by admin | Jun 30, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | News Link

PHOTO: Mariusz Kluzniak/Flickr

Election of Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU) on June 24 was a joyous occasion for tea workers. BCSU happens to be the largest trade union in Bangladesh. And it is the only union for the 97,646 voters who are all registered workers in 161 tea gardens in Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chattogram and Rangamati Hill District. The recent election was the third time since 1948 that the impoverished tea workers had voted for their leaders.

largest trade union in Bangladesh. And it is the only union for the 97,646 voters who are all registered workers in 161 tea gardens in Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chattogram and Rangamati Hill District. The recent election was the third time since 1948 that the impoverished tea workers had voted for their leaders.

The first time they were allowed to vote by secret ballot was in 2008. At the time the daily pay of a tea worker was only Tk 32.50. The second election took place on August 10, 2014 when the daily pay had risen to Tk 65. In both elections, Rambhajan Kairi and Makhonlal Karmokar’s panels had won landslide victories. To no one’s surprise the results this time were the same.

Like in the past two elections, the Department of Labour (DL)—a state agency—conducted the election with an election commission headed by Shib Nath Roy, Director General (additional secretary) of DL under the Ministry of Labour and Employment. And the elections were carried out very well.

Tea workers seemed to be in high spirit on election day. Nearly 97 percent of voters showed up to vote and had no problem electing their candidates of panchayets, seven valley committees and the central committee of BCSU.

The central committee of BCSU is composed of 35 members—eight directly elected (president’s and general secretary’s panels) by voters, 22 presidents, vice-presidents, secretaries and organising secretary (only of Balishira Valley) from seven valleys (two from Balisira considering its large size compared to others), and five nominated by the losing panels of president (three) and secretary (two).

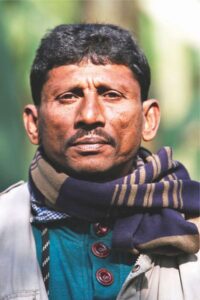

Rambhajan Kairi, elected general secretary for the third time, is happy about the elections. He was at the forefront of a youth-led campaign against Rajendraprasad Bunarjee and allegedly a central committee of his choice who controlled BCSU and its central office located in the Labour House from 1970 to 2006. No democratic elections were held during this time. “The tea workers have voted three times in BCSU and in support of our ongoing struggle for rights,” said Kairi.

Why is the government in a trade union election?

The Labour Law of 2006 considers the tea industry as a group of establishments and allows tea workers to unionise only at the national level. To form a union in the tea industry, 30 percent of the total workers must be members. Now that all registered workers have been made members of the lone union, it is unlikely for there to be a second trade union in the tea industry should the current situation persist.

What is most appalling is that BCSU remains isolated from unions, federations or confederations outside the tea industry.

“There is no precedence in recent history of the government conducting an election of a trade union in any other industry with funding support,” said Tapan Dutta, president of Trade Union Center in Chattogram and a close associate with BCSU.

Rambhajan Kairi, the winner has his contention: “The government has conducted our elections because we still have not developed our capacity to conduct elections of such a large union.”

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed, a trade union expert and Executive Director of Bangladesh Institute of Law and Labour Studies (BILS) believes that given the conflicting situation in the tea gardens, the government may come forward to assist. “But I do not know if the government has conducted election of a trade union in any other industry with funding support,” frowns Ahmed. He suggests that only one union for the entire tea industry is not desirable. The labour law should allow formation of trade unions in at least the valley level, if not at garden level. The 161 tea garden (excluding the ones in the north Bengal) are split into seven valleys.

The larger issue of the tea workers: deprivation

The larger issue beyond elections of BCSU is the deprivation of tea workers that must end. The tea industry is an industry where no tea worker gets an appointment letter and no gratuity upon retirement or end of job. Unlike other industrial workers, tea workers get no casual leave. The single most significant issue of deprivation is “unjust” wages—Tk 85 per day.

The deprivation of tea workers for four generations has deep roots. The majority of them, non-locals, belong to as many as 80 communities. The British companies brought them from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens of Sylhet region. The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens that begun more than 150 years ago. According to one account, in the early years, a third of tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to difficult working and living conditions.

To the majority of people in Bangladesh, they thus remain invisible. They sometimes treat them as aliens and are therefore indifferent about their plights and rights as equal citizens. These provide the perfect conditions for owners of tea gardens to continue exploiting them.

The state and people of the majority communities have a responsibility towards tea workers. There are allegations from different sources that state agencies and law makers are not thinking and doing enough to end the discrimination in the labour law against tea workers and are maintaining the status quo by not-implementing the labour law.

On the cultural front, tea communities, excluded and disconnected, have lost their original languages in most parts as well as their culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. They deserve special attention from the state, besides equal treatment, which go far beyond a well-managed election like the one we saw on June 24.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on tea workers and the tea industry for more than a decade. The writer acknowledges the contribution of Rabiullah in writing this article.

by admin | Jun 8, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | News Link

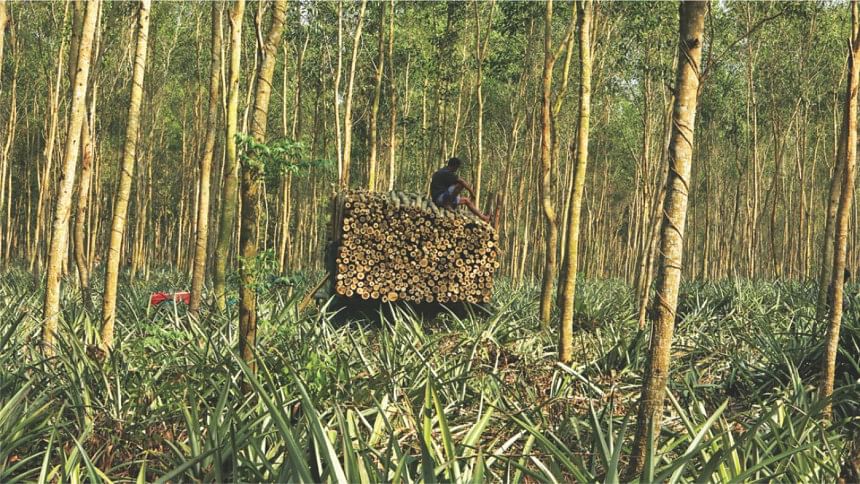

Rubber plantation in place of sal forest. Photo: Philip Gain

Sicilia Snal, aged 25 in 2006, was shot when she went to collect firewood in the forest near her village. Sicilia is a Garo woman of Uttar Rasulpur, in Madhupur sal forest area. It was early in the morning of August 21, 2006, that Sicilia went to collect firewood with a few other Garo women. On their way back, they put down their loads to take rest for a while. All of a sudden, to their great surprise, the forest guards fired shots from their guns. Sicilia was hit. She fell to the ground, unconscious and bleeding. Terrified all but one woman fled.

Then other villagers came to her rescue. She was immediately taken to Mymensingh Medical Hospital where she had a crude surgery and her gall bladder, plastered with many pellets, was removed. Some pellets remained in her kidney and around 100 pellets in the back of her body and hands—she has to live with these for the rest of her life.

Eleven years have passed since she was shot. The local Garos staged some protests and small humanitarian aid came to her family immediately after the assault. A case was also filed on her behalf. But the forest guards who fired the gun shots were never brought to justice. Nobody seriously moved with the case either.

Sicillia and other Garo women still go to the forests, their ancestral land, to collect firewood. Asked about the state of the case filed on her behalf Sicilia says in great frustration, “I know nothing about the case.” She believes the Forest Department and the Forest Guards are immune from legal action.

Before and after Sicilia was shot, a few killings and abuse of forestland in Madhupur made headlines in national and international newspapers. Notable among them was the killing of Piren Snal that left the Garos in terror. On January 3, 2004, the Garos organised a peaceful rally to evince their disdain against the so-called eco-park within the Madhupur National Park. While the Forest Department was desperate about fencing an area with concrete walls to demarcate the eco-park, the Garos saw it as a threat and an attempt to restrict their free movement in the forest they consider as their ancestral land.

The forest guards, with support from other security agencies, fired shots from their guns to disperse the rally. Hit by bullets, Piren Snal, a 28-year Garo youth from Joynagachha village, died on the spot. Utpol Nokrek, an 18-year youth then, was shot from the back, right into the spine that sent him to a wheel chair for the rest of his life.

The Madhupur sal forest is just one hotspot of abuses inflicted on forest villagers. The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) is a vast forest landscape of Bangladesh that demonstrates serious abuses of all kinds done to the forest and forest people. Let me give the example of a small Chak forest village in Bandarban—and how the Chaks were eventually evicted from it.

It was in December 2008 that I first went to Badurjhiri, in Naikhongchhari upazila in Bandarban, which was, at the time, inhabited by 15 Chak families. Distinct from other ethnic communities in Bangladesh, this tiny Chak community lived for centuries in remote forest villages, satisfied with their traditional jum agriculture. Guided by a group of Chak men, we walked three and a half hours from Baishari Chak paras (hamlets) in Naikhongchhari upazila to reach Badurjhiri.

There had always been fears about invasion by Bangalees attracted to the land’s forest produce and encroachment of rubber and tobacco plantations by them, but Badurjhiri remained vibrant nonetheless, with crops that came from jum, pigs, fowls, and a rich variety of vegetables.

Going back to Badurjhiri in December 2010 was something of a shock. The rubber cultivators had expanded their boundaries towards Badurjhiri. The Chak men and women we walked with explained how the jungle continued to be cleared for rubber cultivation. In 2008, when we were passing through Amrajhiri, the jungle was being cleared in preparation for fresh rubber plantation. The nearby hills in the east, west, and south still had coverage of native forests. Two years later, we found out that the entire area had been cleared.

Commercial tobacco cultivation in Naikhhongchhari that is destructive for the forest. Photos: Philip Gain

Rubber cultivation was fast taking over their village, and the Chaks were afraid of what awaited them. They had witnessed how rubber plantation, among other reasons, had forced the Chaks of the neighbouring Longodujhiri (Khal) Chak Para to abandon their village. A Thoai Ching Chak, a villager, remarked, “If rubber cultivation spreads close to our village, we will surely be evicted.” He perhaps did not imagine that his fear would come true so soon.

They had to desert their village in April 2013.

Before the eviction, every time I would go to Badurjhiri, a group of Chak men and women would accompany me, but when I went back in 2013, they refused to go there. They told me horrific stories of attacks on them. On the night of March 19, 2013 the whole village was attacked by armed assailants in the dead of the night. For hours they stabbed and beat men and women, vandalised houses, slaughtered chickens (and loaded them in sacks), and looted belongings.

After the deadly attack, young girls and the wounded immediately left Badurjhiri. In April, almost all of the Chaks of Badurjhiri deserted the village. The 15 Chak families of Badurjhiri took shelter in four Chak villages in Baishari. They still live there.

Abuse, ill treatment and underlying factors

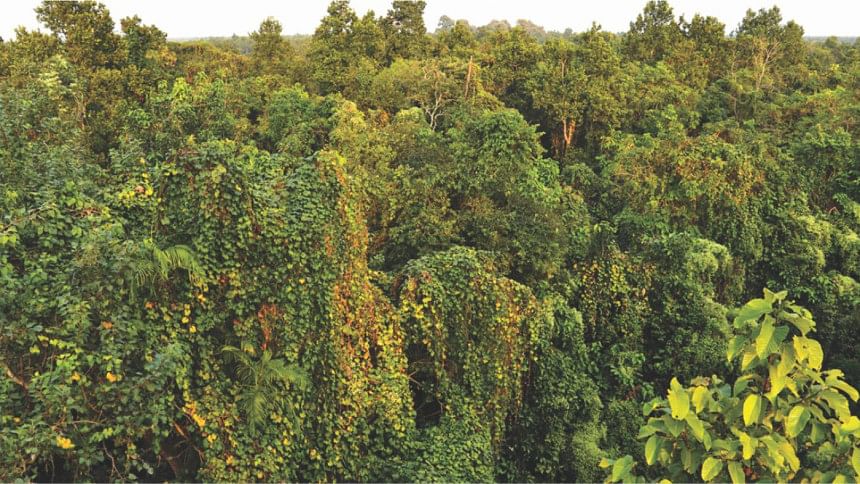

Abuses and ill treatment of the forest people—in Madhupur, Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), Khasi hamlets or other sal forest areas—are mere symptoms of underlying factors that have brought the forest to ruin. Officially, 18 percent of the country (2.6 million hectares) is public forestland—landmass recorded as forestland when the Forest Act of 1927 came into being. But in reality, approximately 6 percent is said to be covered by forests. This includes the mangroves and plantations covering 403,458 hectares since 1873. According to the Forest Department estimate, it now controls only 10.3 percent of the land surface (Forest Department 2001).

The largest category of forests in Bangladesh is reserved forests, which include the Sundarbans in the southwest (601,700ha), and forests in the CHT region in the southeast (322,331ha) and the Madhupur tracts in the north-central region (17,107ha). A much smaller category is the protected forests. Privately owned forests are another category, which range from plantations to those that are wholly owned by private individuals or companies. The last category of forests is unclassed state forests (USF), most of which is in the CHT.

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

The relationship between people living in and around the forests is intimate—reciprocal and spiritual. The life and culture of the forest communities centre around the forests and the forest ecology. Their sustenance is dependent on the forest and therefore they do what they can to protect it. They are the “children of the forest” in the truest sense. To them civilisation and culture are inexorably connected with land, ecology and nature. It wasn’t too long ago that most of the indigenous peoples of Bangladesh lived in forests. Many factors, including actions taken by the state, have led to the massive destruction of the forest, and dispossessed forest communities of their land.

Reservation of the forests, beginning in the days of British colonial rule, has greatly curbed the rights of different indigenous communities to the land and the forests. In the CHT, about a quarter of the land was declared reserved forest during the British colonial era, severely limiting access of the indigenous communities to the land that had been their commons for centuries. Reservation of forest continues to date.

The local communities consider the expansion of the reserved forests as an immoral act. It dispossesses them of the means of their livelihood, and does immense harm to biodiversity and to knowledge production about medicinal plants of the local indigenous communities. The expansion of reserved forests, mainly for plantations, financed by international financial institutions (IFIs) and donors, has further muddied the waters when it comes to questions about land and ecology in the CHT, Madhupur and elsewhere.

Monoculture plantation has been the single biggest threat to the native forests in the hills as well as in the plains, affecting the life and livelihood of the forest-dependent communities. Plantations in Bangladesh include pulpwood (in the CHT), rubber, agroforestry, woodlot (for the production of fuelwood), teak, pine, etc. It is mainly the Forest Department and Bangladesh Forest Industries Development Corporation (BFIDC) that carry out the plantations on public forestland, mostly in the CHT, Chittagong, Cox’s Bazar, Sylhet and the sal forests. The IFIs—ADB and World Bank—funded most of these recent plantations.

The negative multiplier effects of manmade forest or plantations are quite similar around the globe. This is best illustrated in the words of Patricia Marchak (in her book, Logging the Globe, 1995), a Canadian scholar: “Plantations are monoculture, and the lack of biodiversity is of concern. They typically have sparse canopies and so do not protect the land; they cause air temperatures to rise, and they deplete, rather than increase, the water-table. They are generally exotic to regions. While the initial planting may be free of natural pests and diseases, that situation will not last, and plantation regions may not be in the position to combat scourges yet to arrive.”

When we look at the plantations on our public forestland, Patricia Marchak’s contention begins to make sense. It is possible to plant trees but it is impossible to create a forest. Hundreds of species of trees and bushes and a large number of other vegetable species grow on the forest floor. The knowledge of the forest-dwelling communities, their traditions, culture, history, education are all part of the forest. And now, all this has been seriously affected.

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

The displacement of human communities is another consequence of a plantation economy. In the CHT, pulpwood and other industrial plantations (including rubber and tobacco) have displaced human communities (jumias in particular) who have lived in the forests for centuries. The eviction of the Chaks from Badurjhiri and Longodujhiri in Bandarban is a clear pointer to the effects of plantation on forest villagers.

Ecological damage caused by rubber plantation and the so-called social or community forestry on public forestland is another concern. Although a rubber plantation looks green, it is a desert for other plant species, birds and wildlife. It brings in some cash for the government and private entrepreneurs, and misery and trouble for the local communities.

Vast expanses of banana, pineapple, papaya and spice plantations that we see in Madhupur sal forest can have far-reaching effects on the soil, seeds, wildlife, and human health. The trade in chemical pesticides, fertilisers and hormones related to it is huge.

Plantations provide ample ground to land grabbers to illegally convert the forestland to agricultural land. And it is the rich, the influential and the outsiders who encroach upon forestlands in collusion with government agencies and political forces. Banana plantations, illegally established on a massive scale on the forestland in Madhupur, are an example of how the plantation economy gives outsiders an opportunity to encroach upon public forestland. It is primarily the rich and the politically influential who control banana cultivation and benefit from it.

Aside from the plantations carried out with foreign funds (both loans and grants), state-sponsored and aid-dependent ‘development’ initiatives from the Pakistan era have had devastating consequences for the land and forests in the CHT. During the Pakistan regime, two development interventions of the state, Karnaphuli Paper Mill (KPM) and the Kaptai Hydroelectric Project, were a matter of “national pride”. But the projects caused unprecedented ecological damage from the start and posed the biggest threat to the indigenous peoples of the hills and their economic, aesthetic, and political life.

Is there a fix?

It is in the best interests of the nation and its people that whatever is left of the native forests in Bangladesh is protected from the onslaught brought about by monoculture plantation and human greed. Given all the damage done to the forests since colonial times, a natural fix is difficult to come by. However, if there is any hope of protecting what little is left, all actors, particularly the government agencies and donors, must recognise the underlying factors that have ruined the forest(s), especially the plantation economy and development initiatives taking place on forestland.

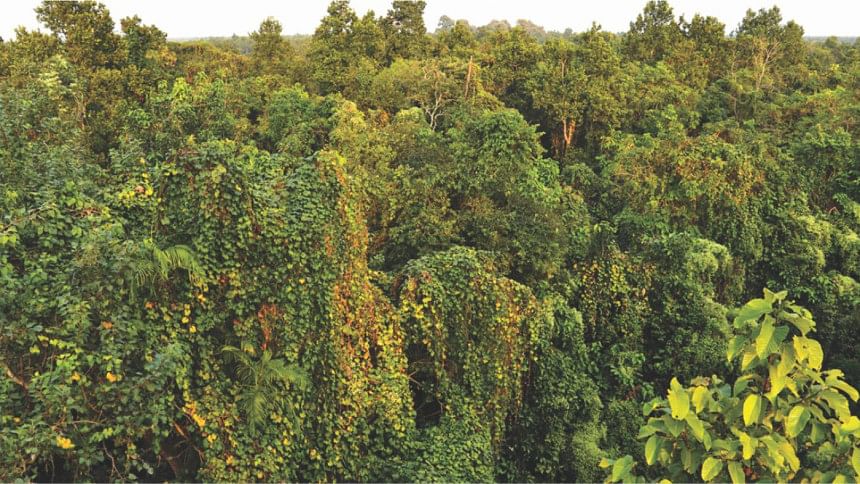

The surviving forest patches of Bangladesh are still so rich that the seeds and coppices would easily regenerate a degraded forest. A mature sal tree in any sal forest patch, for example, produces thousands of seeds in a season alone which can be planted for its expansion.

Banana plantations that have ruined much of sal forests to the core. Photo: Philip Gain

The sal forests in Madhupur and elsewhere provide an environment conducive for hundreds of other species of plants and life forms to grow. Professor Salar Khan (late) who guided the National Herbarium for many years requested the Forest Department not to plant exotic species to create monoculture in a place home to hundreds of native species. He tried to convince the department that the consequence of single species plantation is the destruction of genetic resources that the sal forest had sustained. He was ignored. He consistently requested the Forest Department to protect the remaining sal forests and replant wherever possible. ADB’s withdrawal from funding any forestry project in Bangladesh since 2007 is evidence that Professor Salar Khan was right. The World Bank’s funding in the forestry sector is reportedly limited.

In the CHT a hill left untouched for some years becomes green with myriad native species. In an abandoned jum plot in the CHT, countless native species appear and spread throughout the plot only in a few years. But a hill, planted with teak, pulpwood or other industrial monoculture, is likely to be ruined. Plantation is a manmade disaster that needs to be prevented in any forestland that has a chance to regenerate. However, “complex” or mixed plantation can be an option in areas that are truly degraded. Even in that situation there is no need for exotic species; there is plenty of local species.

Wrongs done to the forests and forest-dwelling communities need to be righted if justice is to be done. For that to happen, both forest and forest-dependent communities must be given protection. We should not forget the warning of Chandi Prashad Bhatt who said: “Unless we find a framework in which forests and people can live together, one or the other will be destroyed.”

Philip Gain is a researcher and the director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Madhupur sal forest, the Chittagong Hill Tracts and forest people since 1986.

by admin | May 11, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | The Daily Star

The nonagenarian remembers what it was like to be a Garo before the forest dramatically disappeared from Madhupur and Christianity took over.

Dinesh Nokrek, in his nineties, is a Garo kamal in Dharati village of Madhupur forest in Tangail. In Garo society, kamal signifies a priest in the traditional Garo religion of Sangsarek—a vanishing tradition, as almost all Garo people have by now converted to Christianity. Nokrek, who often likes to announce that he is a hundred years old, is a kabiraj (village doctor) as well. He has a strange device, sim-ma-nia, to diagnose and treat diseases including cancer. It remains hung on the mud wall inside his living-cum-dining room, which is stuffed with everything from sacks of grain to utensils.

Nokrek has no hesitation in announcing that he is a very happy man in his conjugal life with his 70-year-old second wife Monikkha Rema, whom he married seven years ago. He spotted Rema, a widow in Sandhakura village of Sherpur district, and married her following the sangsarek ritual.

Happy in a truly remote village on the western edge of the Madhupur sal forest, which evinces no mark of the sal tree any more, Nokrek has a very interesting life story to tell, of a forest that has dramatically disappeared from Madhupur [and elsewhere].

Father to five sons and three daughters—all from his first marriage to wife Palshi Dalbot, who passed away 10 years ago—Nokrek says he was born in Gypsy Pahar (pahar meaning hills), two kilometres east of Kamalapur Railway Station in Dhaka, which he remembers was a low-lying land. “The British filled the low-lying area with mud,” recollects Nokrek “and developed Kamalapur Rail Station.”

At least 80 Garo families lived at Gypsy Pahar, recalls Nokrek. The area was then covered with sal forest and there were many tigers and bears around, reminisces Nokrek excitedly. “Jum (slash-and-burn) cultivation was the primary agricultural practice in Gypsy Pahar, under the jurisdiction of the king of Natore,” he recalls. “We also practised limited plough agriculture.”

The hunting of pigs with spears was common, “but we were not allowed to kill deer and peacocks,” says Nokrek.

In Gypsy Pahar, all Garo families were sangsarek in contrast to today’s Garo society, in which Christianity is the dominant faith.

“The worst experiences in Gypsy Pahar were the encounters with tigers that were everyday events,” exclaims Nokrek. There is hardly anyone in Madhupur who knows that the Garo families came to the villages of Madhupur forest from distant locations such as today’s Kamalapur in Dhaka. This carries a significant message—the Garo are a hill and forest dwelling people. The sal forest, now miserably fragmented, extended up to Comilla and the traces of the Garo people around Kamalapur—before the station came into existence—is a significant mark in the history of migration of the Garo.

Dinesh Nokrek does not recall the exact year when his father moved out of Gypsy Pahar and came to Nalia in Ghatail. Actually, all Garo families in Gypsy Pahar, according to Nokrek, moved back north over a number of years. One landmark for Nokrek’s family is the big riot of 1964.

“My father, along with many other Mandis, moved to Nalia in Ghatiail 10 to 15 years before the big riot,” Dinesh explains. “I was very young then.”

Nalia was a kind of transit area before his father moved to Madhupur, then a dense forest with sparse Garo houses. “We lived hardly eight years in Nalia and some years in Mohishmari before moving to Madhupur, where we first landed in Dokhola and then went to Bagadoba,” Nokrek says.

“We left different forest areas mainly due to tigers and bears. But upon coming to Madhupur, we found the forest even more tiger-infested,” Nokrek recounts. “We used to encounter tigers every day and one year I killed two of them with a gun.”

It is from Bagadoba that Nokrek went to his wife’s house. Unlike other young men, it was quite a hard deal for him to settle in his wife’s family.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

In the young Nokrek’s case, his parents had delayed serving dinner to their son. Hungry, Nokrek sat to eat late in the evening and it was then that one of the captors entered the dining room and jumped him from behind.

“Manjok (captured)!” shouted the capturer to the others waiting outside. “Ribarembo (come quickly)!” The story still excites Nokrek. “Six strong men captured me. Each of them held different parts of my body and I was helpless,” says Nokrek, smiling wistfully. As they were marching with their hapless capture, they shouted “Man-ba-jok (We are coming with the son-in-law)!” From Bagadoba, Nokrek was taken to the neighbouring Dublakuri village in Jamalpur district.

Nokrek was married off soon after he was brought to the bride’s house. Such quick marriages following the traditional custom are called ‘murgichira bia’. A dinner of fowls was then served to the starving Nokrek.

Dinesh Nokrek explaining the power of sim-ma-nia. Photo: Philip Gain

Married at 28, Nokrek was not happy with his wife’s family because they were not well off. He spent the night quietly and fled to his parents’ house the next morning.

“I wanted to abandon my wife, so I stayed a year at my father’s house,” recalls Nokrek. “But then the village leaders convinced me to return to my wife’s house.” A large pig was slaughtered and a celebration followed.

With his wife, Nokrek moved back to Bagadoba from Dublakuri seven years into their marriage. They lived there till 1988, when they moved to Dharati—Nokrek’s current village.

Today, Dharati is a mixed village with 155 Garo households and 124 Bengali households. Rubber plantations flank the village on either side and banana, pineapple, ginger, turmeric and other cash crops cover the entire village. The 8,000-acre sal forest was ruthlessly cleared to plant rubber trees. Still considered a forest, the land was transferred to the Bangladesh Forest Industry Development Corporation (BFIDC) for production of rubber.

Like other Garo villages, all but Dinesh Nokrek and a few others are Christians in Dharati. In his family, only Nokrek is Sangsarek. His sons and daughters are Christians. His second wife, always smiling, pretends to be Sangsarek to make Nokrek happy. She was Christian before coming to his family. Nokrek himself is open-minded about Christianity.

Like Dinesh, most of the elderly Garo people of the forest villages in Madhupur tell stunning stories of their migrations, the celebration of Christianity in Garo villages, the destruction of the forest and the factors that underpinned various other changes. Unlike in the past, they are now settled in their villages. Yet, some move to cities in search of jobs and income. The Garo in the capital today, approximately 15 percent of its total population of around one lakh, speaks to the transformation of the Garo community, as a result of Christianity and the spread of education.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Madhupur sal forest and its people since 1986.

by admin | Apr 30, 2018 | Newspaper Report

by Philip Gain, Dhaka Tribune, April 30th, 2018

Hemlata Bauri (65) earns tk 60 for a full day’s work at Daluchhera Tea Garden in Fenchuganj upazila, Sylhet district. She is paid a daily wage, so she does not get a weekly holiday. If she opts to work on a public holiday, she only gets Tk 30 for it. For these wages, she has to reach a nirikh (daily quota) of 20 kgs of tealeaves to qualify for the daily cash payment – hard work under the heat of the midday sun in the hilly tea garden terrains of Sylhet. Bauri has been a tea worker for nearly 50 years now. She became a ‘registered worker’ many years after she joined, but she has never been issued an appointment letter, which the owner is compelled to issue according to labour law. The workers of this tea garden are not members of the Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU), the only trade union for around 160 tea gardens that have around 122,000 workers. It is also the largest trade union in the country. Daluchhera Tea Estate, one of 19 tea gardens in Sylhet district, is a small garden with 34 registered and 15 casual workers. It is a ‘C’ class garden, which means its production capacity is less than that of ‘A’ and ‘B’ class gardens. Our recent investigation shows unprecedented irregularities in wage payment at Daluchhera. The chairman of the panchayet of the tea garden, Barma Turia, informed us that “wages here was Tk30 even four years ago.” The workers of the garden demanded a pay rise when wages in other gardens increased. The workers and the owners side sat together and determined the current daily cash pay of Tk60. However, a condition was imposed of a minimum of 12 hours of work a day. Turia informed us that workers end up working around eight hours a day instead.

Such cash pay is a clear breach of written agreement between the owners’ association and BCSU.

Rambhajan Kairi, the general secretary of BCSU reaffirmed, “Paying lower wages is not just a breach of agreement between the owner and workers, but also a violation of the Labour Law. The agreement was indeed made under the rubric of Labour Law 2006.” According to this agreement, daily cash payments for ‘C’ class gardens is Tk82 and, Tk85 and Tk83 for ‘A’ and ‘B’ class gardens respectively, effective from January 2015. The condition at Daluchhera is believed to be the worst in all the 160 tea gardens in the traditional tea growing five districts—Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chittagong and the Rangamati Hill District. However, the conditions of tea workers and their communities, with a huge proportion of them generally being non-Bengali, is very different from other industrial workers in terms of their identities and access to justice as workers. The British companies, more than 150 years ago, brought these tea workers from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens in Sylhet region.

The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens.

According to one account, in the early years, a third of the tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to the tough work and living conditions. Upon arrival, these labourers received a new identity – that of coolie – and became property of the tea companies. These coolies, belonging to many ethnic identities, cleared jungles, planted and tended tea seedlings and saplings, planted shade trees, and built luxurious bungalows for tea planters. But they had their destiny tied to their huts in the “labor lines” that they built themselves.

Today, what is most concerning for the tea workers is their wages—daily or monthly.

The maximum daily cash pay for the daily rated worker in 2008 was Tk 32.50 (less than half a US$), which was raised to Tk 48.50 (US 63 cents) by the first ever minimum wage board assigned for the tea workers that went into effect from September 1, 2009. This was still a miserable pay that had severe effects on the daily life of tea workers. As a result of negotiations between the workers’ representatives and the owners mediated by the government, the daily cash pay of the tea workers was raised to Tk 69, which went into effect from June1, 2013.

The conditions of tea workers and their communities, with a huge proportion of them generally being non-Bengali, is very different from other industrial workers in terms of their identities and access to justice as workers

The current (2015) central committee of BCSU, in its latest agreement with the Bangladesh Tea Association, had been able to raise the daily cash pay to Tk 85 for A-class gardens, Tk 83 for B-class gardens and Tk 82 for C-class gardens. This new wage structure went into effect from January 2015.

It was also the first time in the history of the tea industry that workers began to get paid for weekly holidays (on Sunday).

It was also the first time that owners agreed to provide gratuity, which however, is not yet given in any garden. The excuse the owners use for such low pay is fringe benefits given to workers. The key fringe benefits include free housing and concessional rate of ration (rice/wheat) at Tk 2.00 per kg. A worker, on average, gets around seven kgs of food grains at concessional rate. The houses provided are basic. The workers are obviously very unhappy about these wages. “The current wages, Tk85 per day, are unjust. In the agreement that will be effective from January 2017, we will demand a daily cash pay of Tk230. It is still not enough, but we are demanding this in consideration of the overall situation,” says Rambhajan Kairi, who is leading on-going negotiations with the owners on behalf of the workers. “But the owners are proposing Tk95. This is very illogical and unjust. We will not accept it in any way.” “The owners are also not yet paying gratuity,” says Kairi, “which is a breach of our agreement.”

Confined to the tea gardens, tea workers are considered to modern-day slaves by many, and are one of the most vulnerable peoples of Bangladesh

Fringe benefits other than housing and rations include some allowances, attendance incentive, access to khet land for production of crop (those accessing such land have their rations slashed), medical care, provident fund, pension, etc.

The daily cash pay of a Bangladeshi tea worker is much lower than what a tea worker gets in Sri Lanka, which is around $4.5.

However, the cash pay of a tea worker in India is not a lot better than what the tea workers of Bangladesh have started to get from January 2015. Confined to the tea gardens, tea workers are considered to modern-day slaves by many, and are one of the most vulnerable peoples of Bangladesh. Into the fifth generation, they continue to remain socially excluded, low-paid, overwhelmingly illiterate, deprived and disconnected. They have also lost their original languages in most part, culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. Fearful of their future in an unknown country outside the tea gardens, the tea communities keep their voices down and stay content with the meagre amenities of life. As citizens of Bangladesh, they are free to live anywhere in the country. But the reality is that many of the members of the tea communities have never stepped out of the tea gardens.

An invisible chain keeps them tied to the tea gardens.

Social and economic exclusion, dispossession and the treatment they get from their managements and Bengali neighbours have rendered them ‘captive’ or ‘tied’ labourers. It is in this background that they deserve special attention of the state and the people of the majority community, not just equal treatment, which however, remains a far cry. Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing, filming, photographing the tea communities for more than a decade.

by admin | Apr 27, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | News Link

Hssan Ali appeared at Tangail Forest Court on January 4, 2018 to take bail in a ‘forest case’ (no. 405) that was filed in 1998 for felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

Hasan Ali and his family of two wives, three daughters and two sons, are now permanent residents of Gachhabari village of Aronkhola union in Madhupur upazila. Nearly a hundred Bengali families settled in the part of Gachhabari village that eventually came to be known as Farm Para during the Pakistan era. Gachhabari, before the Bengali moved in, was a Garo village and the area was covered with pretty deep jungle. Today that has disappeared and natural vegetation is replaced by plantation of acacia, pineapple, papaya and spices.

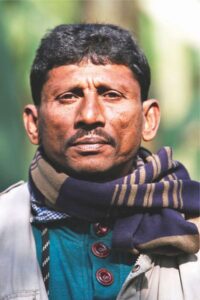

Hasan Ali. Photo: Philip Gain

Ali has been appearing before Tangail Forest Court for this particular case along with others since 1998 and waited years to see whether he is charged or not. He has appeared before the court for just one case at least 60 times, and has served jail-time for approximately 14 months for 20 other cases. Since 1990, Ali has faced around 100 forest cases—35 of them settled, but not without penalties.

Ali does not know anyone who has faced so many cases in Madhupur. “Now I am facing more than 65 forest cases. On average I go to Tangail Forest Court nearly 10 days in a month,” reports Ali. “In the past, sometimes I would go to court every work day in a given week.”

Dealing with forest cases is an expensive affair. “For each case settled I have spent ar0und Tk 60,000,” says Ali. “So far I have spent around Tk 40 lakhs.”

Yet, Hasan Ali is one of the more financially secure ones facing forest cases. Ali’s monthly family income looks good at the village standard. “But every month I spend at least Tk 20,000 on cases,” he says, “and therefore I am always in debt.”

Ali is one of the thousands facing forest cases in Madhupur forest area. But in a number of cases he is exceptional. “The allegations the Forest Department (FD) makes in the forest cases are vague or false,” claims Ali. “Some of the allegations the FD made in forest cases against me and others are based on hearsay.”

“I have never been caught red-handed,” asserts Ali. Everyone of the accused that this writer interviewed concurs with Ali—they do not flatly deny that they never got engaged in cutting trees. But they report that the massive tree felling in the Madhupur sal forest started in the early 1990s, which coincides with the advent of social forestry.

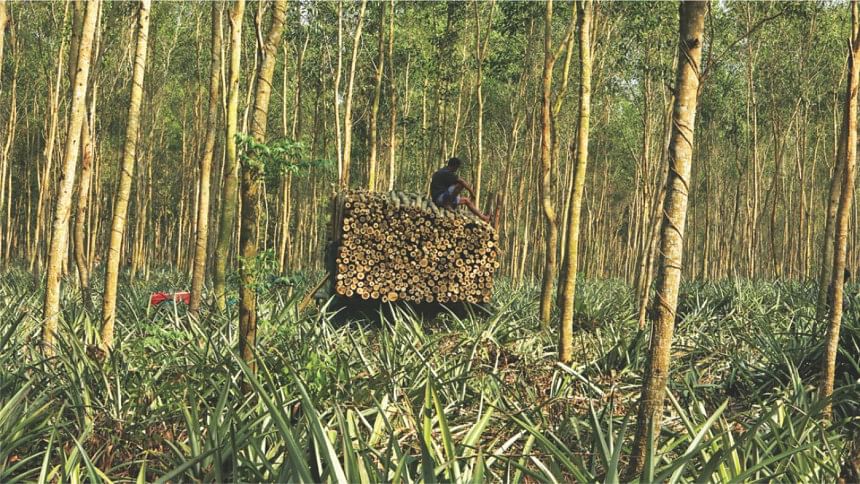

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

“It is the FD that engaged the tree-felling gangs to clear patches of sal forest. It was illegal. Then foreign trees (eucalyptus and acacia) were planted in place of sal and other local species,” alleges Ali. “We protested against such illegal deals, only to have the FD file forest cases against us.” The case in which Ali got bail on January 4, 2018 was one such case from 1998.

The act of such illicit deals came to be known as giving “line”. To set a “line”, the FD allegedly fixed an amount and allowed the wood cutters hired by “line” gangs to cut trees from certain areas.

There were locals who sometimes worked for these gangs, state the villagers. However, most of them were outsiders who were paid daily wages. “Then the same FD filed forest cases against us because we were seen felling trees, an act performed for the preparation of social forestry plantations,” says Ali.

Md Yunus Ali, who retired as Chief Conservator of Forest (CCF) on January 2017, refutes the allegation that social forestry was carried out clearing sal forest patches in many places. “Social forestry—woodlot and agroforestry—had been carried out only in places of forest land where there was no potential for regeneration of natural forest,” he argues.

Ali and others in the Madhupur forest villages, however, narrate a different story. The villagers say that little of the Madhupur sal forest survives today because of social forestry projects implemented by the Forest Department and funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Ali and others—Garo and Bengali—who have been trying to rescue themselves from the web of forest cases hardly had any forest cases filed against them before social forestry began. “None of the cases filed against me are related to natural forests,” asserts Ali.

Social forestry was supposed to help local people. “The reality is just the opposite. It has been very harmful for locals and the environment,” laments Md. Ramjan Ali of Amlitala, a village in the middle of the Madhupur sal forest.

Ramjan reports that the first forest case filed against him was in 1996, when he was a student of class nine and away from home. Shocked and angered, he could not continue his studies. Twenty-eight cases were filed against him, of which 10 have been settled and 18 are still pending. Ramjan has so far been in Tangail Jail 11 times—from one week to 29 days.

For Ramjan Ali it has been a very high-priced affair to deal with forest cases. “For each case settled,” sighs Ramjan Ali, “I have spent around Tk 1 lakh. Lately I had to spend Tk 30,000 to take bail in just one case.”

“When cases were filed against a poor wage-earner, he had no other choice but to engage in further tree-felling activities to manage cash for running cases,” explains Ramjan Ali. “The forest cases are actually traps, which are beneficial for the FD, lawyers, police and others.”

Many, unable to manage cash, have either never appeared before the court or stopped showing up completely. They go into hiding with arrest warrants issued against them.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Jitendra Nokrek (48), a farmer and day-labourer of Joloi village, is one such Garo. Accused in four forest cases, he appeared before the forest court from 1993 up to 2000. He was also put into jail five times—the durations ranging from one week to 10 days. He sold 90 decimals of his land to run cases. “Then I stopped appearing before the court,” says Nokrek, “because I could not manage cash anymore.” The police are searching for him. “I cannot sleep in my house in peace. Sometimes I hide at night in other people’s houses.” Fed up, he has also thrown away the documents of forest cases.

Niren Nokrek (54), also from Joloi, does not know how many cases are there against him. “I have heard from others that there are forest cases against me. I never showed up in the court because they are expensive and never-ending.” says Niren furtively, while talking to this writer in a tea stall.

Niren and others claim that the FD files cases without any good reason. “Sometimes they file cases against names taken from the voter list,” alleges Niren.

Anyone can be a target of forest cases

The forest cases can be filed against anyone—respected Garo social leaders, school teachers and anyone who have, at different times, protested against the ‘misdeeds’ of the Forest Department, allege villagers.

One recent example of such forest cases involves Eugin Nokrek (53) of Gaira village, a traditional Garo village right in the heart of Madhupur National Park—a village that has existed there since long before the creation of the Forest Department and the national park. In the first of two cases from 2016, he is accused of land grabbing and attempting to establish a banana plantation and in the second he is accused of stealing and smuggling trees from the forest.

Eugin Nokrek, president of Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad, the most important social organisation of the Garo and Koch of Madhupur, believes the cases have been filed against him because of his activism. “I have been leading the resistance of the adivasis of the Madhupur forest. At the center of our movement is our land rights. We want our land and forest protected. The FD files false forest cases to keep us under pressure,” responds Nokrek.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

There was one forest case against Eugin at the time of resistance against an eco-park in 2004. The case was later dismissed.

“The FD filed another case right after the visit of Shantu Larma, chairman of the CHT Regional Council, who came to Madhupur to express his solidarity with our movement,” reports Eugin. Shantu Larma visited Madhupur on September 22, 2016. The day before, Eugin claims, top-ranking local government officials accompanied Awami League’s Madhupur branch vice-chairman Yakub Ali to Eugin’s Jalchhatra office with a request to cancel Shantu Larma’s programme. “But we could not keep the request, which angered the FD and a case was filed against me,” alleges Eugin.

An FD official based in National Park Sadar (JAUS) Range of Madhupur forest, however, provides a conflicting version of events surrounding the forest cases filed against Eugin Nokrek, claiming the cases filed are well grounded. “Eugin Nokrek got a one-hectare plot of natural vegetation (sal coppices) under a co-management arrangement between the FD and the locals,” says the official. “Under such arrangement, the participants, Eugin being one of them, are supposed protect sal coppices and other species of natural vegetation. They will get a percentage of benefit for their time investment.”

He alleges that Eugin Nokrek allowed clearing a part of his plot and plantation of banana. “This is a serious offence, so we filed cases against him,” says the official who also adds that the FD wanted to amicably settle matter with Eugin Nokrek. “But he did not respond to our request and we had no alternative but to file cases.

This version that the forest official relayed to this writer does not match with the pleading made in the case document—which accuse Eugin of general tree felling.

There are many other community leaders and school teachers who are financially crushed due to forest cases. One such teacher is Nere Norbert of Gaira village, who actively participated in the resistance movement against the eco-park. The FD filed 12 cases against him between 2004 and 2008. “Nine of the cases filed against me have been settled in 14 years, at very high price—Tk 9 lakhs,” says Norbert.

Such a huge expenditure for cases has financially crippled Norbert, a father of six children. “The mental pressure for forest cases is immense,” says Norbert. “I have been falsely rendered plunderer of the very forest that we have always tried to protect.”

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

According to the Tangail Forest Court annual report from 2017, the number of forest cases pending action till December was 4,954, which in 2016 was 5,350. Of the cases pending in 2017, 2,236 had been taken into cognizance and 2,718 were under trial. The number of forest cases settled in 2017 was 626 and fresh cases filed during this year were 230.

Of 626 cases settled, 288 were settled after full court procedure. 175 people in 48 cases have been convicted, while 837 people have been acquitted in 240 cases. Cases settled without full trial and through other means were 338 and 968 accused have been acquitted in these cases.

The Forest Court in Tangail is the only court in the district to settle all forest cases. One special magistrate is assigned for this court. However, the forest court is functional only part-time—from 2:30 pm to 4:00 pm, five days a week.

The highest number of forest cases occurs in Madhupur, followed by Sakhipur, Mirzapur and Ghatail.

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), in its independent household survey in 44 villages, found 3,029 forest cases pending as of 2017.

The Bench clerk of Tangail Forest Court, Tapan Chowdhury, confirms that the forest cases filed in the court dramatically increased in 1991-1992, when natural forest patches were indiscriminately cut in favour of plantations. Most of the cases have been lingering in court.

On allegation that excessive forest cases were filed during the first decade of social forestry, Md Yunus Ali, however, says, “It is not true at all that forest cases were filed in excessive numbers during the initial stage or the first five years of social forestry.”

CFWs—’thieves’ become protectors!

The Forest Department created a troop of community forest workers widely known as CFWs to guard the forest that is on the brink of ruination. CFWs, in the eyes of the FD, were forest thieves and most of them face forest cases. The idea of turning the ‘forest thieves’ into protectors was brewed in the project, ‘Re-vegetation of Madhupur Forests through Rehabilitation of Forest Dependent Local and Ethnic Communities’ that started in July 2009. The CFWS were given incentives such as cash that came in different forms [though small] and promise of relief from forest cases. The CFWs appreciated cash pay to each of them for patrolling the forest to keep the remnants safe (!) from being stolen.

Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul, a former conservator of forest who served as DFO, Tangail and director of the USAID-funded project asserted that “Forest cases decreased significantly at my time (between 2011 to 2013) and filing of fresh forest cases in those years came down to almost nil, because crime decreased significantly.”

Hasan Ali and Ramjan Ali were two of 786 CFWs (according to the latest count). They remember Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul with gratitude. But CFWS are no more active and have stopped patrolling the forest. The prime factor is the funding for the project has stopped. “The false or fabricated forest cases against us have not been settled as promised,” complains Hasan Ali. Ramjan Ali and other victims of forest cases concur with Ali.

What Hasan Ali, Ramjan Ali and hundreds of other victims of forest cases realise is that no sympathy of one or two forest officials will help unless the systems and policies have changed and appropriate judicial measures have been taken.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Modhupur sal forest and its people since 1986.

Rabiullah, Probin Chisim and Sonjoy Kairi assisted the writer in gathering information from Tangail Forest Court.

largest trade union in Bangladesh. And it is the only union for the 97,646 voters who are all registered workers in 161 tea gardens in Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chattogram and Rangamati Hill District. The recent election was the third time since 1948 that the impoverished tea workers had voted for their leaders.

largest trade union in Bangladesh. And it is the only union for the 97,646 voters who are all registered workers in 161 tea gardens in Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chattogram and Rangamati Hill District. The recent election was the third time since 1948 that the impoverished tea workers had voted for their leaders.

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail. Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest. Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today. Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry. Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was. Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.