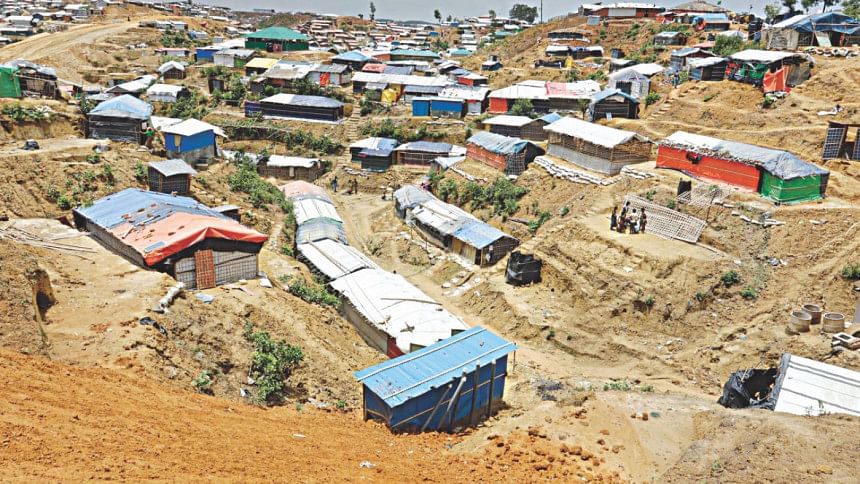

We stand in the middle of Rohingya Camp No. 18. It is in the southwest of Kutupalong Rohingya camp cluster in Ukhia upazila of Cox’s Bazar district. We are stunned. What used to be green hills months ago are completely devoid of vegetation today and covered with tens of thousands of flimsy shelters made of bamboo, polythene, and tarpaulin of different colours. There is hardly any empty space in the hills occupied by the Rohingya.

The hills in the 5,800 acres of forestland (as of early this year) have not only been stripped off of vegetation—natural or planted—they have been thoroughly downsized. Some have been levelled and many partially cut out for construction of roads. Red, sandy mud is piled here and there. The temporary shelters have been built on the terraced hills from top to bottom.

The biggest refugee camp in the world today—Kutupalong—has been split into 24 smaller camps and each camp is designated a number. Of the total 32 camps, other eight camps are scattered in Teknaf upazila.

The landscape that was once filled with songs of birds and crickets and roamed around by elephants and a myriad other wild creatures is thoroughly degraded today. Every inch is now occupied by humans. During the daytime, a low clamour can be heard everywhere and the Muslim call for prayer ring out from the mics of the mosques at intervals.

On May 19 this year, when we stood in the completely ruined forest landscape, we stopped Giasuddin, a young man from Balukhali (a village east of Camp No. 18) to hear how he as a local felt about the abrupt change in his neighbourhood.

“The entire area was jungle with acacia plantation. This is elephant territory,” says Giasuddin with confidence. “I have seen tigers, elephants, and other animals in this area. The jungle was there until Rohingya poured in.”

Monjur Alam, a 31-year-old-Rohingya of Balukhali camp, agrees with Giasuddin. “When we came here nine months ago, it was all good jungle. I myself cut 10 to 12 trees to make space for my house. I saw an elephant the day I came here. The elephant killed two persons of a family,” says Alam. “We used to go to the jungle to collect firewood. But when the rain started, we stopped going there out of fear of elephants and leeches.”

When the Rohingya, in the face of genocide in their own country, had begun to come into Bangladesh from August 25, 2017 onwards, everybody was shocked. The Rohingya influx, with nearly 120,000 people crossing the border per week at its peak, was the highest since the Rwandan genocide (according to an estimate by The Economist).

The land where the Rohingya camps were built was covered with greenery and was under the jurisdiction of Bangladesh Forest Department (FD). The FD officials tried to prevent the Rohingya from occupying the forestland. They did not anticipate then, the sheer number of people that were yet to come. “We were in the field for little over a week since August 25 to resist. But the Rohingya influx since Eid-day (September 5, 2017) was so great that we gave up. We had no time for planning. Our main purpose was to protect people,” says Md. Ali Kabir, the Divisional Forest Officer of Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division.

Environmental degradation continues

The initial days of the Rohingya influx were traumatic for the Forest Department and they watched helplessly as the Rohingya people settled in the forest land in Cox’s Bazar.

What is unique about the district of Cox’s Bazar is that officially 38 percent of its land surface is forestland and in the upazila of Ukhia alone, it is more than 50 percent. According to the office of the Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division, the state of the forest was already perilous even before the Rohingya influx in 2017-2018. Many of the 1991 cyclone victims took refuge on the forest land here in Cox’s Bazar. Development activities required cutting down parts of the forest even before. One example is land acquisition for building a cantonment and construction of the marine drive from Cox’s Bazar to Teknaf. The soil required for the marine drive was actually mined from the hills. The Forest Department did not approve of it but they were allegedly rendered powerless in the face of an ambition such as the marine drive, which after completion, is apparently very pleasing to tourists. But very few are aware of the environmental costs behind it.

The Forest Department also had to give up land for development of Cox’s Bazar town and tourism facilities that the government has been promoting. Meanwhile, the monoculture of foreign species, especially acacia and eucalyptus, has replaced garjan forests, creating a man-made disaster on pristine forest land.

Nevertheless, what happened to the forests of Cox’s Bazar since the beginning of the current influx has been nothing less than a catastrophe.

Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, the only game reserve of the country up until 2010, is just on the south-western border of Kutupalong Camp. The wildlife sanctuary started with 28,688 acres of forest land. According to the Forest Department, some 800 makeshift shelters have been erected in the sanctuary area, which is not that high a number yet, believes FD. “But the Rohingya who had started exploiting the sanctuary from the very beginning of their arrival are grave concerns for the forest and local communities,” says an official.

The destruction of the forest is not just about clearing of trees. The number of plant species and wildlife in and around the camp sites are in danger of being drastically reduced, if not completely wiped out.

According to the office of Cox’s Bazar South Forest Division, Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary alone contained 50 percent of all the mammals found in Bangladesh not too long ago, including the rare Malayan tree shrew and eight of the 10 types of primates found in the country: leopard, golden cat, fishing cat, jungle cat, hedgehog, fox, wild boar, monkey, langur, great hornbill, big grey wood peckers, and Asian elephants. Around 112 different plant species including garjan and evergreen trees and other secondary plant species grew in these hilly areas. Around 64 faunal species with high populations of 10 species of mammals, 40 species of birds, 10 species of reptiles and four species of amphibians were recorded in the sanctuary.

Sadly, the population of the elephants in the Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary, considered genetically viable, has now been separated into two groups—35 to 40 elephants are reportedly trapped in the west side of the Kutupalong camp and an equal number on the east. They cannot meet each other owing to the camps closing down the corridor they use for migration. This may prove fatal for the overall population in the future.

The male elephants may not take it easy and they may lose their temper and get violent, says Professor Monirul H Khan of Jahangirnagar University’s zoology department. He is also a wildlife photographer.

“The elephants travel a lot for feeding. The same herd of elephants uses the same corridor for generations,” says Khan.

That elephants may lose temper has already been demonstrated. “It happened seven months ago when a big elephant forayed into our house at 12:30 am. We were asleep. The elephant smashed our house. It killed my two children, four-month-old Yasmin Ara and six-year-old Mujibur Rahman. The elephant stepped on my hip and crushed it. I was given primary treatment at Kutupalong Hospital and afterwards, I took treatment at Malumghat Hospital for a month,” says Nurjahan, 45, propped against the bamboo walls of her makeshift hut in the Balukhali campsite.

Nurjahan cannot walk normally and cannot go out of her house any longer. When we went to see her on June 15, she could only stand using the bamboo pillars of her hut for support. The camps in Balukhali and Jamtoli areas are close to Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary area.

Nurjahan’s two children are among a dozen people killed by elephants.

The corridor for elephants that travel up to Teknaf Wildlife Sanctuary from the east has been severely disturbed by the freshly-built Rohingya shelters that currently host a population next to the third largest populated city in Bangladesh. Kutupalong Refugee Camp is not a city but some jokingly refer to it as the fourth largest city of the country.

A new emergency

The entire population of Ukhia and Teknaf (471,768 according to 2011 census) are largely dependent on firewood for cooking their daily meals. They were heavily dependent on nearby forest land for firewood. Now a million Rohingya have been added to this population, thus increasing the demand for firewood.

“Massive deforestation has been taking place. Forests equivalent to three to four football fields are being cleared every day,” adds Paul Quigley, energy specialist of UNHCR in Cox’s Bazar, “They cannot cook their meals if they do not collect firewood.”

The Rohingya first cut down every standing tree in the camp sites (however, there was no traditional garjan to cut; those had already gone). They cut young planted trees, most of them exotic. Then they uprooted the stumps and roots. Everyday Rohingya men are seen arriving with loads of firewood, including stumps and roots of trees.

The current Rohingya influx has significantly affected local communities and their environment. “The host communities—350,000 people living close to the camps—have been directly affected,” says Subrata Kumar Chakrabarty, livelihoods officer of UNHCR. “People of the host communities have lost crops.”

The loss of forest and presence of such a large Rohingya population in Ukhia in particular has been disturbing for the ‘host’, community. “We, the villagers used to graze our animals in the forest, fish in the creeks and small lakes, collect firewood and could roam around the area freely. Now without the forest, there is no grazing land for our cows and goats and we have no access to the area,” laments Giasuddin.

The environmental effects of the Rohingya go far beyond Ukhia as well. Bamboo supplied to the Rohingya for construction of their shelters comes in large quantities mainly from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Ora, mitinga, muli, bariwala (large)—all sorts of bamboo are being cut in excess and sent to the Rohingya camps. This has a negative effect on the environment in the CHT that has already lost much of its glory associated with its bamboo resources.

The loss of top soil in the hills that shelter the Rohingya people is obvious. This intensifies the fear of landslides in the camp sites that have some similarities with the landscapes of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). This year landslides have not been a serious issue in the camp site yet, but the risk remains as most of the land has been turned barren increasing the likelihood of landslides.

Simultaneously, huge quantities of synthetic materials such as polythene, plastic and tarpaulin are being used to create shelters for the Rohingya people. And irresponsibly disposing plastic and other non-biodegradable items will be detrimental to the future composition of the area’s soil.

Other sources of concern

Pollution in the form of light, noise, water and air are other severe causes for concern. Artificial light from the camps disrupts the nocturnal activities within the forests and so hinders wildlife reproduction ultimately affecting the species’ population. Noise from within the communities, vehicles moving in the camp site and service providers having suddenly increased further creates disturbances for wildlife in the surrounding areas.

Other serious concerns are related to WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene). Drinkable water is short in supply in Cox’s Bazar, especially in the Teknaf upazila. Therefore, access to drinking water has become even scarcer mainly in these upazilas where the refugees have settled. This will affect both the host community and the refugees, especially during the dry season.

The government is struggling to contain the water and air-borne diseases carried by Rohingya who had limited access to vaccinations and healthcare in their country. Diseases like diphtheria, respiratory tract infection, diarrhoea, dysentery, and skin diseases are very common in the camps, which may cause an outbreak beyond the camp, putting the host communities at high risk.

The latrines in the camps were built on an emergency basis when the massive Rohingya influx began in August last year. Many of the latrines are built too close to the shelters, on steep slopes, and close to canals and creeks, which are not easily accessible. Over 48,000 emergency pit latrines were installed, out of which an estimated 17 percent are now non-functional (Joint Response Plan Report 2018).

Is there a fix?

Finding a fix to environmental damages done to Ukhia and Teknaf before and after the Rohingya influx may prove extremely difficult, if not impossible, unless drastic measures are taken. For finding a long-term fix to this crisis, the Rohingya refugees should not be used as scapegoats. They are a people who have lost all their possessions back home in Myanmar and are struggling simply to survive in the camps. But in the past, in addition to plantation of exotic species, organised gangs allegedly in collusion with the Forest Department did severe harm to traditional garjan forest and used the Rohingya as scapegoats.

Currently what is needed is a rapid halt to the use of firewood for cooking purposes. The best alternative is bottled Liquid Petroleum Gas. As of early June, of this year, only 25,000 refugee families had been using it, informed the UNHCR energy expert Paul Quigley, who spoke to these writers on June 12, 2018. Borrowed from other mass refugee crises, it proves to be the cleanest and safest option. With its low emission rates LPG is the most efficient source of energy that is widely available in Bangladesh. “Companies supplying it are confident that they can bring 200,000 bottles in the camps,” says Paul.

The top soil in the hills with shelters is completely exposed, which should be covered as fast as possible. “We are planning to plant trees and encourage the Rohingya to grow vegetables,” says the UNHCR energy expert. The Forest Department also advises that the organisations and agencies (state and non-state) helping the Rohingya should consider making tree planting a regular activity in their efforts. “The Rohingya must be stopped from further expanding their territory into forest land,” says a top Forest Department official in Cox’s Bazar. “However, the FD is helplessly watching Rohingya trespassing.”

It is imperative to focus on neutral and specific research in the matter to be able to take the right policy decisions and actions to combat further environmental degradation.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing, and filming on environment for three decades. The writer acknowledges the contribution of Sabrina Miti Gain and Antarah Zaima Rahim in writing this report.