by admin | Mar 10, 2010 | Newspaper Report

The Garo Women in Bangladesh: Life of a Forest People without Forest by Philip Gain, first published in World Rainforest Movement (WM) Bulletin No. 152 March 2010.

Sicilia Snal (25), is a Garo woman of the forest village Sataria in the Modhupur sal forest. It is merely a 62 thousand acres forest patch, yet the third largest forest of Bangladesh, a country having one of the lowest per capita forest coverage on earth. Sicilia has to routinely visit the nearby forest to collect firewood. This is a traditional right that she and other villagers have always enjoyed.

Nowadays this historical native forest has lost all but its name. It has come down to less than ten per cent of its original size. This has made the life of the Garos, who still try to cling to the forest, challenging. Many have been killed, tortured, put into jail on false cases, women raped and made to migrate to cities to become industrial workers, beauticians, housemaids, etc.

With little formal education in the remote village, Sicilia supplements cash income for her family by selling labour on a daily basis. An additional burden placed on her is the collection of fuelwood from the nearby forest that has been reduced to mere shrubs.

Her life dramatically changed on 21 August 2006. Early in the morning on that day she went to collect firewood as usual. On her way back home, she and a few other Garo women put down their head loads to take a rest for a while. All of a sudden, to their great surprise, a forest guard shoots her from behind with his gun. Sicilia is hit. More than a hundred pellets enter her body; some penetrate her gall bladder and kidney. She fell unconscious. A surgery at a medical college in the nearest town [Mymensingh] removes her gall bladder.

Some pellets still remained in her kidney and could only be removed after she gave birth to her third child. With about a hundred pellets all over her back and hands, she is now restricted from any hard work. Like in other cases, she has not got justice in court. Her case is added to a few thousand other cases that are still pending in the local court.

Bihen Nokrek (35) of Joynagachha, another forest village, was shot to death by the Forest Department (FD) guards in the wee hours of 10 April 1996. A one-member judicial inquiry committee headed by a local court magistrate, produced only a final report, which, according to a FD source, said that the fire [that killed Bihen] had been justified. Bihen Nokrek leaves behind his wife and six children only to languish in poverty and insecurity.

Renu Nekola, a Garo woman of Kakraguni Village in the same area served more than a month and a half in jail for “damaging forests” in 1992. According to Nekola, she was arrested while collecting firewood from the forest on 12 December 1991. Nekola, with a small axe in hand, was caught and charged with cutting a live tree. The magistrate of a local court punished her with one month in jail. However, she had already served one month and 23 days in jail before getting the verdict under the forest act.

Sicilia Snal, Bihen Nokrek and Renu Nekola are descendants of a matrilineal Garo tribe that first settled to this forest centuries back. They had a long journey from Tibet. The majority of the Garos live in the Indian State of Meghalaya. The forest was dense and full of life at one time. The people grew everything. For centuries they used to practice slash and burn cultivation as well on the high land, locally known as Chala.

In the matrilineal Garo society women own property, do everything, can independently choose their husbands, and are seen everywhere doing all types of hard work in the fields and houses with an air of freedom, in sharp contrast with women in the Muslim majority society. While in the Muslim society the women are bound by many restrictions, the Garo women are equal to their men. They smoke tobacco and drink with their men. They do not get too angry if some have committed even adultery. Offences committed can be peacefully settled in exchange for a few pigs that are consumed by the whole village in a festive mood. This is a beautiful people with beautiful minds growing in the forest. This picture is never to be seen in the majority Bengali villages.

These children of forests, who once lived a peaceful life in the forest villages, are now exposed to the outside world due to the fast vanishing forest. The recent major factor for the dramatic loss of native forests in Modhupur and elsewhere is monoculture plantation with exotic eucalyptus and acacia trees funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank. The monoculture plantations in short rotations have severe and multiplier effects. More recently, outsiders have initiated massive-scale commercial banana and pineapple plantations among other things.

Without forests, the life of the Garo women in particular has become tough and risky. Fuelwood and forest foods that women have always collected from the forest have become scarce. They still go to the forest that is reduced to mere undergrowth and have to face “goons and guns”. The Forest Department armed guards, the military at times, groups of forest bandits, and the traders from outside —all together— cause insurmountable difficulties for the Garo women in particular. Sicilia Snal and Renu Nekola are just two of thousands of women who face bullets, rape and other types of harassment in their daily lives in the forests.

The severe deforestation, plantation and invasion by outsiders into the forest villages force the Garo women to migrate to the cities. A stunning fact about the Garo women in the capital Dhaka is that if you visit any beauty parlour [for women], you will see Garo girls working quietly and smilingly. They are also found in the physiotherapy centres. They are the ones most trusted as housemaids in the houses of the foreigners. A few thousand Garo girls and women, uprooted from their land and forest, make an eye-catching difference in the capital. They are exceptional women with very different values. Types of work that “pollute” other women from patriarchal societies cause them no “pollution”. Their psyche makes them truly equal to men. So wherever they are, they are the change makers.

The Garo women take the income that they make in the cities back to their villages. The forest has disappeared from around most of their villages, but they stand strong and teach people in other societies the lessons they need to learn. They smile against all odds they face. They do not have titles to the land they build their houses on in the forest villages, but they are the ones who hold the seeds of the forest. Given a chance, the forest can flourish again if in their hands.

By Philip Gain, Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), Bangladesh, email:sehd@citech.net

by admin | Jun 6, 2009 | Newspaper Report

by Philip Gain looks at the struggle of the labourers in the tea gardens, FORUM, A Monthly Publication of The Daily Star, June 2009.

Philip Gain looks at the struggle of the labourers in the tea gardens

Conditions on the tea gardens were grim. In 1911 the Head of Government in Assam spoke out against a labour system that, “treated its workers like medieval serfs.” Every few years new laws were drawn up in an attempt to impose minimum standards to protect the labourers on the plantations but these laws were largely ignored and unenforced, particularly as the local magistrates were planters. Companies used beatings, fines and imprisonment to keep their workers in line. Under British imperial laws trade unions were forbidden on the estates. Organisers who attempted to contact tea pickers were seen as trouble makers and accused of trespass. –British writer Dan Jones, 1986. “The tea gardens are managed like an extreme hierarchy: the managers live like gods, distant, unapproachable, and incomprehensible. Some even begin to believe that they are gods, that they can do exactly what they like.” — Francis Rolt, British journalist, 1991.

“Managers have anything up to a dozen labourers as their personal, domestic servants. They are made to tie the managers shoe laces to remind them that they are under managerial control and that they are bound to do whatever they are asked.” –British writer Dan Jones, 1986.

Tea, the second most popular beverage in the world (the first is water), is believed to have first been popularised in China. For thousands of years the Chinese farmers had the monopoly of cultivating tea. Its cultivation in the tropical and subtropical areas is a recent phenomenon.

Tea plantation in India’s Assam dates back to 1839. The first experimental tea garden in our parts was established in Chittagong in 1840 and the first commercial-scale tea garden in Bangladesh was established in 1854. Since then the tea industry has been through quite a few historical upheavals — notable among them are the Partition of India in 1947 and the Independence War in 1971. Through these historical changes, the ownership of tea gardens established by the British companies on the abundantly available forest or government land has changed hands.

Right now Bangladesh has 163 tea gardens (including seven in Panchagarh where tea cultivation started only recently) with 36 of them considered “sick.” One unique feature of the tea industry is that the entire land mass (115,000 ha excluding Panchagarh) granted for production of tea is government land. It is also for the colonial legacy that our tea gardens are huge in size and the management administer the gardens with the air of British Shahib and Zamindars. The use of grant areas for tea with 45% actually used for production of tea is another key concern. Land granted for tea cultivation but used for other commercial purposes is deemed unjust and an incentive for social injustice perpetrated on the tea plantation workers.

them considered “sick.” One unique feature of the tea industry is that the entire land mass (115,000 ha excluding Panchagarh) granted for production of tea is government land. It is also for the colonial legacy that our tea gardens are huge in size and the management administer the gardens with the air of British Shahib and Zamindars. The use of grant areas for tea with 45% actually used for production of tea is another key concern. Land granted for tea cultivation but used for other commercial purposes is deemed unjust and an incentive for social injustice perpetrated on the tea plantation workers.

Photo: PHILIP GAIN

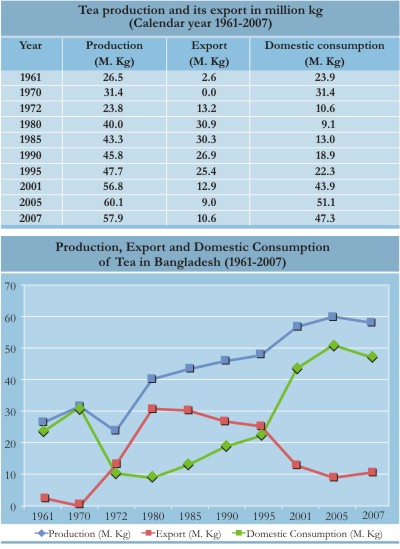

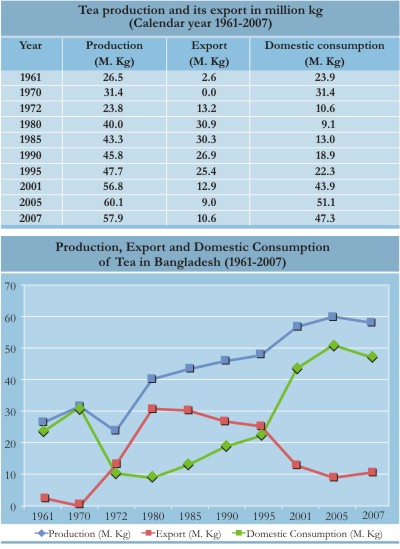

The most striking fact about tea production in Bangladesh is that after the partition of India most of the tea produced here used to be consumed by West Pakistan. After Independence, Pakistan remains to be the largest importer of Bangladeshi tea. However, now it is we who consume most of the tea that we produce. In 2007 Bangladesh produced 57.9 million kgs of tea of which only 10.6 million kgs were exported [82% of which was taken by Pakistan]. There is an apprehension that if the production of tea does not increase significantly and if domestic consumption continues to grow fast, Bangladesh will soon become an importer of tea. The bottom line is tea is no more an important export commodity and Bangladesh plays no significant role in the global tea trade although it ranked 10th among the tea-producing countries in 2007.

In the discussion on tea, its production, consumption and trade those who remain least attended are the tea plantation workers. The tea industry is very different from other industries. The production process of tea involves agriculture and industry. What is unique about labour distribution in these two areas is that the maximum of the labour force is engaged in agriculture — the tea gardens or the field. The labour force that keeps the tea industry alive is not local. The British companies brought them from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens in the Sylhet region. The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens. According to one account, in the early years, a third of the tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to the tough work and living condition. Upon arrival to the tea gardens these laborers got a new identity, coolie and were turned into property of the tea companies. These coolies belonging to many ethnic identities cleared jungles, planted and tended tea seedlings and saplings, planted shade trees, and built luxurious bungalows for tea planters. But they had their destiny tied to their huts in the “labour lines” that they built themselves.

When they came first, they got into four-year contracts with the companies. That was the beginning of their servitude. More than a century and half or four generations have passed since the tea plantation workers settled in the labour lines. Their lives and livelihoods remain tied to the labour lines ever since. They are people without choice and entitlement to property. In addition to the wages, which is miserably low, they get some fringe benefits. The houses in the labour lines are given by the employer that comes first on the list of fringe benefits. One worker gets one house that is supposed to be maintained by the employer. However, generally the workers themselves do the repair and maintenance. Living conditions in houses in the labour lines are generally unsatisfactory and outrageous in many instances. Typically a single room [in the line house] is crowded with people of different ages of a family. Cattle and human beings are often seen living together in the same house or room. Some families try to construct an extra house or room for which they have to take permission from the management.

The wages — daily or monthly — is the single most concern. The maximum daily cash pay for the daily rated worker in 2008 was Taka 32.50 (less than half a US$). This is a miserable pay having a severe effect on the daily lives of the tea workers. Although the workers get rations at a concession, a family can hardly have decent food items on their plate. They indeed have very poor quality and protein-deficient meals. Their physical appearance tells of their malnourishment. Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU) that represents the workers and Bangladesh Tea Association (BTA) that represents the employers sign a memorandum of agreement every two years to fix the wages. The last memorandum of agreement went into effect on 1 September 2005. The two-year period of effectiveness of the agreement ended on 31 August 2007 [during the state of emergency in the country]. It was due to the state of emergency and squabbles between rival groups in Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union that no agreement between the two parties was signed in due time. However, in the absence of any agreement, the owners increased wages by Taka 2.5 as an interim arrangement. What is important to note here is that BCSU in its charter of demands placed to the owners have demanded increase of wages by up to 100%, but the owners increased it by Taka 2 every two years, which the BCSU accepted in the end. The newly elected leadership (in 2008) of the BCSU, in its charter of demands of 2009, demanded that the cash pay of the daily rated workers be increased to Tk.90.00 from Tk.32.50. It is yet to be seen how the employers respond to the demands of BCSU.

Fringe benefits other than houses include some allowances, attendance incentive, rations, access to khet land for production of crop (those accessing such land have their rations slashed), medical care, provident fund, pension, etc. BTA calculates the cumulative total daily wage of a worker at Tk.73. The newly elected leaders in BCSU have a different calculation, which is lower than that of BTA.

For a long time, The Tea Plantations Labour Ordinance, 1962 and The Tea Plantation Labour Rules, 1977 defined the welfare measures of the tea plantation workers among other things. In 2006 these laws along with other labour related laws (25 in total) were annulled and a new labour law, Bangladesh Labour Act 2006, was introduced. The tea plantation workers were brought under this Act. The new Act has fixed the minimum wages of industrial workers at Tk. 1,500 (US$22). The tea plantation workers, who got lower wages in cash than this minimum wages, raised their voices for an increased cash pay. They were turned down. In a letter dated 20 July 2008 the Deputy Director of Labour, Tea-industry Labour Welfare Department in Srimangal, Maulvibazar announced, “the minimum wages announced in the gazette was not for the workers in the tea gardens.” The letter also mentioned that “the government has already formed a separate wage board to determine the wages for the tea workers and the issue of minimum wages is under consideration.” It is yet to be seen how the wage board makes progress in its work.

For a long time, The Tea Plantations Labour Ordinance, 1962 and The Tea Plantation Labour Rules, 1977 defined the welfare measures of the tea plantation workers among other things. In 2006 these laws along with other labour related laws (25 in total) were annulled and a new labour law, Bangladesh Labour Act 2006, was introduced. The tea plantation workers were brought under this Act. The new Act has fixed the minimum wages of industrial workers at Tk. 1,500 (US$22). The tea plantation workers, who got lower wages in cash than this minimum wages, raised their voices for an increased cash pay. They were turned down. In a letter dated 20 July 2008 the Deputy Director of Labour, Tea-industry Labour Welfare Department in Srimangal, Maulvibazar announced, “the minimum wages announced in the gazette was not for the workers in the tea gardens.” The letter also mentioned that “the government has already formed a separate wage board to determine the wages for the tea workers and the issue of minimum wages is under consideration.” It is yet to be seen how the wage board makes progress in its work.

If compared with wages of the Indian tea workers, the wages of Bangladeshi tea plantation workers is much lower. In Darjeeling, Terai and Doars of West Bengal in India the daily wages of a tea plantation worker was Rs.53.90 in 2008. The wages, increased in three steps, will reportedly become Rs.67 in 2011. Strong labor movements have been instrumental in such wage increase. In West Bengal about 400,000 workers will get this increased wages. Compared to the Bangladeshi tea plantation workers, the Indian workers also get a better deal in accessing fringe benefits such as rations, medical care, housing, education, provident fund benefits, bonus, and gratuity. What puzzles one is that the auction of prices of tea in Bangladesh is high compared to the international auction prices while its production cost is comparatively lower than other tea producing countries (India, Sri Lanka and Kenya for example). Of course the productivity of tea per unit in Bangladesh is lower compared to those countries. Many believe that there is no justification for low wages of the tea plantation workers in Bangladesh. They deserve much higher wages.

The work condition of the tea workers who spend most of their working time under the scorching sun or getting soaked in rains is a concern. A woman tealeaf picker spends almost all her working hours for 30 to 35 years standing before she retires. The working hours for the tealeaf pickers, mostly women, are usually from 8 AM to 5 PM [7-8 hours excluding break for lunch] from Monday to Saturday. Sunday is the weekly holiday. To earn some extra cash, the extra work brings additional grief.

PHOTO-PHILIP GAIN: Education, an important ladder for transformation of a community or society for betterment is at the root of the social exclusion of the tea workers. There are schools in the tea gardens. According to the Bangladesh Tea Board (2004), in 156 tea gardens (excluding those in Panchagarh) there were 188 primary schools with 366 teachers and 25,966 students. Given that the employers provide education, the government schools in the tea gardens are just a few. In the recent times, the NGOs run significant number of primary schools. The quality of education provided in these schools remains to be a concern. An overwhelming majority of the children of the tea plantation workers drop out from school before they can use education to step into other professions and thus they have to enter the tea gardens as laborers.

PHOTO-PHILIP GAIN: Education, an important ladder for transformation of a community or society for betterment is at the root of the social exclusion of the tea workers. There are schools in the tea gardens. According to the Bangladesh Tea Board (2004), in 156 tea gardens (excluding those in Panchagarh) there were 188 primary schools with 366 teachers and 25,966 students. Given that the employers provide education, the government schools in the tea gardens are just a few. In the recent times, the NGOs run significant number of primary schools. The quality of education provided in these schools remains to be a concern. An overwhelming majority of the children of the tea plantation workers drop out from school before they can use education to step into other professions and thus they have to enter the tea gardens as laborers.

The tea communities are one of the most vulnerable people of Bangladesh. They deserve special attention of the State, not just equal treatment. But unfortunately they continue to remain socially excluded, low-paid, overwhel-mingly illiterate, deprived and disconnected. They have also lost their original languages in most part, culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. In the labour lines of a tea estate, they seem to be living in islands — isolated from the majority Bangali community who sometimes treat them as untouchables. Without fertilisation of minds, they have lost dignity in their lives. These are perfect conditions for the profiteers from the tea industry to continue exploitation of the tea workers. Deprived, exploited and alienated, the majority of the tea workers live an inhuman life.

The key questions to ponder: How longer will the tea communities stay confined to the labour lines? Will they continue to live as people without choice and entitlement to a land they have tilled for four generations? The employers probably want the status quo maintained for a steady supply of cheap labourers. But the tea communities, little more conscious now than before, want justice done to them. They want strategic services from the State and NGOs in the areas of education, nutrition and health, food security, water and sanitation, etc. They also want to see their languages, culture, and social identity protected.

Photo: PHILIP GAIN

Photo: PHILIP GAIN

Fearful of their future in an unknown country outside the tea gardens, the tea communities keep their voices down and stay content with meager amenities of life. As citizens of Bangladesh they are free to live anywhere in the country. But the reality is that many of the members of the tea communities have never stepped out of the tea gardens. An invisible chain keeps them tied to the tea gardens. Social and economic exclusion, dispossession and the treatment they get from their management and Bangali neighbours have rendered them to become captive labourers.

The government is showing the country a dream of a digital Bangladesh and changes in the lives of poor, marginal and Adivasi people. The tea plantation workers are not just poor, they are a particularly deprived marginal community in captive situation. They have limited scope to integrate with the people of the majority community and they face great difficulties in exploring livelihood options outside the tea gardens. The tea plantation workers want the State to address to address their case with care and translate its commitment to them providing political and human protection.

Philip Gain is the Director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

by admin | Jan 1, 2008 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain makes a painful visit to find the World Heritage Site devastated, though hope still flickers. FORUM, a monthly publication of The Daily Star January 2008 (Volume 3, Issue 1)

Philip Gain makes a painful visit to find the World Heritage Site devastated, though hope still flickers

A week after the cyclone, as we see the effet of the calamitous Sidr in some parts of the Sundarbans, we are pained. The greenery of the most majestic mangrove patch on earth has faded out. It looks brutally molested. The Sundarbans always takes hits from the violent Bay, but nobody has a memory of such damage that a cyclone and tidal surge has caused.

A week after the cyclone, as we see the effet of the calamitous Sidr in some parts of the Sundarbans, we are pained. The greenery of the most majestic mangrove patch on earth has faded out. It looks brutally molested. The Sundarbans always takes hits from the violent Bay, but nobody has a memory of such damage that a cyclone and tidal surge has caused.

A month and half ago before the cyclone, I was in a group of seven photographers that spent ten days in the eastern part of the Sundarbans. We floated through the Sundarbans for all those days and nights. Our everyday trip in a small boat through the intricate web of nature, sometimes threatening to human life, was a real thrill.

With lower salinity level compared to the western part, this part with high vegetation is full of wildlife and other life forms. Roaring tigers, pugmarks in several places, flocks of deer and monkeys, coloured birds and snakes in hundreds, wild pigs, meadows, and columns of lush green vegetation — all remain sharp in my memory.

My memory was shaken when I went back to the cyclone-devastated eastern part of the Sundarbans on November 23. We had already known from newspaper reports quoting the sources in the Forest Department that “one-fourth” of the 6,017 sq. km. Sundarbans has been badly hit by winds of 250 km per hour and a 5-metre tidal surge.

Our first stop to take a close look over the fate of a forest office is Harintana in Chandpai Range. We are appalled to see the impact of Sidr. The forest office, including the jetty, has been completely demolished. Bits and pieces of wood are scattered all over the office premises. A trawler has been thrown up on the ground from the canal by the tidal surge. The trees have been twisted, broken, and the green leaves all gone. We find a few Forest Department (FD) employees of the station on their patrol boat.

“The winds, rain, and waves lasted for hours. We boarded our patrol boat and took refuge in a canal. We survived 10-12 feet high waves,” says FD boatman Md. Idris Alam. The FD staff of this office had been living on the patrol boat since the cyclone day. They don’t go on the ground for fear of the unknown, including tiger attack.

As we move further down, we are deeply shocked at the devastation caused to the mangroves, a natural shield for human habitation against winds and tidal surges. Had the forest not been there, the cyclone could have been deadly for the nearby towns — Khulna, Mongla, and Bagerhat. The forests took the brunt of the winds and tidal surges, and saved these towns from severe devastation. Experts believe that the forest will gradually recover. But if the cyclone had hit these towns, the economic fallout would have been much more calamitous.

We take a look at the forest office at Tiar Char only to find the office destroyed and deserted. What remains of the office are the cracked walls. The roofs, windows, and doors have blown away. The trees are broken and twisted. Everything looks burned down. We don’t have the courage to land.

We head for Kokilmoni with the same devastation on the both sides of the river. As we come near to the forest office at Kokilmoni, we see just one deer and one wild pig. We spent a night and a morning at Kokilmoni a month and half ago during our 10 day trip to the Sundarbans. Kokilmoni office premises is known for deer. We saw scores of deer in flocks then. In the morning as we took to a narrow canal in our small boat, we had a terrifying experience. We came across a roaring tiger. We did not see the tiger although it was some 50 feet away from us in the bush. The tiger was shaking the jungle every time it roared. It was mating season for the tigers and the roaring one was probably inviting a partner. As we had been hoping that the tiger would cross the canal, we saw a vine snake on mangrove shrub basking in the sunny morning. It was terrific to be so deep into nature

The cyclone has undoubtedly wiped out large quantities of deer, snakes, insects, wild pigs, and many other life forms.

The damage to Kokilmoni forest office has been massive. There is no sign of the jetty. The roofs, windows, and doors of the office building have been blown away. Finding the office premises uninhabitable, the FD employees have deserted it. We find some ten fishermen’s boat. Some of them were at Kokilmoni during the nightmare. Three boats and six nets have been washed away from here. However, no one died. The fishermen took refuge in the canal and were lucky enough to have survived the winds and tidal surge by holding on to the trees.

Our launch anchors at Kokilmoni to wait for the ebbing tide. Our next destination is Dublar Char, which actually encompasses 11 pancake shaped low-lying islands. Next morning as we approach Dublar Char we are dismayed to see broken, twisted, and uprooted trees. We see no tree standing with green leaves on the banks of the channels. We see a few sea gulls and eagles, but no other birds. The cyclone has rendered the forest barren and silent. We see the forest office at Office Killa in Dublar Char from a distance. The tin-shed house on concrete structure is still standing. As we go closer, we see that all the doors and windows and the tin-shed roof of the office building have been thoroughly torn apart. The walls are fractured. A wooden house on its right has been washed away.

There is a cyclone shelter at Office Killa. Md. Alauddin, acting in-charge of the Dublar Char forest office, still in trepidation, narrates: “Some 700 people took refuge in the L-shaped cyclone shelter. The winds began to flow at about 5:00 pm. The strongest ones hit at about 9:30 pm. The big wave that lasted for hardly 15 minutes almost flooded the first floor of the shelter. Had the water stayed for another ten minutes, the cyclone shelter would have collapsed. It was shaking as water hit and receded.” We find the base pillars of the cyclone shelter cracked.

A mosque on the side of the cyclone shelter has been completely destroyed and washed away.

Md. Osman, a fish worker took refuge in the mosque. “As the water began to flow into the mosque, I managed to climb on the nearby cyclone shelter. My companion, who also tried to reach the cyclone shelter, was washed away by the strong wave. We later found him dead,” says Osman.

Photo: Philip Gain

Photo: Philip Gain

Md. Abul Quashem, a caretaker of the Cyclone Preparedness Program of Bangladesh Red Crescent Society in Dublar Char, tells his experience of the cyclone. “We have our wireless facility in Office Killa cyclone shelter. We blew siren and invited people to come to safety. The fishermen did not want to come leaving behind their boats, nets, and dried fish. Many took refuge in the canals with their boat. Most of them have perished,” says Abul Quashem.

The fish workers who did not take refuge at the cyclone shelter became the worst victims. “In Dublar Char, we have known that 201 people have died,” reports Quashem.

According to Quashem, there were 19 bohoddars (fish traders) in Majher Killa and Office Killa alone. Each bohoddar brought between 80 and 150 individuals for fishing and its trade. During the cyclone, there lived 2,500 fishermen in Majher Killa and Narikelbari alone, and 20,000 in the entire Dublar Char area.

“The bohoddars are not giving actual numbers of people missing. Majority among the missing are dolabhanga (individuals who sort out fish and get a share),” claims Quashem. Dolaghangas are said to be collected from rail stations, slums, and streets of the cities. Dolabhangas did not come to the cyclone shelters, which also did not have enough space for them, even though they wished to come. This group of labourers in the fish drying centres died in great numbers.

As we reach Shelar Char, we find a cyclone shelter and a few boats and trawler anchored. The fishers are busy repairing their nets, boats, and temporary makeshift houses. More than 2,000 fishermen lived here for fishing in the open bay.

Many of the fishermen we see here survived the cyclone. Some took shelter in the cyclone shelter. “A big number risked their lives in the canals. I survived by holding a tree,” said Md. Isaboli Hawladar from Pirojpur who works under bohoddar Md. Aiyub Ali. The fishers got signal of the cyclone, but many did not pay much attention to it and others did not have time to make it to the cyclone shelter.

Khalil, Surat Hawlader, and Monir from Pirojpur took shelter on a keora tree. Most of the boats anchored in the canal of Shelar Char were lost. Many fishermen perished with their trawlers.

Katka stands lifeless

Our launch navigates through the open Bay from Shelar Char. Hard to believe that this serene bay becomes so cruel. Now we see the Sundarbans from quite a distance. However, the line of trees merging with the waters seems to have been burned down.

Photo: Philip Gain

As we go near to Katka, we are shocked to see how the forest has become lifeless. Katka is one of the best-known wildlife sanctuaries and an attractive tourist spot. The forest office here has always been lively with a column of forest office buildings, guesthouses and visitors. It’s a spot where one would see deer in hundreds, wild pigs, birds, monkeys, and, if lucky enough, a tiger.

It is hard to recognise the mouth of Boyer Khal (canal) on the east of Katka FD office. We took a boat ride through this canal on October 3 this year. For me it was an experience that will never disappear from my memory. Everything was deep green. Keora and many other trees were full of green leaves and fruits — food for birds, monkeys, deer, and millions of other creatures. The song of mangrove whistler and other birds, flocks of monkeys and deer, white-bellied sea eagle and open-billed stork (shamukkhol) flying above filled our minds and hearts with complete joy. As we went deep into the forest, we always kept our binoculars and eyeballs pointed at different directions in search of a tiger. We always stayed alert about the snakes. We, indeed, spotted some venomous snakes from our constant vigilance. All these wildlife seem to have vanished.

We land at Katka forest office barefoot, because the jetty has been destroyed. What we see goes beyond description. The wooden houses have no trace. The concrete houses have been piled into debris. The column of beautification trees — jhaw, coconut, and others in front of the forest office has been broken, twisted, and blown from here to there. The forest around the office, a haven for the deer, wild pigs, and the birds, has become lifeless with twisted and broken trees.

We land at Katka forest office barefoot, because the jetty has been destroyed. What we see goes beyond description. The wooden houses have no trace. The concrete houses have been piled into debris. The column of beautification trees — jhaw, coconut, and others in front of the forest office has been broken, twisted, and blown from here to there. The forest around the office, a haven for the deer, wild pigs, and the birds, has become lifeless with twisted and broken trees.

A month and half ago, when we spent a few nights at Katka, every morning we woke up to see hundreds of deer feeding on keora leaves, madantak and many other birds feeding on muddy slope of the river banks during the ebbing tide. Some wild pigs could be sighted in the morning and the evening. We walked a mile into the forest in the hope of tracing a tiger. Although we could not trace one, we found fresh pugmarks. It was terrific.

What the cyclone has done to this heaven of wildlife looks like the aftermath of a total war. The trees have lost their leaves and branches. A great number of trees have fallen on the ground. There were two palm trees named king and queen. The queen was twisted and uproot and flown some 100 metres away. The base of the king and queen looked burned.

There were five FD employees at Katka during the night of November 15. All of them miraculously survived the winds and waves. But many unlucky fishermen in rivers and canals were missing.

Ray of hope

We head from Katka to Kachikhali, another haven for wildlife. It is afternoon. Everything glows in golden sunshine. It is time of the day to see some unique creatures that might suddenly emerge from the forest.

We are not disappointed although we cut through the devastated Sundarbans. As we take to a narrow canal, we sight a masked finfoot. A bird watcher is always excited to sight this rare and endangered solitary duck.

We are not disappointed although we cut through the devastated Sundarbans. As we take to a narrow canal, we sight a masked finfoot. A bird watcher is always excited to sight this rare and endangered solitary duck.

From the narrow canal, we enter a big river. Now we head for Kachikhali. We see some greenery. It is soothing. We see a large crocodile, basking in the evening sunshine. It is ebbing tide, time for crocodiles to relax on the muddy slope of the riverbank. A few birds are roaming around it. The fat crocodile seems to have no appetite.

We move forward. Now we see more life — monkeys and deer feeding on the molested, vegetation. We feel assured that the animals have a chance. We reach Kachikhali shortly. Dimer Char or Egg Island, about one km south into the sea from Kachikhali shore, is an attraction to the birders. Dimer Char still been hit hard by the winds and waves. Three fishermen died in this island. They perished with their boat. Eleven fishermen survived.

During our last visit before the cyclone, we took a boat-ride along a canal that cuts through the island. Full of green vegetation, mostly keora and understory, the forest looked virgin and a heaven of birds.

As we venture to see what has happened to the Kachikhali forest office, we feel sorry. When we came here last September, we had a comfortable landing by a well-built jetty. That has been completely destroyed. We land barefoot. All but one building have collapsed. Trees have fallen down. Not only the roofs of the houses have blown away, the concrete walls have fallen apart as well.

Heaven for deer and hunting ground for tiger, the lush green meadow with a carpet of sun grass and kash (thatch grass) has become miserable. We can imagine what may have happened to the wildlife in this area that merges with the bay. Darkness begins to fall and we board our launch. The full moon emerges over Dimer Char. The sea is quiet. No noise of wave. We see just one small fishing trawler on the shore. There is none in the sea. No dancing light. Our launch moves back as the night falls.

Heaven for deer and hunting ground for tiger, the lush green meadow with a carpet of sun grass and kash (thatch grass) has become miserable. We can imagine what may have happened to the wildlife in this area that merges with the bay. Darkness begins to fall and we board our launch. The full moon emerges over Dimer Char. The sea is quiet. No noise of wave. We see just one small fishing trawler on the shore. There is none in the sea. No dancing light. Our launch moves back as the night falls.

Recovery

Estimating the extent of damage to the Sundarbans is a difficult task. That one-fourth of the Sundarbans has been severely damaged as the FD officials initially guesstimated and that in monetary terms the damage is worth Tk 1,000 crore, has been highly disputed by knowledgeable sources.

There is no denial of the fact that the web of nature has been seriously disrupted in the areas hit. “There are some 280 species of birds in this unique mangroves” says Ronald Halder, an ornithologist and filmmaker who has been visiting the Sundarbans since 1992.

Sundarbans is also an extremely valuable sanctuary for snakes. “The bird and snake population must have been heavily harmed in the cyclone hit areas,” says Halder. “Insect population is huge in the Sundarbans. Now the songs of the insects are heard much less.”

During stay in the Sundarbans in September and October, insects in thousands swooped around the light of our launch. After the cyclone, no insect bothered us. Although there is no known work of entomologists in the Sundarbans, it is not difficult to understand the immense damage caused to the insect population.

“The way the trees have broken down and the green leaves destroyed, the wildlife and insects, dependent on trees, have died in great numbers. All sources of fresh water have been damaged in the cyclone-hit areas. This will affect the wildlife and fish population,” says wildlife photographer Sirajul Hossain.

A serious concern also arises from the destruction of the FD offices. A few offices we have visited have been thoroughly destroyed. This shows the flimsiness of the infrastructure in the Sundarans areas.

However, the guesstimate on damages that the FD initially aired was pretty much speculative and not well thought out. While speculations cannot always be rejected, “we must keep in mind that we do not have enough knowledge about the intricacies of the Sundarbans,” cautions Halder.

Photo: Munir uz Zaman/ DRIKNEWS

The measures that the authorities and even some experts had initially suggested made environmentalists very concerned. For example, the chief conservator of forests was reported suggesting cleaning the debris (fallen trees and leaves) from the forest floor and to go for enrichment planting in the affected areas. According to newspaper reports, one expert had even suggested removing sand that has covered the breathing shoots of mangrove trees. Many raised their concern at such suggestions.

Thanks to the one-year government ban on harvest of trees in the Sundarbans — fallen or standing — reportedly taken in an inter-ministerial meeting on December 5. In his observation made in a newspaper article, Hasan Mansur, who has frequented the Sundarbans for the last three decades, cautions that there lacks objective reporting on the damage to the Sundarbans. He thinks that five to ten percent of the mangroves have been damaged. He believes the Sundarbans will recover automatically. There is no need for human interference.

There are many others who concur with Mansur and suggest that there is no need for removing the fallen trees, leaves, and the sand that may have covered the breathing shoots of the trees. Let the leaves and fallen trees rot and fertilise the forest floor. The enormous amount of seeds that will still be spreading by the next season will automatically regenerate the forest. Green leaves will also spring up from what seem to be dead stands. We must remember that we are dealing with nature. We know little of nature and must not try to control it.

What we need at this troubled time is proper assessment building up to a national strategy to nurture the unique forest. Given that Sundarbans is a world heritage site announced by Unesco, the world body needs to define the global responsibility, and perhaps, lend a helping hand.

that Sundarbans is a world heritage site announced by Unesco, the world body needs to define the global responsibility, and perhaps, lend a helping hand.

One important endnote: Now that we better understand the force of nature, the FD needs the kind of infrastructure that can withstand strong winds and waves and give protection to those who are allowed into the forests. A large number of fishermen, honey collectors, and harvesters of nypa palm are dependent on the Sundarbans. A special rehabilitation program is required for these people so that they do not rush towards the forest in search of their meagre necessities.

Philip Gain is an environmental activist.

by admin | Aug 31, 2007 | Newspaper Report

After a few months, the Forest Department has resumed its war against banana in Modhpur) by Philip Gain, The Daily Star

Part of the Modhupur National Park. This is the forest many would like to see throughout Modhupur and Banana garden on the forestland after felling. Photo: Philip Gain

The war against “illegal” banana plantation in the Modhupur sal forest has been resumed from August 1, 2007. Throughout August, the Forest Department (FD), with support of the security personnel, has engaged hundreds of non-local labourers everyday in chopping down the banana gardens and planting acacia.

The Forest Department (FD) carried out the first round of its war against banana on 13, 14, 15 and 22 February, and 7 March. After 7 March, the government gave time to the banana cultivators and advised them to voluntarily stop banana plantation on the forestland after the harvest of their standing crops.

The Forest Department (FD) carried out the first round of its war against banana on 13, 14, 15 and 22 February, and 7 March. After 7 March, the government gave time to the banana cultivators and advised them to voluntarily stop banana plantation on the forestland after the harvest of their standing crops.

In a meeting on 9 March, the forest and environment adviser Dr. C.S. Karim, formed a 12-member committee (two chairmen of two union councils in forest area were later co-opted to the committee) including the Garos and sought suggestions from the committee as regards eco-park, protection of sal forest, land use practices, etc.

On the day of the first meeting of the committee, on 18 March, the alleged killing of Chalesh Ritchil took place. Four meetings of the committee took place ever since. However, none of the members from among the Garos and NGOs got minutes or report of any meeting.

A high official in the Forest Department (FD) said on 17 August, “Illegal banana gardens are being cut again and plantation is being carried out on land where illegal banana gardens were cut months ago. Such land amounts to 3,600 acres. Our target of chopping banana plantation this year will be fulfilled by the end of August.”

“In our current raid against banana plantation the main targets are the Bengalis who have engaged the Garos in illegal cultivation on the forestland. We will not spare any marauder on the forestland,” warned the FD official. “We want the Adivasis to participate in forestry programmes and stay protected. A Garo household participating in the forestry will get one ha of land and share benefits from plantation. We are yet to work out the details of the participation mechanism. We will consider the suggestions from the committee and experts in this regard.”

In the war against banana, the Garos find themselves in an inept condition. In the recent years, they have been indeed got heavily engaged in banana plantation that brings them quick and handsome cash. However, the top players behind the banana cultivation are the Bengali traders who brought the idea of banana cultivation on a massive scale. They also provided cash. The Garos in most of the forest villages in Modhupur even replaced their age-old gardens of pineapple, jackfruits, lemon, etc. with banana. Now they find that hope for big and quick cash banana further complicates their land questions.

With typical vegetation disappearing with the invasion of banana, the Garos are in real difficult situation in establishing their traditional rights over the high land. They normally have title deeds for the low land (baid) but in most cases, they do not have title deeds for the highland they have been occupying from time immemorial. These highlands with native vegetation were gradually declared as protected or reserved at different times after the abolition of the Zamindari system.

The Garo representatives on the committee to resolve the problem in the Modhupur sal forest say they were surprised when the raid against banana resumed on 1 August. As the days passed by the intensity of raid increased and the number of hired labourers raised.

To give an idea how the daily raid against banana takes place let us see the picture of one day. On 17 August, approximately 500 labourers, with dao (homemade chopper) and spade in hands swooped on banana gardens in Atashbari-Nayanpur area. The security personnel were present on the spot. Present on the spot were also officials of the Forest Department and administration. Few hundred Garos, most of them women, assembled and helplessly appealed to the government officials to spare the banana gardens. Their appeal was ignored and the banana plants in the area were felled.

On the same day, a similar group of hired laborers was reportedly engaged in another part of the forest to clear banana gardens. The top cats behind the banana plantation, the Bengali traders who make heavy investment in banana, remained largely unseen.

The government officials were telling the Garos that they were recovering forestland and planting trees with the consent of their leaders on the committee. However, one Garo leader on the committee refuted the claim. “The FD has not followed our decisions about planting trees in place of banana gardens,” said the leader. He complained that he has not received any reports of any of the meetings although he has asked for it repeatedly. “We agreed to plant trees ourselves; not the way it is being done now”. He also complained that no village demarcation or survey was conducted.

A high official in the FD says it is because of dearth of saplings of local species that acacia is being planted. He claims some local species have also been planted. “From next year we will plant more local species,” says the FD official.

Bringing back the forest: A tough task

Ideally, the forest of native species, especially sal, must be established after the termination of banana plants. Why? Because the exotic species — acacia and eucalyptus (planting of this alien was stopped after the first rotation) — in particular planted under “social forestry” in Modhupur have proven to be politically and ecologically mistaken. The “social forestry” itself has been blamed to be a sugarcoat for plantation.

The Garos who are seemingly innocent victims of commercial banana plantation, now find that after chopping down of banana plants acacia is being planted. The environmentalists are also very unhappy. Although some FD officials would call acacia a “soldier tree” meaning it can survive tough climate condition, this alien is perhaps good for fuelwood but cannot be a replacement for the native sal or other local species. The ADB and World Bank that funded massive-scale plantation of this alien species have withdrawn from the forestry sector altogether leaving the Forest Department and other stakeholders on a hotspot, very difficult to manage.

Therefore, while the government officials keep telling the Garos that they are out there to protect them and bring back the native vegetation, the first people of the forest who have the knowledge of traditional forest management see no direction and become even more worried.

The participation of the Garos in afforestation proposed by the FD is also not welcome by the Garos. They have the bitter experience of woodlot and agroforestry that have rapidly eaten up the native forests. Almost the same model the FD talks about brings no better option for them.

Invasion by banana

Many see the massive-scale banana plantation on the forestland as a multiplier effect of manmade “forests” among other things. The idea of this so-called manmade forest sugarcoated as “social forestry” came along the loans from the concessional window of the Asian Development Bank. In Modhupur monoculture plantation of primarily exotic acacia and eucalypts took place under two ADB funded projects — Thana Afforestation and Nursery Development Project (TANDP) and Forestry Sector Project (FSP). TANDP with two major components — woodlot and agroforestry — started in 1989 and ended in 1995. When monoculture started with the ADB loan, the local people were appalled to see that the native sal coppices were indiscriminately cut to prepare grounds for the manmade forests.

Ten years later people found most of the plantation stolen or officially harvested. The land became vacant, perfect ground for invasion by banana and papaya plantation. Pineapple was already there. Outsiders invaded the forestland for large-scale banana and papaya plantation. They lured the Garos even to convert their home gardens into banana gardens. This process started largely due to ADB’s investment strategies in the forestry sector, it is generally believed.

After the first rotation of plantation, the government awaited another loan from ADB for the Fores

try Sector Project (FSP). The project that was supposed to start in 1997 was much delayed. In the meantime, ADB made Bangladesh Government to amend the Forest Act of 1927 in favor “social forestry” that is essentially plantation. The delay caused the forestland to remain vacant for a longer period. The banana, papaya and pineapple cultivators took control of the forestland and spoiled it thoroughly in a short period. The allegation that the corrupt FD officials turned out to be accomplices for extra cash is not unfounded.

For the last few years, the Modhpur Salbon (sal forest) has gained an infamous image as Modhupur Kalabon (banana forest). According to a top FD source, the sal patches in the Modhupur survive only on 6,000 acres today (2007). According to the DFO of Tangail [in 2004] who is now hiding with corruption charges, out of 46,000 acres in Tangail part of the Modhupur sal forests 25,000 acres had gone into illegal possession and the FD controlled only 9,000 acres by 2004.

How come such massive-scale grabbing of the forestland occurred? Why did the FD [that now takes advantage of the state of emergency in recovering the forestland] stay passive? These questions need to be seriously addressed in understanding what have gone wrong in Modhupur.

The FD has apparently targeted 3,600 acres of forestland for recovery and plantation this year. What about the bigger chunks of the forestland illegally grabbed? There are many evidences how the forestland given out for plantation has been abused by the banana and papaya cultivators. There are indeed many papaya gardens illegally established on the forestland. In the war against banana, papaya plantations also illegally established on the forestland, remain unattended for now.

However, a top FD official says that they will deal with the illegal papaya plantation at a later stage.

What really need to be done?

A look over the protected parts of the Modhupur National Park from the two towers recently built in Dokholoa and Lohoria gives us a ray of hope. The monsoon greenery of the native vegetation is absolute. This is what we want gradually expanded in other parts within the forest boundaries. For that, here are some suggestions to ponder.

Thorough inventories:

Inventories as regards exactly how much of the Modhupur sal forest is left today and how much of the forestland has been illegally occupied can provide handles for right direction in saving native patches and expanding them. It is not just the banana, an inventory of papaya and pineapple gardens need to be done. A complete list of the marauders on the forestland should be made public, Then the crusade against them will become transparent and effective with public support. Different stakeholders, environmentalists, and experts should participate in inventory exercise without fear.

Caution about choice of exotic species: One harsh reality about forests is that man can plant trees, but cannot create a native forest. In the Modhupur sal forest area, native vegetation had been cleared for planting exotic ones such as rubber, acacia and eucalyptus. External resources played an important role in it. While eucalyptus plantation was stopped after the first rotation of plantation, acacia continued in the second rotation that started around 2002. The invasive acacia remains to be a dominant species in plantation to date. For the sake of creating some forests, which is difficult indeed, local species — sal and others — must be preferred. In plantation efforts, seeds of local species must be fully utilised from the next season. The forest professionals including those in the Forest Department say, ‘complex’ or mixed plantation must be preferred to ‘simple’ or monoculture plantation.

Protection of Adivasis:

The Garos and the Koch are the original inhabitants of the Modhupur forest. Their traditional rights over highland need to be recognised. What the authority says overtly about their protection and that of the forest, must be materialised concretely. The Adivasi communities cannot survive without state protection. If they are protected, the forests are better managed.

by admin | Jun 5, 2007 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain writes about the Forest Department’s ruinous campaign against the Garo banana plantations in Modhupur

As we entered the Garo village of Sainamari in the early morning of February 21, it was glistening with golden sunlight. But we were shocked to see that all the banana plants on both sides of the mud road through the village were cut and left lying there. As we approached the people of the village we saw that they were frightened of us, the strangers.

When we wanted to know what happened to the banana gardens of this huge village with some 400 Garo families, one of them, John Marak (55), led us to his house that stands in the eastern corner of his banana garden. Johh Marak is a retired BDR nayek (para-military personnel).

It is an unbelievable scene. He has six acres of banana gardens around his homestead. All his banana plants, except for some with bunches of mature banana, have just been chopped down. The Forest Department (FD) engaged scores of labourers to chop down his banana plants on February 15. He once had a pineapple garden and some 200 jackfruit trees on this land that he converted to a banana garden in the hope of a quick cash return. Some years ago, he cut all his jackfruits trees and sold them for cash to invest in the banana garden. He also invested Tk 290,000 ($4,000), that he got upon retirement, in banana gardening and constructing a large house. He watched helplessly from a distance as the FD cut down the banana trees. Given that the country is in a state of emergency and that the FD was assisted by the authorities, nobody could think of attempting any resistance.

Like John Marak, the entire village watched with great despair while their banana gardens were destroyed. “I received no notice before they cut my banana trees. No one discussed the matter with me.

They just suddenly came and cut them,” said Marak.

Two sisters from another Garo family in Sainamari, Beauty Nokorek (28) and Shagorika Nokorek (25), own 15 acres of land. They grow bananas on 12 acres to the west and east of their house. On February 15, in a matter of moments, hired workers from the Forest Department chopped down their entire banana crop. “We did not get a chance to say a word. Everything was destroyed before we could speak. They only left a few plants that had mature bananas on them,” said helpless Beauty Nokorek. These hard-working sisters cultivated this crop. Now that it has been destroyed, they will suffer a financial loss of some Tk 700,000 ($10,000). Like Shagorika and Beauty, another Garo woman, Nironi Simsang (40), cried in her three acre banana garden. Nironi’s two mud houses lie empty near her destroyed banana garden. She used to have 3,500 banana trees in this plot of hers, and from those she would earn around Tk 300,000 ($4,300).

The same scene plagues all of Sainamari, a century-old forest village of the Garos, one of the small ethnic communities of Bangladesh. All the banana plants were indiscriminately cut. In the hope of earning a quick profit, most of the Garo families of this village had cleared their gardens of pineapple, mango, jackfruit and lemon trees, and replaced them with banana.

With all the banana trees cut down, Sainamari village is no longer recognizable as a Garo habitation. Some years ago when I first came to this village I was enchanted by it. Every house was covered in greenery. There were many varieties of trees, vegetables, and pineapple and lemon gardens everywhere. This was the characteristic of the forest villages of the Garos, the first in the Modhupur sal forest. It is because of the invasion of banana that most villages like Sainamari have lost their characteristics.

On February 13, 14 and 15 (2007), the FD carried out the first round of its banana eviction raid. FD officers said that on these three days the FD chopped down banana plants on some 1,500 acres in and around Sainamari, Pegamari, Thanarbaid, Atashbari, Bhutia and Chunia — all of which are Garo villages. The Garos here were terrified. They have been living here for generations, and now they feel seriously threatened. The FD alleges that the banana gardens they cut down were all on FD land and were, therefore, illegal. They allege that politically powerful and locally influential Bengalis are the main players in, and beneficiaries of, banana cultivation. According to FD sources, these people used the Garos to facilitate wholesale banana cultivation. The FD said that they were unable to take action against illegal cultivators because of these powerful actors and interest groups. The state of emergency gave them the opportunity to stop banana cultivation and recover forestland.

The first target in the banana garden eviction program was Dhokhola Beat of Dhokhola Range. The villages mentioned above fall within this beat. The Dhokhola Range officer declared that the eviction action began with the big plots of a few Bengalis.

As we traveled around Sainamari and spoke to many Garos, it turned out that although some names of Bengalis surfaced, it is the Garo families that are facing the brunt of the eviction drive. The Modhupur sal forest was once the territory of the king of Natore, and the forest-dwelling Garo and Koch of Modhupur have resided in this forest for hundreds of years. They do have legal documents of ownership of the lowland (baid), but they do not have titles for most of the high land (chala) on which they have their homesteads and gardens. Marak, Shagorika, Beauty, Nironi — all these Garo individuals said they had no documents for their homes or gardens — these are all khas or government lands. According to the government gazette of recent times, all this land falls within a reserved forest.

As we traveled around Sainamari and spoke to many Garos, it turned out that although some names of Bengalis surfaced, it is the Garo families that are facing the brunt of the eviction drive. The Modhupur sal forest was once the territory of the king of Natore, and the forest-dwelling Garo and Koch of Modhupur have resided in this forest for hundreds of years. They do have legal documents of ownership of the lowland (baid), but they do not have titles for most of the high land (chala) on which they have their homesteads and gardens. Marak, Shagorika, Beauty, Nironi — all these Garo individuals said they had no documents for their homes or gardens — these are all khas or government lands. According to the government gazette of recent times, all this land falls within a reserved forest.

This makes the Garos afraid.

Most of those in Sainamari we spoke to said that their forefathers had lived in this village for the past 200 years. Because of this, they have an ancestral right to this land. This is the norm for forest-dwelling communities. They believe that under the pretext of evicting banana cultivators, the FD aims to take away their traditional rights to this land.

The Garos of Sainamari allege that the Forest Department targeted the Garo villages first, instead of going after the outsiders who established massive banana plantations by cutting large portions of forest. This is a major injustice to them.

When the FD began destroying the banana gardens, some people stepped forward and asked for more time so that they could harvest banana that would mature in a few days or weeks. The FD said that these gardens were illegally established and now the forest land would be brought under social forestry programs.

The Forest Department tried to appease the Garo people by saying that they would be the participants in the social forestry programs that would take place and that they would be the beneficiaries of social forestry.

This does not satisfy the Garos. “The Forest Department wants to include us in social forestry programs. But we want our traditional rights to land recognized,” says Garo leader Ajoy Mree.

The Garo people have many fears about social forestry programs. In Modhupur, “social forestry” began in 1989-90 through Asia Development Bank (ADB) funded Thana Afforestation and Nursery Development Project (TANDP). What people saw under the so-called “social forestry” — woodlot for production of fuel-wood and agro-forestry — were actually artificial forests or monoculture plantation.

When social forestry began, it came under criticism from Garos and environmentalists. People in Modhupur witnessed that the native forests were indiscriminately cut to establish plantation, sugarcoated as “social forestry.” After the first rotation of plantation was harvested or pillaged by forest thieves, the second rotation occurred under the Asia Development Bank’s Forestry Sector Project (FSP).

The destruction of hundreds of native species, the invasion of exotic species (acacia and eucalyptus), land remaining clear of plant species between rotations, etc., provided perfect ground to banana cultivators and land grabbers.

To the Garos, environmentalists, and residents of the area, plantations sugarcoated as social forestry brings no solution. That is why, when the FD speaks of social forestry, the Garos are not appeased. Another great fear is that if social forestry occurs they will lose their ancestral rights to their land. If this occurs, their traditional way of life will also be ruined.

After the first round of chopping, the Forest Department cut 650 acres of banana gardens on February 22. On this day, the targets were also Garo villages — Jangalia, Getchua, Beribaid and Magontinagar. The order apparently came from a high-up of the government. Traumatized, the Garos appealed to the government authorities. In response, an order came from the government to stop chopping banana plants. The secretary of the Ministry of Environment and Forests visited Modhupur, had a meeting with the Garos and then gave them his word that no more banana trees would be cut. However, according to sources from the Garo community, the secretary cautioned that further expansion of banana plantations would not be allowed on forestland, and that after the mature bananas were harvested further banana cultivation would not be allowed.

After the first round of chopping, the Forest Department cut 650 acres of banana gardens on February 22. On this day, the targets were also Garo villages — Jangalia, Getchua, Beribaid and Magontinagar. The order apparently came from a high-up of the government. Traumatized, the Garos appealed to the government authorities. In response, an order came from the government to stop chopping banana plants. The secretary of the Ministry of Environment and Forests visited Modhupur, had a meeting with the Garos and then gave them his word that no more banana trees would be cut. However, according to sources from the Garo community, the secretary cautioned that further expansion of banana plantations would not be allowed on forestland, and that after the mature bananas were harvested further banana cultivation would not be allowed.

The Forest Department sources said that in its raid against banana cultivation on forestland, equally harmful banana gardens in social forestry plots were not targeted. Papaya gardens, also on large areas of forestland, were not targeted. These are controlled by the outsiders, the real marauders on the forestland. Many, thus, raise the question why the FD targeted the Garo villages and not the large banana and papaya plots illegally established on the forestland.

There are many questions regarding the quality of social forestry. Even some FD officials express their concern over the selection of species to be planted under social forestry. They admit that they do not want exotic species such as acacia and eucalyptus, and want to bring back the native species lost because of plantation. However, they also claim that banana cultivation has ruined the soil to such a great extent in a short period of time that they see no other better alternative but to plant rapidly growing tree species such as acacia.

There are also allegations that in its raid against illegal banana cultivation the Forest Department has cut banana plants in some recorded lands of the Garos. From the beginning of the raid against banana, the Garos have been appealing to the government requesting for time to harvest the crop.

After the latest raid, on March 7, the government has given them time. But the locals are obliged to voluntarily stop banana cultivation on the forestland after harvesting. In a meeting at Dokhola Range on March 9, forest and environment adviser to the caretaker government, Dr. C.S. Karim, formed a 12-member committee including the Garos, and sought suggestions from the committee as regards eco-park, protection of sal forest, land use practices, etc. He visited some Garo villages and assured them that no arbitrary action would be taken against them.

Philip Gain is a director of a non-profit environmental and human rights organization.

by admin | Feb 10, 2006 | Newspaper Report

Adivasis in the capital by Philip Gain, published in the 15th Anniversary Special of The Daily Star, February 10, 2006.

Dashami Mree (20), a Mandi (Garo) girl from Modhupur, has chosen to become a professional beautician. Currently she works at Shahi’s Beauty Parlour at Salimullah Road in Mohammadpur area. A Mandi family from Chunia, a Mandi village in the Modhupur forests, owns the beauty parlour that it bought from a Bengalee owner more than five years back. The parlour is small but nicely decorated with big glasses and a row of front-line Bombay film actresses above the head. Dashami and half a dozen Mandi girls just fit in there. Dashami, compelled to leave her village due to her parents’ inability to meet her school expenses, finds her job as a beautician quite comfortable.

Dashami and three other Mandi girls working at the same parlour, live with the Mandi family that owns it. They live close to the parlour. They buy groceries themselves, cook meals for the whole family, eat together and socialise with the nearby Mandi families on a regular basis. This makes their social life vibrant and full of fun.

The beauty parlour was Dashami’s entry gate to Dhaka in 2003. She trained herself for six months [with the help of World Vision, a Christian NGO] in cutting hair, facial massage, plucking eyebrows, and all other parlour works. After training for six months she ventured into a few other parlours in Bogra and Sylhet before she came back to Shahi’s in the middle of 2005. With accommodation and food free, she gets a cash of Tk.500 (five hundred) per month. She was offered Tk.2,000 plus free accommodation and food in another parlour in Mirpur. But she chose to stick to a Mandi family although the cash she gets is small. This makes her stay in Dhaka secure and comfortable for now. She hopes to learn a few other things at Shahi’s and then look for better pay here or elsewhere.

Dashami is one of around 1,200 Mandi girls who work at some 400 beauty parlours in Dhaka city. An owner of a beauty parlour aims at employing maximum number of Mandi girls. The biggest of all the beauty parlours in Dhaka is Persona employing a few hundred Mandi girls in its two parlours.

The Mandi girls come from scores of Mandi villages of different districts in the north-central plains of Bangladesh. There is hardly any girl from any other Adivasi community such as the Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Hajong among others to be found in any beauty parlour. To the Mandi girls, who enjoy equal status with men in their matrilineal society, work in a beauty parlour is quite acceptable. According to Ranjit Ruga who runs Shahi’s, a skilled Mandi girl earns up to Tk.20,000 (twenty thousand) a month.

The Mandi girls work in beauty parlours on their choice and without any sense of moral degeneration. Some of them have married Bengalee owners at work place and are doing fine in their business. They are really straight in their business. They travel in the capital city with an air of freedom that most other women don’t enjoy. Not that they have no fear, but they look into your eyes without hesitation. They treat men as their equals. Mandi girls working in the beauty parlours or elsewhere in the city do not go unnoticed. Despite their distress back in the villages that bring them to cities to become beauticians, they are confident and enterprising.

As I was visiting Shahi’s to see Dashami’s work environment, I met with Kashuri Chisim, aged 38. She was paying a casual visit to the beauty parlour. It is typical of the Mandis in villages, in Dhaka city or elsewhere that they socialise with each other frequently and without notice, a trait of their kinship. Kashuri is a housemaid working in different houses of foreigners who come to Dhaka to work in foreign missions or international NGOs. As I exchanged a few words with her at Shahi’s, I got interested in visiting her home; she was actually heading for it. I was joined by Ranjit Ruga and his wife Tuliowners of Shahi’s Beauty Parlour.

We walked to Kashuri’s house. Kashuri has husband and three daughters. The elderly two daughters go to Holy Cross School–one in class eight and the other in class three. Kashuri’s husband Suman Marak (50) was sitting in the drawing room of their two-room quarter. The drawing room was filled with smoke from his cigarette. The smoke that I did not like eventually subsided. We had our warm conversation. The family of Kashuri and Suman, who come from Askipara in Haluaghat, have been living in Dhaka for 15 years now. During this period Kashuri spent two years in Saudi Arabia with her employer who took her there from Dhaka. Now Kashuri works in four houses and all her employers are foreigners. She works part-time in all these houses–two to three hours in maximum two houses a day, which means she works four to five hours a day. She earns around Tk.10,000 a month. Her husband, also working in houses, earns about that much. This family likes work like that. Then they have plenty of time to take care of their children. They can drop and pick up their daughters from school themselves.

“In the houses of the foreigners, it is primarily the Mandis who work as housemaids. The foreigners trust them very much. You will hardly see Bengalee women in the houses of the foreigners,” says Kashuri. While women work as housemaids in the houses of the foreigners, many Mandi men work as guards in the houses, diplomatic missions and offices. There are also a big number of Mandi men and women working in the houses of Bengalees. In Dhaka, many people would prefer a Mandi housemaid to others. They are trusted and reliable.

There are, of course, girls and women from other ethnic communities such as the Santal and Oraon who work in houses. But one will hardly find a Chakma, Tripura, Monipuri or Khasi who would be interested in household work.

The presence of the Mandis in Dhaka is unique. Thanks largely to Christianity, back in the villages, the literacy rate among them would be as high as 90%. Universal literacy among them certainly makes it easier for them to step out of the villages in search of fortune in Dhaka and other nearby cities. However, dispossession of local resources, deprivation and unemployment are some of the obvious underlying factors for their migration to cities.

Not only for work, the Mandi youths have a strong urge to come to Dhaka for higher education. “I prefer Dhaka to Mymensingh or Modhupur for my higher education. I understand what life is like in Dhaka city. In Dhaka I have greater chance to learn many things,” says Tutul Mree, a Mandi girl from Modhupur who is studying BA at Eden College. According to Tutul, there are some 50 Adivasi girls at Eden College and half of them are Mandis.

It is not just the Mandis, the other major ethnic communities of Bangladesh such as the Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Monipuri, Khasi, Santal, and Oraon also look towards Dhaka for higher education and exposure to the outside world.

Mandis in Dhaka are also seen in other areas such as hospitals, physiotherapy centres , garments, driving, Dhaka Export Processing Zone (DEPZ), NGOs, church enterprises, and mechanical workshops. One striking thing about the Mandis and members of other major ethnic communities in Dhaka is that they are hardly seen as rickshaw-pullers, salesman at shops, kulis or vendors in a market place, and in other similar jobs. One special feature about the Mandis and Adivasis in Dhaka is that they neither belong to the upper income class, nor the very low level. They stay in the middle and always opt for a decent life, though not economically very prosperous.

The largest number of individuals from an Adivasi community in the capital city is obviously the Mandis. There exists no reliable data. But what can be figured from different estimates is that their number in Dhaka city and its outskirts would vary between 10,000 to 12,000. While the Mandis are seen everywhere in Dhaka city, their main concentration is in Kalachanpur with about fifty percent of them living there.

The second largest ethnic community in Dhaka city and its outskirts must be the Chakmas with distinct characteristics. Like the Mandis there is also no reliable data on the number of the Chakmas and members of other ethnic communities from the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Different sources mention different figures. What is made out from these numbers is that the Chakmas in Dhaka city, DEPZ in Savar and Kanchpur would range between five and six thousand. According to a source, the number of Marmas would be some 500 and the Tripuras 200. The numbers of Tanchangya, Lushai, Pangkhua and other smaller ethnic communities are very small.