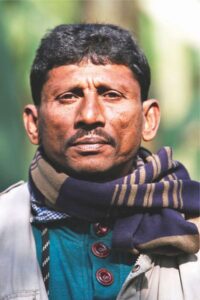

Hssan Ali appeared at Tangail Forest Court on January 4, 2018 to take bail in a ‘forest case’ (no. 405) that was filed in 1998 for felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

Hasan Ali and his family of two wives, three daughters and two sons, are now permanent residents of Gachhabari village of Aronkhola union in Madhupur upazila. Nearly a hundred Bengali families settled in the part of Gachhabari village that eventually came to be known as Farm Para during the Pakistan era. Gachhabari, before the Bengali moved in, was a Garo village and the area was covered with pretty deep jungle. Today that has disappeared and natural vegetation is replaced by plantation of acacia, pineapple, papaya and spices.

Hasan Ali. Photo: Philip Gain

Ali has been appearing before Tangail Forest Court for this particular case along with others since 1998 and waited years to see whether he is charged or not. He has appeared before the court for just one case at least 60 times, and has served jail-time for approximately 14 months for 20 other cases. Since 1990, Ali has faced around 100 forest cases—35 of them settled, but not without penalties.

Ali does not know anyone who has faced so many cases in Madhupur. “Now I am facing more than 65 forest cases. On average I go to Tangail Forest Court nearly 10 days in a month,” reports Ali. “In the past, sometimes I would go to court every work day in a given week.”

Dealing with forest cases is an expensive affair. “For each case settled I have spent ar0und Tk 60,000,” says Ali. “So far I have spent around Tk 40 lakhs.”

Yet, Hasan Ali is one of the more financially secure ones facing forest cases. Ali’s monthly family income looks good at the village standard. “But every month I spend at least Tk 20,000 on cases,” he says, “and therefore I am always in debt.”

Ali is one of the thousands facing forest cases in Madhupur forest area. But in a number of cases he is exceptional. “The allegations the Forest Department (FD) makes in the forest cases are vague or false,” claims Ali. “Some of the allegations the FD made in forest cases against me and others are based on hearsay.”

“I have never been caught red-handed,” asserts Ali. Everyone of the accused that this writer interviewed concurs with Ali—they do not flatly deny that they never got engaged in cutting trees. But they report that the massive tree felling in the Madhupur sal forest started in the early 1990s, which coincides with the advent of social forestry.

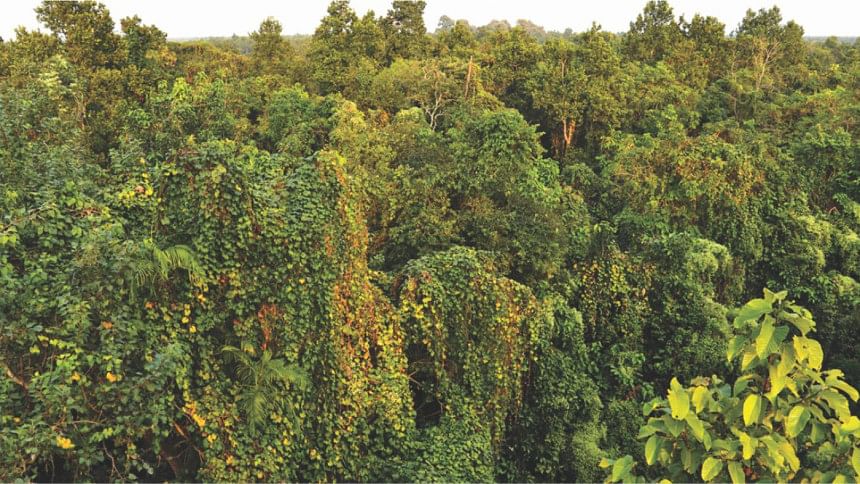

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

“It is the FD that engaged the tree-felling gangs to clear patches of sal forest. It was illegal. Then foreign trees (eucalyptus and acacia) were planted in place of sal and other local species,” alleges Ali. “We protested against such illegal deals, only to have the FD file forest cases against us.” The case in which Ali got bail on January 4, 2018 was one such case from 1998.

The act of such illicit deals came to be known as giving “line”. To set a “line”, the FD allegedly fixed an amount and allowed the wood cutters hired by “line” gangs to cut trees from certain areas.

There were locals who sometimes worked for these gangs, state the villagers. However, most of them were outsiders who were paid daily wages. “Then the same FD filed forest cases against us because we were seen felling trees, an act performed for the preparation of social forestry plantations,” says Ali.

Md Yunus Ali, who retired as Chief Conservator of Forest (CCF) on January 2017, refutes the allegation that social forestry was carried out clearing sal forest patches in many places. “Social forestry—woodlot and agroforestry—had been carried out only in places of forest land where there was no potential for regeneration of natural forest,” he argues.

Ali and others in the Madhupur forest villages, however, narrate a different story. The villagers say that little of the Madhupur sal forest survives today because of social forestry projects implemented by the Forest Department and funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Ali and others—Garo and Bengali—who have been trying to rescue themselves from the web of forest cases hardly had any forest cases filed against them before social forestry began. “None of the cases filed against me are related to natural forests,” asserts Ali.

Social forestry was supposed to help local people. “The reality is just the opposite. It has been very harmful for locals and the environment,” laments Md. Ramjan Ali of Amlitala, a village in the middle of the Madhupur sal forest.

Ramjan reports that the first forest case filed against him was in 1996, when he was a student of class nine and away from home. Shocked and angered, he could not continue his studies. Twenty-eight cases were filed against him, of which 10 have been settled and 18 are still pending. Ramjan has so far been in Tangail Jail 11 times—from one week to 29 days.

For Ramjan Ali it has been a very high-priced affair to deal with forest cases. “For each case settled,” sighs Ramjan Ali, “I have spent around Tk 1 lakh. Lately I had to spend Tk 30,000 to take bail in just one case.”

“When cases were filed against a poor wage-earner, he had no other choice but to engage in further tree-felling activities to manage cash for running cases,” explains Ramjan Ali. “The forest cases are actually traps, which are beneficial for the FD, lawyers, police and others.”

Many, unable to manage cash, have either never appeared before the court or stopped showing up completely. They go into hiding with arrest warrants issued against them.

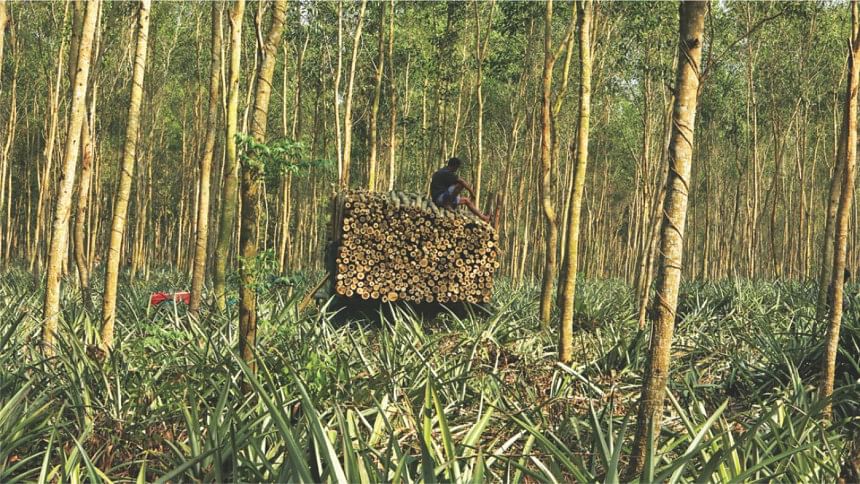

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Jitendra Nokrek (48), a farmer and day-labourer of Joloi village, is one such Garo. Accused in four forest cases, he appeared before the forest court from 1993 up to 2000. He was also put into jail five times—the durations ranging from one week to 10 days. He sold 90 decimals of his land to run cases. “Then I stopped appearing before the court,” says Nokrek, “because I could not manage cash anymore.” The police are searching for him. “I cannot sleep in my house in peace. Sometimes I hide at night in other people’s houses.” Fed up, he has also thrown away the documents of forest cases.

Niren Nokrek (54), also from Joloi, does not know how many cases are there against him. “I have heard from others that there are forest cases against me. I never showed up in the court because they are expensive and never-ending.” says Niren furtively, while talking to this writer in a tea stall.

Niren and others claim that the FD files cases without any good reason. “Sometimes they file cases against names taken from the voter list,” alleges Niren.

Anyone can be a target of forest cases

The forest cases can be filed against anyone—respected Garo social leaders, school teachers and anyone who have, at different times, protested against the ‘misdeeds’ of the Forest Department, allege villagers.

One recent example of such forest cases involves Eugin Nokrek (53) of Gaira village, a traditional Garo village right in the heart of Madhupur National Park—a village that has existed there since long before the creation of the Forest Department and the national park. In the first of two cases from 2016, he is accused of land grabbing and attempting to establish a banana plantation and in the second he is accused of stealing and smuggling trees from the forest.

Eugin Nokrek, president of Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad, the most important social organisation of the Garo and Koch of Madhupur, believes the cases have been filed against him because of his activism. “I have been leading the resistance of the adivasis of the Madhupur forest. At the center of our movement is our land rights. We want our land and forest protected. The FD files false forest cases to keep us under pressure,” responds Nokrek.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

There was one forest case against Eugin at the time of resistance against an eco-park in 2004. The case was later dismissed.

“The FD filed another case right after the visit of Shantu Larma, chairman of the CHT Regional Council, who came to Madhupur to express his solidarity with our movement,” reports Eugin. Shantu Larma visited Madhupur on September 22, 2016. The day before, Eugin claims, top-ranking local government officials accompanied Awami League’s Madhupur branch vice-chairman Yakub Ali to Eugin’s Jalchhatra office with a request to cancel Shantu Larma’s programme. “But we could not keep the request, which angered the FD and a case was filed against me,” alleges Eugin.

An FD official based in National Park Sadar (JAUS) Range of Madhupur forest, however, provides a conflicting version of events surrounding the forest cases filed against Eugin Nokrek, claiming the cases filed are well grounded. “Eugin Nokrek got a one-hectare plot of natural vegetation (sal coppices) under a co-management arrangement between the FD and the locals,” says the official. “Under such arrangement, the participants, Eugin being one of them, are supposed protect sal coppices and other species of natural vegetation. They will get a percentage of benefit for their time investment.”

He alleges that Eugin Nokrek allowed clearing a part of his plot and plantation of banana. “This is a serious offence, so we filed cases against him,” says the official who also adds that the FD wanted to amicably settle matter with Eugin Nokrek. “But he did not respond to our request and we had no alternative but to file cases.

This version that the forest official relayed to this writer does not match with the pleading made in the case document—which accuse Eugin of general tree felling.

There are many other community leaders and school teachers who are financially crushed due to forest cases. One such teacher is Nere Norbert of Gaira village, who actively participated in the resistance movement against the eco-park. The FD filed 12 cases against him between 2004 and 2008. “Nine of the cases filed against me have been settled in 14 years, at very high price—Tk 9 lakhs,” says Norbert.

Such a huge expenditure for cases has financially crippled Norbert, a father of six children. “The mental pressure for forest cases is immense,” says Norbert. “I have been falsely rendered plunderer of the very forest that we have always tried to protect.”

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

According to the Tangail Forest Court annual report from 2017, the number of forest cases pending action till December was 4,954, which in 2016 was 5,350. Of the cases pending in 2017, 2,236 had been taken into cognizance and 2,718 were under trial. The number of forest cases settled in 2017 was 626 and fresh cases filed during this year were 230.

Of 626 cases settled, 288 were settled after full court procedure. 175 people in 48 cases have been convicted, while 837 people have been acquitted in 240 cases. Cases settled without full trial and through other means were 338 and 968 accused have been acquitted in these cases.

The Forest Court in Tangail is the only court in the district to settle all forest cases. One special magistrate is assigned for this court. However, the forest court is functional only part-time—from 2:30 pm to 4:00 pm, five days a week.

The highest number of forest cases occurs in Madhupur, followed by Sakhipur, Mirzapur and Ghatail.

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), in its independent household survey in 44 villages, found 3,029 forest cases pending as of 2017.

The Bench clerk of Tangail Forest Court, Tapan Chowdhury, confirms that the forest cases filed in the court dramatically increased in 1991-1992, when natural forest patches were indiscriminately cut in favour of plantations. Most of the cases have been lingering in court.

On allegation that excessive forest cases were filed during the first decade of social forestry, Md Yunus Ali, however, says, “It is not true at all that forest cases were filed in excessive numbers during the initial stage or the first five years of social forestry.”

CFWs—’thieves’ become protectors!

The Forest Department created a troop of community forest workers widely known as CFWs to guard the forest that is on the brink of ruination. CFWs, in the eyes of the FD, were forest thieves and most of them face forest cases. The idea of turning the ‘forest thieves’ into protectors was brewed in the project, ‘Re-vegetation of Madhupur Forests through Rehabilitation of Forest Dependent Local and Ethnic Communities’ that started in July 2009. The CFWS were given incentives such as cash that came in different forms [though small] and promise of relief from forest cases. The CFWs appreciated cash pay to each of them for patrolling the forest to keep the remnants safe (!) from being stolen.

Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul, a former conservator of forest who served as DFO, Tangail and director of the USAID-funded project asserted that “Forest cases decreased significantly at my time (between 2011 to 2013) and filing of fresh forest cases in those years came down to almost nil, because crime decreased significantly.”

Hasan Ali and Ramjan Ali were two of 786 CFWs (according to the latest count). They remember Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul with gratitude. But CFWS are no more active and have stopped patrolling the forest. The prime factor is the funding for the project has stopped. “The false or fabricated forest cases against us have not been settled as promised,” complains Hasan Ali. Ramjan Ali and other victims of forest cases concur with Ali.

What Hasan Ali, Ramjan Ali and hundreds of other victims of forest cases realise is that no sympathy of one or two forest officials will help unless the systems and policies have changed and appropriate judicial measures have been taken.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Modhupur sal forest and its people since 1986.

Rabiullah, Probin Chisim and Sonjoy Kairi assisted the writer in gathering information from Tangail Forest Court.