by admin | Mar 21, 2024 | Investigations, Newspaper Report

Hills in Bandarban terraced for rubber plantation. PHOTO: Philip Gain

March 2, 2024. I am standing in the middle of a thorough ruination of nature in Madhupur sal forest in Tangail. Planted around 30 years ago, monoculture of a single tree—rubber—is being cut down in hundreds, every day. The trees are felled, sectioned into pieces, loaded on trucks, and taken away immediately to be used as fuelwood, manufacture boards, burn bricks, and more. All that is left are stumps that may also soon be uprooted to prepare for the next rotation of rubber plantation. For some years, pineapple and other crops will grow with rubber trees as companion crops.

This has been happening for the last few weeks at Santoshpur and Pirgachha rubber gardens in Madhupur sal forest. Rubber, an exotic tree, has spread around the world from the Amazon rainforest. If rubber is commercially planted for latex, generally it has to be felled after 30-35 years. A rubber tree gives latex for around 26 years; then it becomes old and unproductive, and must be removed!

Cutting down rubber trees in two of the five gardens in Tangail-Sherpur rubber zone started last year, when 9,000 trees on 55 acres in Santoshpur and 7,000 trees on 55 acres in Pirgachha gardens were felled. In each of these two gardens, 12,375 rubber saplings had been planted. This year’s target to cut unproductive rubber trees is 13,564 on 150 acres in Pirgachha and 25,900 on 150 acres in Santoshpur.

Unproductive rubber trees in Pirgachha Rubber Garden being felled in 2024. PHOTO: Philip Gain

Unproductive rubber trees in Pirgachha Rubber Garden being felled in 2024. PHOTO: Philip Gain

In Madhupur-Sherpur zone, there are five rubber gardens covering 8,128 acres of forestland managed by the state-owned Bangladesh Forest Industries Development Corporation (BFIDC), which has 14 more rubber gardens in other areas. Of these five gardens, four are in Madhupur sal forest on 7,503 acres of land.

The first rubber tree in Madhupur was planted on February 2, 1986. Then President HM Ershad flew to Madhupur in a helicopter to inaugurate a rubber plantation there. According to information from the BFIDC, since the first tree was planted almost four decades ago, a little over two million rubber saplings have been planted in the five gardens.

The Forest Department handed over the forestland to the BFIDC. The first thing BFIDC did to prepare the land for planting rubber saplings was clearing all of the natural vegetation—trees, shrubs, and undergrowth that harboured colonies of plant species, wildlife, birds, insects, bacteria—diverse forms of life.

Rubber plantation in Santoshpur preceded teak plantation, which replaced the natural forest. A local octogenarian from Mohishmara village named Hasmat Ali is a witness of the natural forest before teak was introduced in place of sal. “When I came to live here with my family 20 years before the Liberation War, this area had dense sal forest,” he recalled. “I saw tigers, bears and deer in the forest. We had to be careful to protect our cattle from tigers. Then we saw sal forest auctioned and teak planted. Then came rubber during the time of Ershad.”

The rubber tree that then President Ershad planted in 1986. PHOTO: Philip Gain

Rubber came to Madhupur following its plantation in the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). While finance for rubber plantation in the CHT came from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and others, the first rubber plantation project in Madhupur was reportedly financed by the government itself.

However, for the second rubber plantation project in Madhupur, as well as in other areas, ADB almost completed the formalities for funding. Feasibility study was done and funds almost got into the pipeline. But in the face of severe criticism from different quarters, local resistance, and continued reporting by this author in the national press, ADB ultimately backed down from funding the project. Had the second project taken off, 15,000 more acres of forestland would have been converted to rubber plantation, leading to further devastation and more conflicts with the local communities. The first rubber plantation project had already caused lots of tension between the state agencies and the locals.

Local communities robbed of land, lifeline and livelihoods

It is because of rubber plantation in Madhupur that the local communities, including the ethnic Garos, have dramatically lost their access to forest produce and grazing land for their cattle. Rubber plantations are monoculture—nothing else grows on their floors. They may look green from a distance, but they are actually green deserts devoid of wildlife. When the leaves fall in January-March, the trees look completely burnt and barren. This is just the opposite of the natural forest.

Rubber plantation does not bode well for nature considering its ecological impacts on local communities, particularly ethnic minor communities.

According to the Bangladesh Rubber Board, as of now, around 140,000 acres of land has been devoted to rubber plantation across the country. Most of this land is state-owned. Rubber plantation was introduced on a smaller scale during Pakistan rule, but post-independence, it grew to a massive scale during the tenures of presidents Ziaur Rahman and Ershad. Owners of the rubber gardens include state agencies such as BFIDC, Bangladesh Rubber Board, and CHT Development Board, tea gardens, Bangladesh Tea Association, and private owners.

According to the Bangladesh Rubber Board, as of now, around 140,000 acres of land has been devoted to rubber plantation across the country. Most of this land is state-owned. Rubber plantation was introduced on a smaller scale during Pakistan rule, but post-independence, it grew to a massive scale during the tenures of presidents Ziaur Rahman and Ershad. Owners of the rubber gardens include state agencies such as BFIDC, Bangladesh Rubber Board, and CHT Development Board, tea gardens, Bangladesh Tea Association, and private owners.

The most concerning and politically ill-motivated rubber plantation took place in the CHT region under private ownership on land much of which is customary to the Indigenous people in the region.

‘Caoutchouc’, a Native word for rubber tree, which means ‘the wood that weeps’. PHOTO: Philip Gain

Vast areas of rubber gardens in Lama, Naikhognchhari, Bandarban Sadar and Alikadam upazilas of Bandarban district under private ownership has caused massive ecological disaster in the hills. According to district administration sources, around 45,000 acres of public land has been leased for commercial rubber production and horticulture in the district. The size of an individual plot is 25 acres. A government document provides a list of 1,635 individuals, proprietors and companies who have received plots for rubber planting and horticulture in these four upazilas. The leases were granted between 1980 and 1996. The list is an exposé of serious anomalies and a sinister government strategy. Of the 1,635 individuals, proprietors, and companies, only 32 are members of Indigenous communities. The majority of the leaseholders are Bangalees from other districts.

“Rubber plantation requires clearing of natural forest,” says Goutam Dewan, chairman of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Citizens’ Committee. “Overall, rubber has not just been successful in the CHT; it has caused massive disaster for ecology and Indigenous communities. It has been a factor behind the eviction of many Indigenous people from their customary land that they traditionally used for jhum cultivation and production of other crops.”

Sources involved with the management of tea gardens say rubber plantation on land leased for tea production has not proven profitable. Now that the trees are mature, the fate of the land hangs in the balance.

Rubber, a colonial project

Rubber latex is indeed an amazing natural substance that we get from rubber trees. Rubber is a native species to the Amazon rainforest. The tree and its latex were unknown to Europe and Asia until Christopher Columbus brought it to Europe after his second voyage in 1493. Columbus called it caoutchouc, which means “the wood that weeps.” In Asia, the British colonists brought rubber to Sri Lanka first, then to Malaya and gradually it spread to other countries, including Bangladesh. Asia now reportedly produces most of the world’s natural rubber.

Aging Pirgachha Rubber Garden in 2018. PHOTO: Philip Gain

There was a time when humans could not think of life without goods made from natural rubber. Think of aeroplanes—could they take off in 1903 without wheels made of rubber? Most other vehicles required rubber. Despite the invention of synthetic rubber in 1931, natural rubber still remains in use in vehicles and indeed in thousands of other goods. All these rubber products have made our life easy and comfortable. It is undoubtedly a source of wealth that has brought prosperity to man. At some point, economies in Europe and North America were dependent on Brazilian rubber.

However, what is good for making man rich can be the cause of death to hundreds of other plants and animal species, including birds.

Natives of South America used to obtain milky latex from rubber trees by making incisions in the bark. Rubber has been in use for thousands of years in Latin America, dating back to as early as 1600 BCE. There was a “rubber people’ during Olmec civilisation that lived in Mexico from around 1500 BCE to 400 BCE.

The Europeans went around the world, precisely to the Americas, in search of El Dorado (gold city) and minerals. They found some gold and silver by plundering cities and demolishing native civilisations. But they found more precious things—plants—rubber being the foremost among them. The Europeans and the colonists have benefited most from the exploitation of South America in particular. The colonialism may have ended, but the economic pillage has not and rubber still continues to give prosperity to the well-off in exchange for a very high ecological damage and miseries to the Indigenous people in particular.

Rubber trees in Shontoshpur Rubber Garden felled, March 2024. PHOTO: Philip Gain

Rubber, be it in the CHT, Madhupur or in the tea gardens, may bring some economic benefits to the state and private entrepreneurs, but in general it has not been beneficial to the people who once used these lands. Worse, rubber trees have depleted resources wherever they have been planted. Imagine the first rotation of all rubber trees which will have to be cut down in the next one decade or so, and presumably in most places rubber saplings will be planted again. This means what were forest patches three to four decades ago will disappear forever. Natural rubber thus becomes a death sentence to natural forests. There are indeed alternatives to natural rubber, and our strategy should be not to expand it any further. The government can also think of replacing rubber with native plants wherever possible.

Probin Chisim in Madhupur and Sylvester Tudu, an SEHD staff, assisted in the collation of some information from the field.

Philip Gain is researcher and director at the Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

News Link: thedailystar.net | New Clip

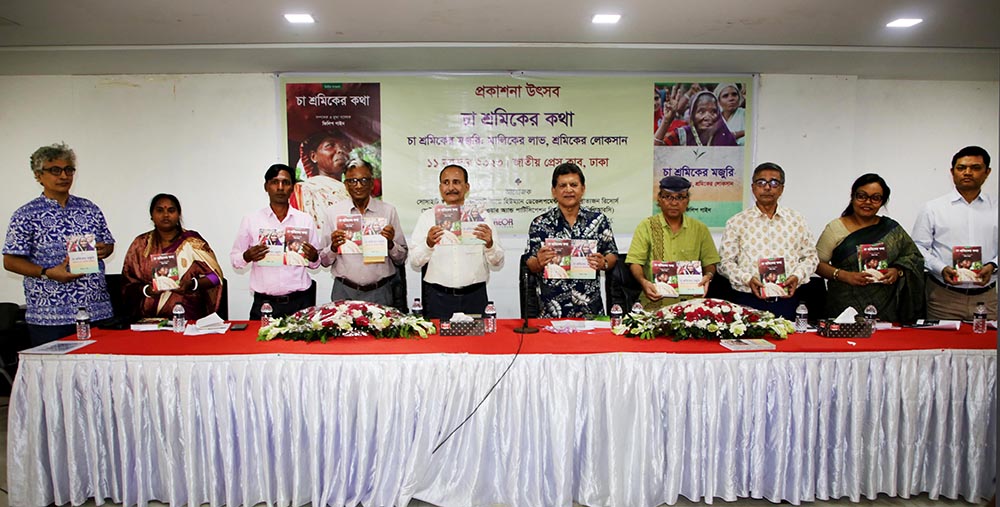

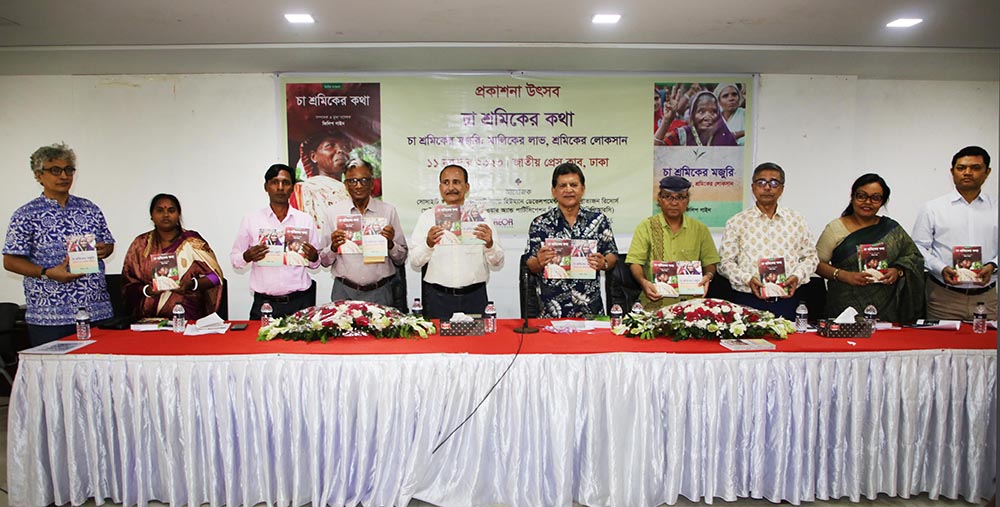

by admin | Nov 24, 2023 | Press Reports

The story of tea plantation workers of Bangladesh is one of captivity, deprivation and exploitation that has no end. Descendants of the indentured labour force, they remain tied to the tea gardens. Most of them are non- Bangalee, lower caste Hindu, Adivasis, Bihari Muslims, and their ethnic composition is unique.

Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) has been closely following the tea workers and the tea industry for two decades now. Its research, investigation and visual documentation have resulted in volumes of publications, investigative reports and three documentary films.

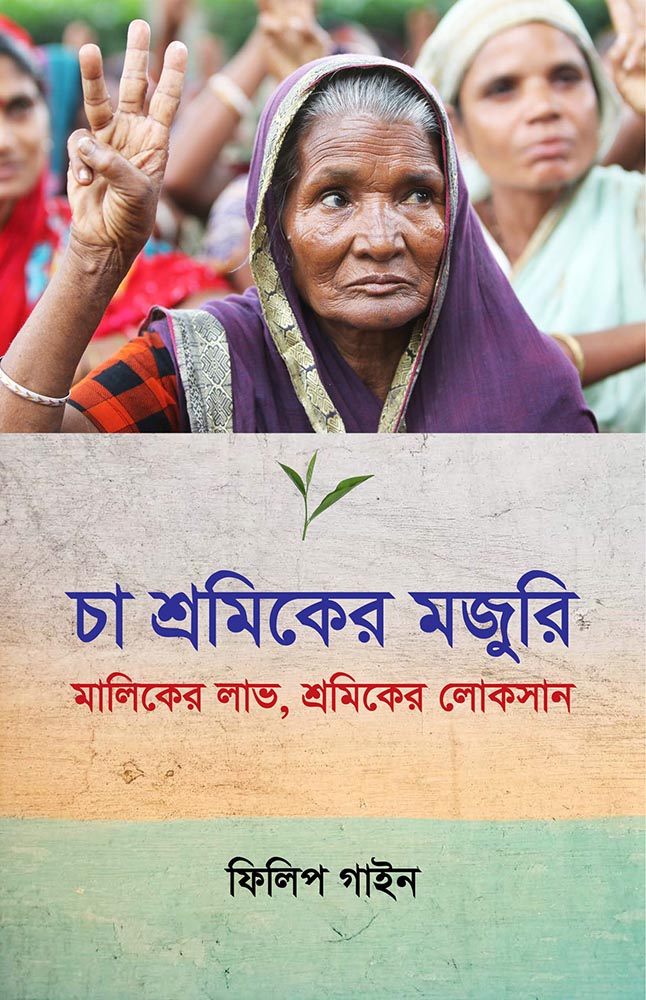

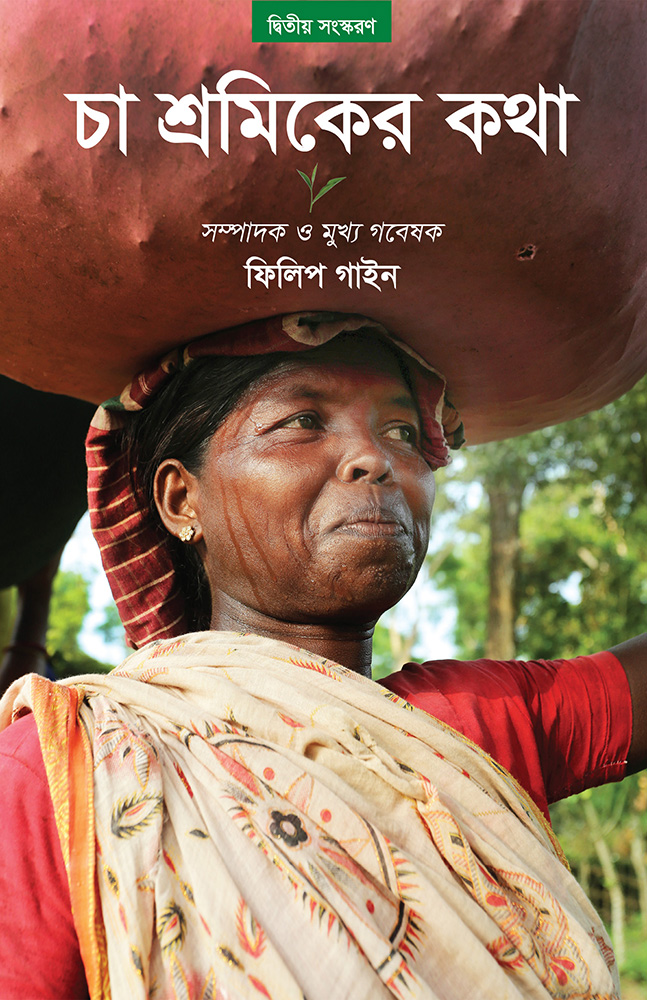

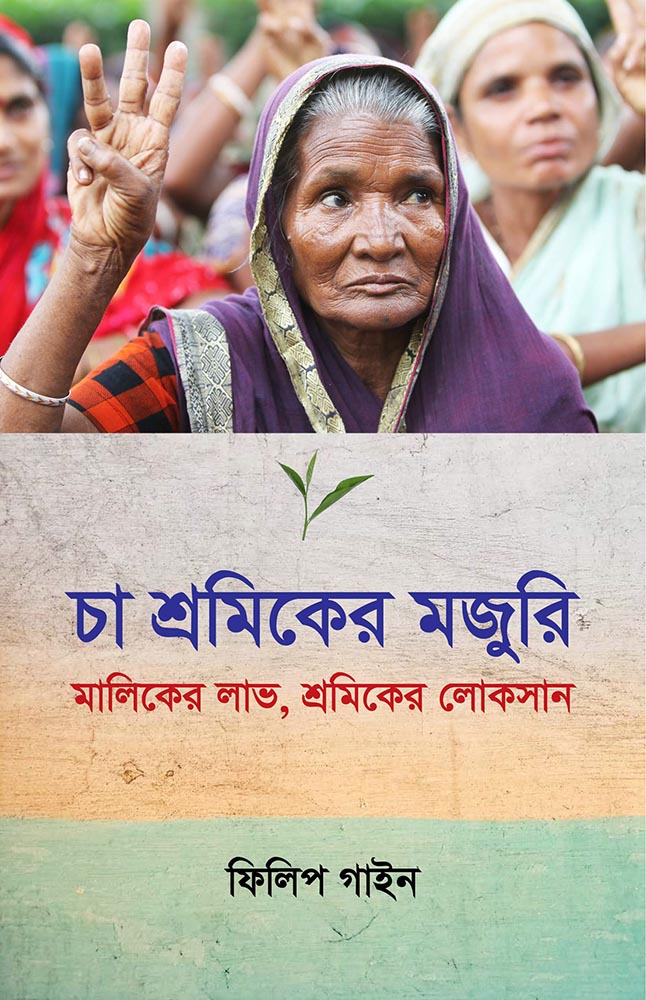

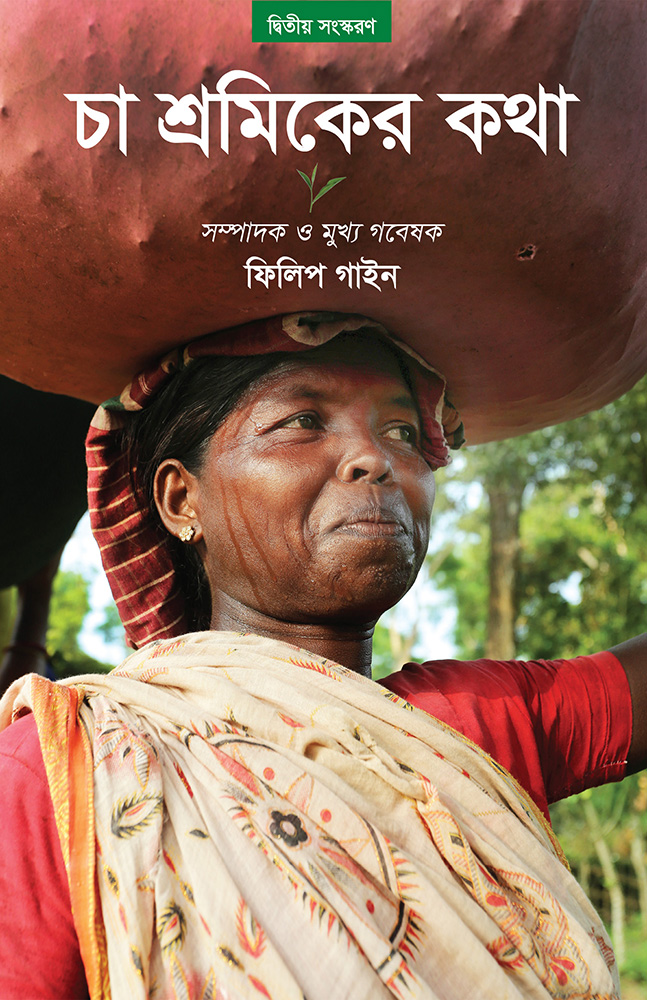

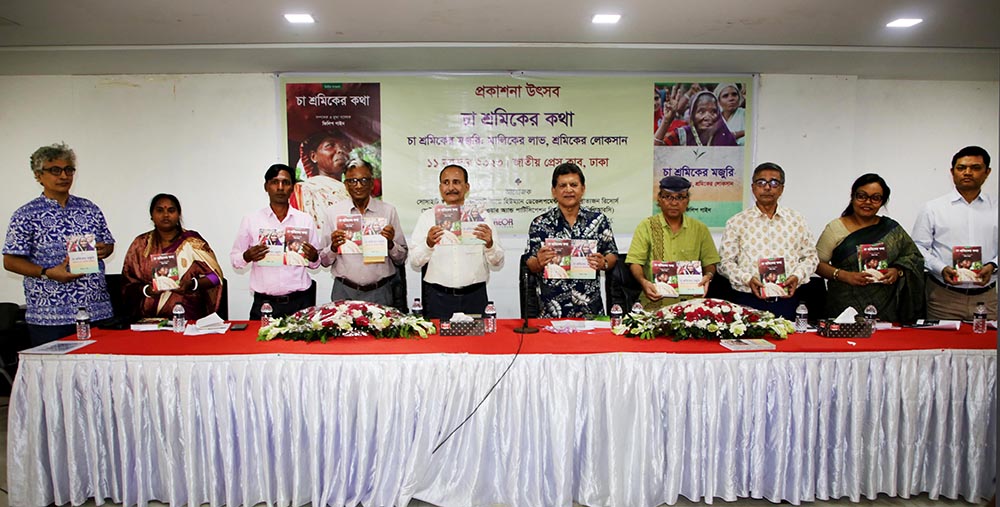

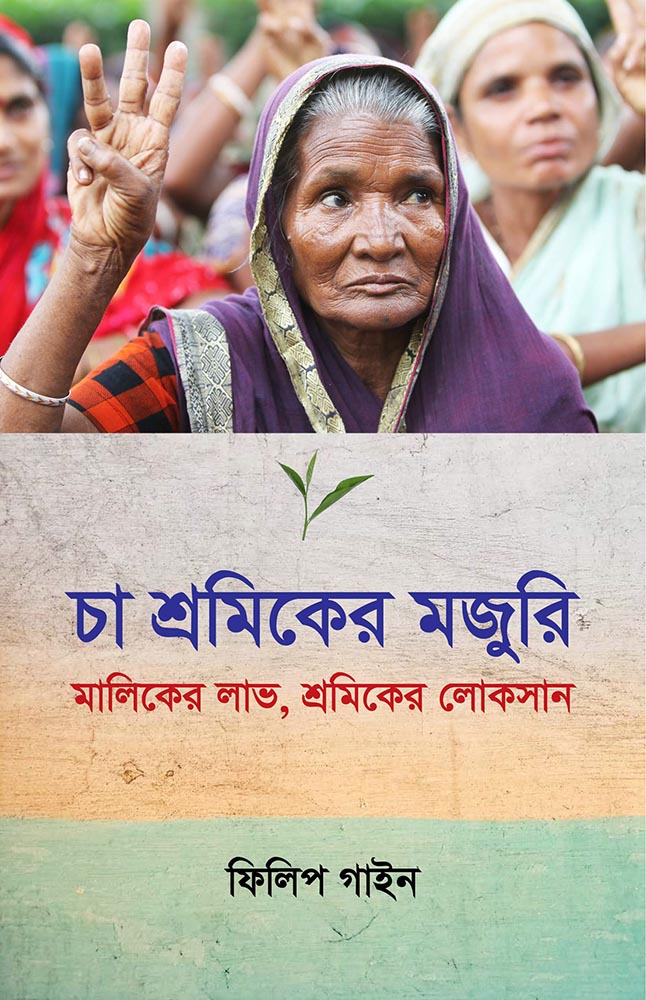

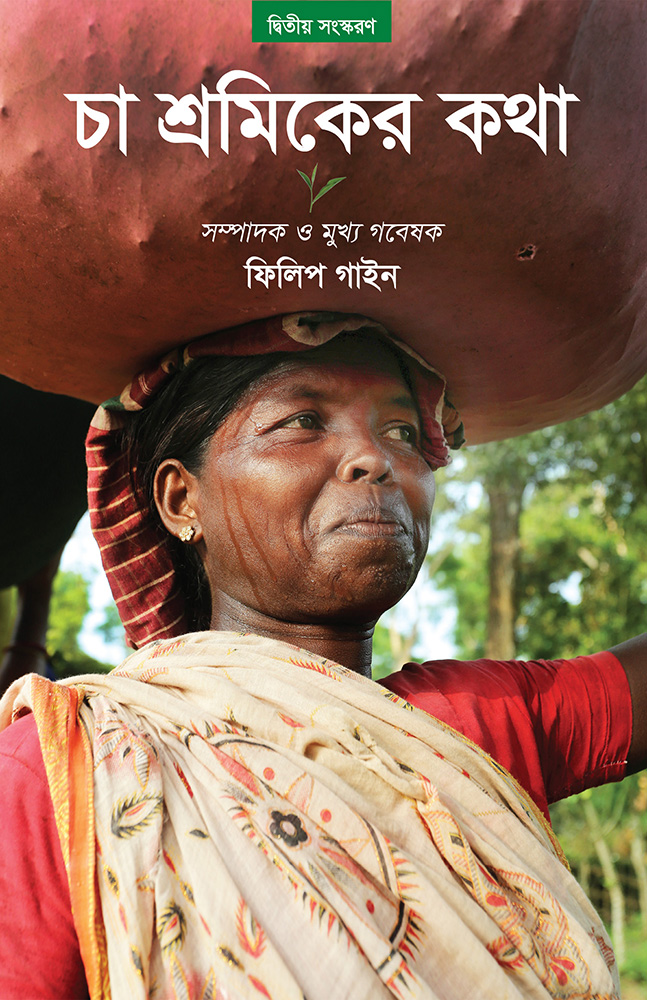

Its latest two books—Cha Sramiker Katha (The Story of the Tea Workers) edited by the writer and Cha Sramiker Mojuri: Maliker Labh, Sramiker Loksan (Wages of Tea Workers: Owners Win, Workers Lose) authored by the writer—were launched on 11 November 2023. While Cha Sramiker Katha is about the overall condition of the tea workers and the tea industry of Bangladesh, the other book concentrates on the tea workers’ wages and their unprecedented 19-day strike in August 2022 for a daily cash pay of BDT 300.

A group of tea workers including their top leaders traveled to Dhaka to attend the book launch ceremony and narrated their ordeals. A panel of economists, academics, and trade union leaders spoke strongly in favour of the tea workers. They concurred with messages that the books transpire and added their insights.

“Soon after the release of the second edition of Cha Sramiker Katha in 2022, an unprecedented 19-day strike appeared as an upheaval in the tea gardens. The strike came to end only after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina intervened and fixed the daily cash wage of workers at BDT 170, a rise from BDT 120. Although this increase did not fulfill the tea workers demand of BDT 300 in daily cash pay, the tea workers accepted it and went back to their work. Cha Sramiker Mojuri: Maliker Labh, Sramiker Loksan reviews and analyzes the events leading up to and after this unprecedented strike,” said Philip Gain, author and editor of the books and director of SEHD.

Fair wage is always the most pertinent issue and concern of the tea workers. “It is at the incitement of the owners of the tea gardens that increase of wage fell much short of what we demanded,” said Nripen Paul, the acting general secretary of Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU), the lone trade union in the tea industry. It is also the largest trade union in Bangladesh.

“We are deprived of our legitimate benefits including legal entitlements and protection,” added Sreemoti Bauri, vice president of Juri Vally of BCSU, one of the seven valleys in the tea growing districts.

The second book on workers’ wage and unprecedent strike of August 2022 that brought the tea industry to a standstill elaborately discusses the wage issues of the tea workers. In this book, the author explains how the owners’ calculation of daily wage of a worker that amounts to more than BDT 500 (USD 4.5) is seriously flawed. Benefits that the labour legislation allows to be added to the cash pay is less than BDT 300 (USD 2.7).

that brought the tea industry to a standstill elaborately discusses the wage issues of the tea workers. In this book, the author explains how the owners’ calculation of daily wage of a worker that amounts to more than BDT 500 (USD 4.5) is seriously flawed. Benefits that the labour legislation allows to be added to the cash pay is less than BDT 300 (USD 2.7).

This wage is around half of what an agricultural worker in Bangladesh gets and lot less than what lowest grade workers in other sectors get.

“The employers unjustly calculate the wages. They ignore the labour law in their calculation,” said Barrister Jyotirmoy Barua, a lawyer practicing in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh. “This attitude of the employers must change.”

On the minimum wage issue, Professor M.M. Akash, Chairman of Bureau of Economic Research (BER) of Dhaka University said, “Whenever it comes to increase tea workers’ wage, the owners say it is not possible. It is an eyewash.” He directed a question to the owners, “Why, you big companies, are taking over the tea gardens if you are not making good profits? If you do not make profit, why would you invest in the tea industry?”

“Tea workers’ job requires hard work. So, they should be paid enough so that they are able to nourish themselves adequately to be strong enough to work for eight hours. This major issue has to be taken into account while fixing their minimum wage,” Prof. Akash added.

“An audit of profit and loss of each tea garden must be carried out and made public before the owners claim ‘we are unable to pay more than this’. Because their luxurious lifestyle is telling something else,” remarked the editor of United News of Bangladesh (UNB), Mr. Farid Hossain.

Prof. Akash also pointed out how the poor economic status of the tea workers affects their fate. “If the workers had been financially well-off their 19-day strike would have lasted longer and workers could secure BDT 300 instead of BDT 170. Unfortunately, they are the ‘poorest among the poor’.”

Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman, a senior economist and chair of the book launch, talked on how important it is to pay just wages to the tea workers. “We are dreaming of turning Bangladesh into a middle-income country. To see that dream come true, we must free our policy-sphere,” said Dr. Rahman. “We cannot become middle-income country with cheap labour such as the tea workers.”

Slashing of tea workers’ arrear is another facet of deprivation alongside their unjust wage. After prime minister fixed their daily cash pay at BDT 170, they were supposed to receive around BDT 30,000 in arrear for 20 months. But each got BDT 11,000. “Such a big slash has been possible because of maneuvering of the employers and failure of the union leaders in the tea sector,” Prof. Akash observed.

“The tea workers do not have much liberty to choose their work independently outside the garden. To try that they have to leave their houses inside the plantation, which they cannot afford because the country outside the tea gardens is unknown to them and they are completely landless,” remarked Prof. Akash. “All these factors compel them to remain tied to the tea gardens at least to secure a place to live. This condition restricts them from competing for jobs with others outside the plantation.”

Barrister Barua echoed this land rights issue in his discussion: “If owners follow Section 32 of labour law diligently, then why do they not pay heed to the benefits provided by Fifth Schedule of the Labour Rules 2015? Law cannot be used only to the employers’ convenience. The industry will develop in the right direction only when owners will consider workers as assets, not just the gardens.”

Barrister Barua echoed this land rights issue in his discussion: “If owners follow Section 32 of labour law diligently, then why do they not pay heed to the benefits provided by Fifth Schedule of the Labour Rules 2015? Law cannot be used only to the employers’ convenience. The industry will develop in the right direction only when owners will consider workers as assets, not just the gardens.”

“Two books that are launched today are encyclopedic for journalists,” observed Mr. Farid Hossain. “While exploitation and hardships of the tea workers are documented in these books, some of their success stories are also highlighted. Our journalists should also focus and report such human-interest stories of tea workers.”

On the significance of struggle of the tea workers in the field, Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman said, “When the fight in field is joined by the fight with knowledge at the national level, the voice of the tea workers gets stronger. And I think with the books launched today, we have set the stage for such a collaboration. So, let us leave this publication ceremony with a feeling of strength.”

“The books launched have unveiled the tea workers situation,” said Tapan Datta, a life-long labour leader and adviser to BCSU since 1970. “These publications are another struggle like that of tea workers. It is for SEHD that tea workers’ land rights issues have come to the fore.”

Among others who spoke at the book launch included Prof. Tanzimuddin Khan and Prof. Sanjida Akhter of Dhaka University; Dhona Bauri, BCSU leader; and Abdullah Kafee of CPB.

Link: Dhaka Courier, SEHD, 24 Nov. 2023

by admin | Nov 11, 2023 | Main Reports, News & Updates

The story of tea plantation workers of Bangladesh is one of captivity, deprivation and exploitation that has no end. Descendants of the indentured labour force, they remain tied to the tea gardens. Most of them are non-Bangalee, lower caste Hindu, Adivasis, Bihari Muslims, and their ethnic composition is unique.

Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) has been closely following the tea workers and the tea industry for two decades now. Its research, investigation and visual documentation have resulted in volumes of publications, investigative reports and three documentary films.

Its latest two books—Cha Sramiker Katha (The Story of the Tea Workers) edited by the writer and Cha Sramiker Mojuri: Maliker Labh, Sramiker Loksan (Wages of Tea Workers: Owners Win, Workers Lose) authored by the writer—were launched on 11 November 2023. While Cha Sramiker Katha is about the overall condition of the tea workers and the tea industry of Bangladesh, the other book concentrates on the tea workers’ wages and their unprecedented 19-day strike in August 2022 for a daily cash pay of BDT 300.

A group of tea workers including their top leaders traveled to Dhaka to attend the book launch ceremony and narrated their ordeals. A panel of economists, academics, and trade union leaders spoke strongly in favour of the tea workers. They concurred with messages that the books transpire and added their insights.

“Soon after the release of the second edition of Cha Sramiker Katha in 2022, an unprecedented 19-day strike appeared as an upheaval in the tea gardens. The strike came to end only after Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina intervened and fixed the daily cash wage of workers at BDT 170, a rise from BDT 120. Although this increase did not fulfill the tea workers demand of BDT 300 in daily cash pay, the tea workers accepted it and went back to their work. Cha Sramiker Mojuri: Maliker Labh, Sramiker Loksan reviews and analyzes the events leading up to and after this unprecedented strike,” said Philip Gain, author and editor of the books and director of SEHD.

Fair wage is always the most pertinent issue and concern of the tea workers. “It is at the incitement of the owners of the tea gardens that increase of wage fell much short of what we demanded,” said Nripen Paul, the acting general secretary of Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU), the lone trade union in the tea industry. It is also the largest trade union in Bangladesh.

“We are deprived of our legitimate benefits including legal entitlements and protection,” added Sreemoti Bauri, vice president of Juri Vally of BCSU, one of the seven valleys in the tea growing districts.

The second book on workers’ wage and unprecedent strike of August 2022 that brought the tea industry to a standstill elaborately discusses the wage issues of the tea workers. In this book, the author explains how the owners’ calculation of daily wage of a worker that amounts to more than BDT 500 (USD 4.5) is seriously flawed. Benefits that the labour legislation allows to be added to the cash pay is less than BDT 300 (USD 2.7).

This wage is around half of what an agricultural worker in Bangladesh gets and lot less than what lowest grade workers in other sectors get.

“The employers unjustly calculate the wages. They ignore the labour law in their calculation,” said Barrister Jyotirmoy Barua, a lawyer practicing in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh. “This attitude of the employers must change.”

On the minimum wage issue, Professor M.M. Akash, Chairman of Bureau of Economic Research (BER) of Dhaka University said, “Whenever it comes to increase tea workers’ wage, the owners say it is not possible. It is an eyewash.” He directed a question to the owners, “Why, you big companies, are taking over the tea gardens if you are not making good profits? If you do not make profit, why would you invest in the tea industry?”

“Tea workers’ job requires hard work. So, they should be paid enough so that they are able to nourish themselves adequately to be strong enough to work for eight hours. This major issue has to be taken into account while fixing their minimum wage,” Prof. Akash added.

“An audit of profit and loss of each tea garden must be carried out and made public before the owners claim ‘we are unable to pay more than this’. Because their luxurious lifestyle is telling something else,” remarked the editor of United News of Bangladesh (UNB), Mr. Farid Hossain.

Prof. Akash also pointed out how the poor economic status of the tea workers affects their fate. “If the workers had been financially well-off their 19-day strike would have lasted longer and workers could secure BDT 300 instead of BDT 170. Unfortunately, they are the ‘poorest among the poor’.”

Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman, a senior economist and chair of the book launch, talked on how important it is to pay just wages to the tea workers. “We are dreaming of turning Bangladesh into a middle-income country. To see that dream come true, we must free our policy-sphere,” said Dr. Rahman. “We cannot become middle-income country with cheap labour such as the tea workers.”

Slashing of tea workers’ arrear is another facet of deprivation alongside their unjust wage. After prime minister fixed their daily cash pay at BDT 170, they were supposed to receive around BDT 30,000 in arrear for 20 months. But each got BDT 11,000. “Such a big slash has been possible because of maneuvering of the employers and failure of the union leaders in the tea sector,” Prof. Akash observed.

“The tea workers do not have much liberty to choose their work independently outside the garden. To try that they have to leave their houses inside the plantation, which they cannot afford because the country outside the tea gardens is unknown to them and they are completely landless,” remarked Prof. Akash. “All these factors compel them to remain tied to the tea gardens at least to secure a place to live. This condition restricts them from competing for jobs with others outside the plantation.”

Barrister Barua echoed this land rights issue in his discussion: “If owners follow Section 32 of labour law diligently, then why do they not pay heed to the benefits provided by Fifth Schedule of the Labour Rules 2015? Law cannot be used only to the employers’ convenience. The industry will develop in the right direction only when owners will consider workers as assets, not just the gardens.”

“Two books that are launched today are encyclopedic for journalists,” observed Mr. Farid Hossain. “While exploitation and hardships of the tea workers are documented in these books, some of their success stories are also highlighted. Our journalists should also focus and report such human-interest stories of tea workers.”

On the significance of struggle of the tea workers in the field, Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman said, “When the fight in field is joined by the fight with knowledge at the national level, the voice of the tea workers gets stronger. And I think with the books launched today, we have set the stage for such a collaboration. So, let us leave this publication ceremony with a feeling of strength.”

“The books launched have unveiled the tea workers situation,” said Tapan Datta, a life-long labour leader and adviser to BCSU since 1970. “These publications are another struggle like that of tea workers. It is for SEHD that tea workers’ land rights issues have come to the fore.”

Among others who spoke at the book launch included Prof. Tanzimuddin Khan and Prof. Sanjida Akhter of Dhaka University; Dhona Bauri, BCSU leader; and Abdullah Kafee of CPB. by Fahmida Afroze Nadia with Philip Gain

by admin | Nov 11, 2023 | Press Reports

বাংলাদেশে চা শ্রমিকের অধিকাংশই বাঙালি নন, নিম্নবর্ণের হিন্দু, বিহারি মুসলমান ও বিভিন্ন জাতিগোষ্ঠীর মানুষ। সাসাইটি ফর এনভায়রনমেন্ট অ্যান্ড হিউম্যান ডেভেলপমেন্ট (সেড) প্রায় দুই দশক ধরে চা শ্রমিক এবং চা শিল্প নিয়ে নিবিড় গবেষণা করছে। চা শ্রমিকদের নিয়ে সেড-এর সর্বশেষ দুটি গ্রন্থ ফিলিপ গাইন সম্পাদিত চা শ্রমিকের কথা এবং — তার লেখা চা শ্রমিকের মজুরি: মালিকের লাভ, শ্রমিকের লোকসান-এর মোড়ক উন্মোচিত হয় ১১ নভেম্বর ২০২৩ ঢাকার জাতীয় প্রেসক্লাবে। এই প্রকাশনা উৎসব ও আলোচনা সভার আয়োজন করে সেড, বধাত ̈জন রিসোর্স সেন্টার (বিআরসি) এবং পাওয়ার অ্যান্ড পার্টিসিপেশন রিসার্চ সেন্টার (পিপিআরসি)।

চা শ্রমিকের কথা গ্রন্থটি মূলত চা শ্রমিকদের সার্বিক অবস্থা এবং বাংলাদেশের চা শিল্প নিয়ে। অন ̈টি এর সাথী গ্রন্থ’, চা শ্রমিকের মজুরি: মালিকের লাভ, শ্রমিকের লোকসান, যাতে সন্নিবেশিত হয়েছে চা শ্রমিকের মজুরি এবং ন্যায্য ̈ মজুরির দাবিতে আগস্ট ২০২২-এ চা শ্রমিকদের ১৯ দিনের নজিরবিহীন ধর্মঘট নিয়ে অনুসন্ধানী রিপোর্ট এবং নানা তথ ̈-উপাত্ত ও বিশ্লেষণ।

বাংলাদেশ চা শ্রমিক ইউনিয়ন (বিসিএসইউ)-এর কিছু নেতাসহ একদল চা শ্রমিক গ্রন্থের মোড়ক উন্মোচন অনুষ্ঠানে যোগ দিতে ঢাকা আসেন এবং তাদের নানা কষ্টের কথা অনুষ্ঠানে বর্ণনা করেন। অর্থনীতিবিদ, শিক্ষাবিদ, সাংবাদিক এবং ট্রেড ইউনিয়ন নেতাদের একটি প্যানেল চা শ্রমিকদের পক্ষে জোরালোভাবে ব৩ব ̈ রাখেন। তারা গ্রন্থ দু’টির সারমর্মের সাথে একমত পোষণ করেন এবং তাদের নিজ ̄^ মতামত যোগ করেন।

গ্রন্থের লেখক, সম্পাদক ও সেড-এর পরিচালক ফিলিপ গাইন তার ব৩বে ̈ বলেন, “চা শ্রমিকের কথা বইটির দ্বিতীয় সং ̄‹রণ ২০২২ সালে বের করার পরপরই চা শিল্পের ইতিহাসের এক নজিরবিহীন ধর্মঘট ঘটে চা বাগানে। এর ফলে শ্রমিকদের দৈনিক নগদ মজুরি ১২০ টাকা থেকে ১৭০ টাকা হয় প্রধানমন্ত্রীর হ ̄Íক্ষেপে। এ মজুরি যথেষ্ট না হলেও চা শ্রমিকরা তা মেনে নিয়ে কাজে যোগ দেন। এই নজিরবিহীন ধর্মঘটের আগে-পরে মজুরি বৃদ্ধি নিয়ে যেসব ঘটনা ঘটতে থাকে সেসবের পর্যালোচনা ও বিশ্লেষণ নিয়ে চা শ্রমিকের মজুরি: মালিকের লাভ, শ্রমিকের লোকসান বইটি।”

New LinK: PDF

by admin | Oct 24, 2023 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | The Daily Star

Tea workers striking in August 2022, demanding a daily wage of Tk 300. PHOTO: PHILIP GAIN

The Minimum Wage Board, which was initiated in October 2019, finally published the gazette on tea workers’ wages on August 10. It is a shame that the wage board completely failed in framing and presenting acceptable recommendations on the tea workers’ wage structure. Ultimately, the prime minister made a move and fixed the wage of daily-rated tea workers at Tk 170 per day for A-class gardens, Tk 169 for B-class and Tk 168 for C-class gardens.

But why did the wage board take so long to formalise the wage structure and publish a gazette, despite the prime minister’s decision going into effect on August 2022?

The tea workers’ wage board struggled to ensure consent of the workers’ representative on the board, who actually resigned and did not approve of the acts of the wage board. The representative accepted the PM’s decision about the wages, but there are a few important issues that they did not approve while the board was completing its formalities. Regarding those matters, the Minimum Wage Board (excluding the tea workers’ representative) submitted to what the tea garden owners wanted.

“Alas, to the great disappointment of BCSU and the tea workers, the wage board’s gazette says that fixing the wages of tea workers will no longer be a negotiation between BTA and BCSU. These bodies can make decisions only regarding benefits and productivity every two years, on a consensus basis. So, it is presumed that, from now on, the Minimum Wage Board will fix the wages every five years, and that the wages will increase at a rate of five percent over basic wages/salaries, according to Section 111(5) of the amended Labour Rules 2015.”

The first important issue that disappointed the tea workers and their union was an abrupt change in a central point of the negotiation between the owners’ apex body, Bangladesh Tea Association (BTA), and the tea workers’ union, the Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU). Traditionally, BTA and BCSU have signed a labour agreement every two years, through which they fix wages and agree on other benefits. The Minimum Wage Board has been an irregular presence in the tea industry and has been formed three times so far to fix the tea workers’ wages. Its role seemed insignificant because the wages used to be set based on labour agreements signed between the BTA and BCSU. The last labour agreement expired on December 31, 2020, and no agreements were signed for the 2021-2022 period or the ongoing period. The anomalies in the wage board and the arrogance of BTA led the PM to intervene in setting the labour legislation.

Alas, to the great disappointment of BCSU and the tea workers, the wage board’s gazette says that fixing the wages of tea workers will no longer be a negotiation between BTA and BCSU. These bodies can make decisions only regarding benefits and productivity every two years, on a consensus basis. So, it is presumed that, from now on, the Minimum Wage Board will fix the wages every five years, and that the wages will increase at a rate of five percent over basic wages/salaries, according to Section 111(5) of the amended Labour Rules 2015.

This was an abrupt change, made at the wish of BTA, in the best interest of the employers, and to the great disappointment and loss of the workers. The change was reportedly proposed by BTA’s representative on the wage board, which Rambhajan Kairi (representing BCSU) rejected outright. Kairi’s argument was that such a change should have been discussed at length with BCSU and the tea workers. Cornered and disappointed, he resigned from the wage board claiming that the other members (including the chairman) had always sided with BTA. BCSU Vice President Panjkaj Kando, who replaced Rambhajan Kairi, attended one meeting before resigning on the same grounds.

The tea workers – the majority of whom are non-Bangalee, mainly Indigenous or low-caste Hindus – are tied to the tea gardens. Unlike workers in other industries, tea workers get rations at a subsidised price and some fringe benefits includinig housing, very basic health care, and free primary education. All the fringe benefits plus Tk 170 (the current daily wage of a tea worker) amounts to less than Tk 300, say labour leaders and workers. This, however, is calculated to be Tk 540 by BTA.

“A yearly increment of five percent is a very small amount and unacceptable to us,” says Kairi, former general secretary of BCSU. While he was on the Minimum Wage Board, he protested the owners’ intention to not negotiate the wage issue with BCSU. “Now, we see the Minimum Wage Board has submitted to the owners’ wishes. This goes against the long-time custom in tea gardens,” adds Kairi.

The owners not only follow the labour legislations in governing tea workers, they also follow dastur or customs that have existed in the tea gardens for a long time. The Minimum Wage Board, in its March 2010 gazette, clearly spelled out that “Cha Sramik Union in the tea garden industry sector and Bangladesh Cha Sangsad [BTA] representing the owners’ side will take decisions on productivity and other issues in addition to wages, on consensus basis, every two years after discussion according to the established custom in the tea industry.” Rambhajan Kairi and many others want this custom to prevail.

“But the August 10 gazette clearly shows that the Minimum Wage Board has imposed the owners’ wishes,” says Tapan Datta, a senior trade union leader and chief adviser to BCSU. “Because crucial decisions have been taken in the absence of the tea workers’ representative. They have actually been ignored and excluded.”

An important addition to the wages is festival bonus. In an MoU signed between BTA and BCSU in May 2023, the owners agreed to pay a festival bonus equivalent to 52 days of wages. The employers started paying festival bonuses from Durga Puja last year at this rate. The wage board has trimmed the festival bonus amount down to 47 days of wages, which is the bonus that workers had been getting before the last Durga Puja.

A lasting concern for the tea workers has been the issue of gratuity, which no worker has ever received. It has always been their demand that they are given gratuity according to the labour law. Instead, they receive a so-called pension upon retirement. This was determined to be Tk 250 a week, from January 1, 2021, and used to be Tk 150 per week before that, and only Tk 20 in 2008. BTA agreed to pay gratuity in the labour agreement signed for the 2017-2018 period with BCSU. But the employers backed out from their commitment and no worker received gratuity.

In the meantime, an amendment was made to Section 28(3) of the labour law in 2018 that exempts tea garden owners from paying gratuity. What the labour agreement signed for 2019-2020 stated was that gratuity would be paid according to the Bangladesh Labour (Amendment) Act, 2013. Labour leaders allege that the owners influenced the amendment. Now, the wage board has brought the issue into the wage structure and has stated that gratuity will only be for the staff, and that the workers will get pensions in place of gratuity, according to dastur.

But the pension that tea workers get upon retirement is much smaller than the gratuity amount, a grave injustice the hapless tea workers face. The owners’ argument for not paying gratuity is that a worker’s family does not vacate the house given to them upon retirement and that they are replaced by a family member. This is a clever way of avoiding gratuity payments, and demonstrates how the tea workers remain a captive labour force, whose forefathers arrived as indentured labourers to the tea plantations.

This situation must change. The tea workers and their communities, tied to the labour lines for five generations, must be treated as dignified people. The government has a pioneering role to play in ending the discrimination of labour legislations and practices.

An overlooked issue in the tea gardens is workers’ access to shares in the company’s profits. The owners of the tea gardens have never shared profit with tea workers. Now, the Minimum Wage Board has replicated the profit-sharing arrangement in the RMG sector (0.03 percent of sales proceeds) in the tea industry. But this is a very small amount, as 0.03 percent of total sales would be Tk 3,000 for every Tk 1 crore in sales. Secondly, workers’ participation in the company’s profit is subject to the formulation of a law and rules regarding the creation of a fund and publication of a gazette. It remains to be seen when the government will formulate the law and rules to create such a fund.

What can the tea workers and their lone union do at this critical time? The central union leaders of BCSU wanted the wage structure amended in the aforementioned areas. There is perhaps no other issue more important for them to press for than eliminating the discrimination of the wage structure and the labour legislations, as well as work on their negotiation capabilities (in facing the government and owners) for their legitimate rights.

Philip Gain is a researcher and director at the Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

News Link: thedailystar.net

Unproductive rubber trees in Pirgachha Rubber Garden being felled in 2024. PHOTO: Philip Gain

Unproductive rubber trees in Pirgachha Rubber Garden being felled in 2024. PHOTO: Philip Gain

According to the Bangladesh Rubber Board, as of now, around 140,000 acres of land has been devoted to rubber plantation across the country. Most of this land is state-owned. Rubber plantation was introduced on a smaller scale during Pakistan rule, but post-independence, it grew to a massive scale during the tenures of presidents Ziaur Rahman and Ershad. Owners of the rubber gardens include state agencies such as BFIDC, Bangladesh Rubber Board, and CHT Development Board, tea gardens, Bangladesh Tea Association, and private owners.

According to the Bangladesh Rubber Board, as of now, around 140,000 acres of land has been devoted to rubber plantation across the country. Most of this land is state-owned. Rubber plantation was introduced on a smaller scale during Pakistan rule, but post-independence, it grew to a massive scale during the tenures of presidents Ziaur Rahman and Ershad. Owners of the rubber gardens include state agencies such as BFIDC, Bangladesh Rubber Board, and CHT Development Board, tea gardens, Bangladesh Tea Association, and private owners.

that brought the tea industry to a standstill elaborately discusses the wage issues of the tea workers. In this book, the author explains how the owners’ calculation of daily wage of a worker that amounts to more than BDT 500 (USD 4.5) is seriously flawed. Benefits that the labour legislation allows to be added to the cash pay is less than BDT 300 (USD 2.7).

that brought the tea industry to a standstill elaborately discusses the wage issues of the tea workers. In this book, the author explains how the owners’ calculation of daily wage of a worker that amounts to more than BDT 500 (USD 4.5) is seriously flawed. Benefits that the labour legislation allows to be added to the cash pay is less than BDT 300 (USD 2.7). Barrister Barua echoed this land rights issue in his discussion: “If owners follow Section 32 of labour law diligently, then why do they not pay heed to the benefits provided by Fifth Schedule of the Labour Rules 2015? Law cannot be used only to the employers’ convenience. The industry will develop in the right direction only when owners will consider workers as assets, not just the gardens.”

Barrister Barua echoed this land rights issue in his discussion: “If owners follow Section 32 of labour law diligently, then why do they not pay heed to the benefits provided by Fifth Schedule of the Labour Rules 2015? Law cannot be used only to the employers’ convenience. The industry will develop in the right direction only when owners will consider workers as assets, not just the gardens.”