The wildlife sanctuary started with 28,688 acres of forest land. According to the Forest Department, some 800 makeshift shelters have been erected in the sanctuary area, which is not that high a number yet, believes FD. “But the Rohingya who had started exploiting the sanctuary from the very beginning of their arrival are grave concerns for the forest and local communities,” says an official.

The destruction of the forest is not just about clearing of trees. The number of plant species and wildlife in and around the camp sites are in danger of being drastically reduced, if not completely wiped out.

According to the office of Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division, Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary alone contained 50 percent of all the mammals found in Bangladesh not too long ago, including the rare Malayan tree shrew and eight of the 10 types of primates found in the country: leopard, golden cat, fishing cat, jungle cat, hedgehog, fox, wild boar, monkey, langur, great hornbill, big grey wood peckers, and Asian elephants. Around 112 different plant species including garjan and evergreen trees and other secondary plant species grew in these hilly areas. Around 64 faunal species with high populations of 10 species of mammals, 40 species of birds, 10 species of reptiles and four species of amphibians were recorded in the sanctuary.

Sadly, the population of the elephants in the Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, considered genetically viable, has now been separated into two groups—35 to 40 elephants are reportedly trapped in the west side of the Kutupalong camp and an equal number on the east. They cannot meet each other owing to the camps closing down the corridor they use for migration. This may prove fatal for the overall population in the future.

The male elephants may not take it easy and they may lose their temper and get violent, says Professor Monirul H Khan of Jahangirnagar University’s zoology department. He is also a wildlife photographer.

“The elephants travel a lot for feeding. The same herd of elephants uses the same corridor for generations,” says Khan.

That elephants may lose temper has already been demonstrated. “It happened seven months ago when a big elephant forayed into our house at 12:30 am. We were asleep. The elephant smashed our house. It killed my two children, four-month-old Yasmin Ara and six-year-old Mujibur Rahman. The elephant stepped on my hip and crushed it. I was given primary treatment at Kutupalong Hospital and afterwards, I took treatment at Malumghat Hospital for a month,” says Nurjahan, 45, propped against the bamboo walls of her makeshift hut in the Balukhali campsite.

Nurjahan cannot walk normally and cannot go out of her house any longer. When we went to see her on June 15, she could only stand using the bamboo pillars of her hut for support. The camps in Balukhali and Jamtoli areas are close to Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary area.

Nurjahan’s two children are among a dozen people killed by elephants.

The corridor for elephants that travel up to Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary from the east has been severely disturbed by the freshly-built Rohingya shelters that currently host a population next to the third largest populated city in Bangladesh. Kutupalong Refugee Camp is not a city but some jokingly refer to it as the fourth largest city of the country.

A new emergency

The entire population of Ukhia and Teknaf (471,768 according to 2011 census) are largely dependent on firewood for cooking their daily meals. They were heavily dependent on nearby forest land for firewood. Now a million Rohingya have been added to this population, thus increasing the demand for firewood.

“Massive deforestation has been taking place. Forests equivalent to three to four football fields are being cleared every day,” adds Paul Quigley, energy specialist of UNHCR in Cox’s Bazar, “They cannot cook their meals if they do not collect firewood.”

The Rohingya first cut down every standing tree in the camp sites (however, there was no traditional garjan to cut; those had already gone). They cut young planted trees, most of them exotic. Then they uprooted the stumps and roots. Everyday Rohingya men are seen arriving with loads of firewood, including stumps and roots of trees.

The current Rohingya influx has significantly affected local communities and their environment. “The host communities—350,000 people living close to the camps—have been directly affected,” says Subrata Kumar Chakrabarty, livelihoods officer of UNHCR. “People of the host communities have lost crops.”

The loss of forest and presence of such a large Rohingya population in Ukhia in particular has been disturbing for the ‘host’, community. “We, the villagers used to graze our animals in the forest, fish in the creeks and small lakes, collect firewood and could roam around the area freely. Now without the forest, there is no grazing land for our cows and goats and we have no access to the area,” laments Giasuddin.

The environmental effects of the Rohingya go far beyond Ukhia as well. Bamboo supplied to the Rohingya for construction of their shelters comes in large quantities mainly from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Ora, mitinga, muli, bariwala (large)—all sorts of bamboo are being cut in excess and sent to the Rohingya camps. This has a negative effect on the environment in the CHT that has already lost much of its glory associated with its bamboo resources.

The loss of top soil in the hills that shelter the Rohingya people is obvious. This intensifies the fear of landslides in the camp sites that have some similarities with the landscapes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). This year landslides have not been a serious issue in the camp site yet, but the risk remains as most of the land has been turned barren increasing the likelihood of landslides.

Simultaneously, huge quantities of synthetic materials such as polythene, plastic and tarpaulin are being used to create shelters for the Rohingya people. And irresponsibly disposing plastic and other non-biodegradable items will be detrimental to the future composition of the area’s soil.

Other sources of concern

Pollution in the form of light, noise, water and air are other severe causes for concern. Artificial light from the camps disrupts the nocturnal activities within the forests and so hinders wildlife reproduction ultimately affecting the species’ population. Noise from within the communities, vehicles moving in the camp site and service providers having suddenly increased further creates disturbances for wildlife in the surrounding areas.

Other serious concerns are related to WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene). Drinkable water is short in supply in Cox’s Bazar, especially in the Teknaf upazila. Therefore, access to drinking water has become even scarcer mainly in these upazilas where the refugees have settled. This will affect both the host community and the refugees, especially during the dry season.

The government is struggling to contain the water and air-borne diseases carried by Rohingya who had limited access to vaccinations and healthcare in their country. Diseases like diphtheria, respiratory tract infection, diarrhoea, dysentery, and skin diseases are very common in the camps, which may cause an outbreak beyond the camp, putting the host communities at high risk.

The latrines in the camps were built on an emergency basis when the massive Rohingya influx began in August last year. Many of the latrines are built too close to the shelters, on steep slopes, and close to canals and creeks, which are not easily accessible. Over 48,000 emergency pit latrines were installed, out of which an estimated 17 percent are now non-functional (Joint Response Plan Report 2018).

Is there a fix?

Finding a fix to environmental damages done to Ukhia and Teknaf before and after the Rohingya influx may prove extremely difficult, if not impossible, unless drastic measures are taken. For finding a long-term fix to this crisis, the Rohingya refugees should not be used as scapegoats. They are a people who have lost all their possessions back home in Myanmar and are struggling simply to survive in the camps. But in the past, in addition to plantation of exotic species, organised gangs allegedly in collusion with the Forest Department did severe harm to traditional garjan forest and used the Rohingya as scapegoats.

Currently what is needed is a rapid halt to the use of firewood for cooking purposes. The best alternative is bottled Liquid Petroleum Gas. As of early June, of this year, only 25,000 refugee families had been using it, informed the UNHCR energy expert Paul Quigley, who spoke to these writers on June 12, 2018. Borrowed from other mass refugee crises, it proves to be the cleanest and safest option. With its low emission rates LPG is the most efficient source of energy that is widely available in Bangladesh. “Companies supplying it are confident that they can bring 200,000 bottles in the camps,” says Paul.

The top soil in the hills with shelters is completely exposed, which should be covered as fast as possible. “We are planning to plant trees and encourage the Rohingya to grow vegetables,” says the UNHCR energy expert. The Forest Department also advises that the organisations and agencies (state and non-state) helping the Rohingya should consider making tree planting a regular activity in their efforts. “The Rohingya must be stopped from further expanding their territory into forest land,” says a top Forest Department official in Cox’s Bazar. “However, the FD is helplessly watching Rohingya trespassing.”

It is imperative to focus on neutral and specific research in the matter to be able to take the right policy decisions and actions to combat further environmental degradation.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing, and filming on environment for three decades. The writer acknowledges the contribution of Sabrina Miti Gain and Antarah Zaima Rahim in writing this report.

Most of the Bede boats in Kakalia disappears in 2018. Photo: Philip Gain

Most of the Bede boats in Kakalia disappears in 2018. Photo: Philip Gain House of a poor Bede in Torki, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

House of a poor Bede in Torki, Barishal. Photo: Philip Gain

has sold cosmetics and ornaments on foot all her life, a typical mode of work for Sandar Manta women. She has two sons who sell cosmetics and supplement their income by fishing in the Belai beel and river during monsoon.

has sold cosmetics and ornaments on foot all her life, a typical mode of work for Sandar Manta women. She has two sons who sell cosmetics and supplement their income by fishing in the Belai beel and river during monsoon.

back, things began to improve with the help of a police officer, Habibur Rahman, then a superintendent police of Dhaka and now a deputy inspector general of police.

back, things began to improve with the help of a police officer, Habibur Rahman, then a superintendent police of Dhaka and now a deputy inspector general of police.