by admin | Jun 8, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | News Link

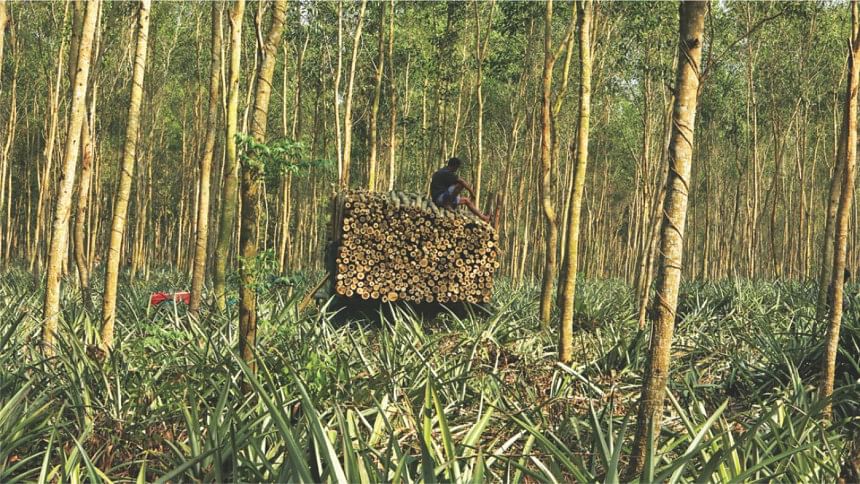

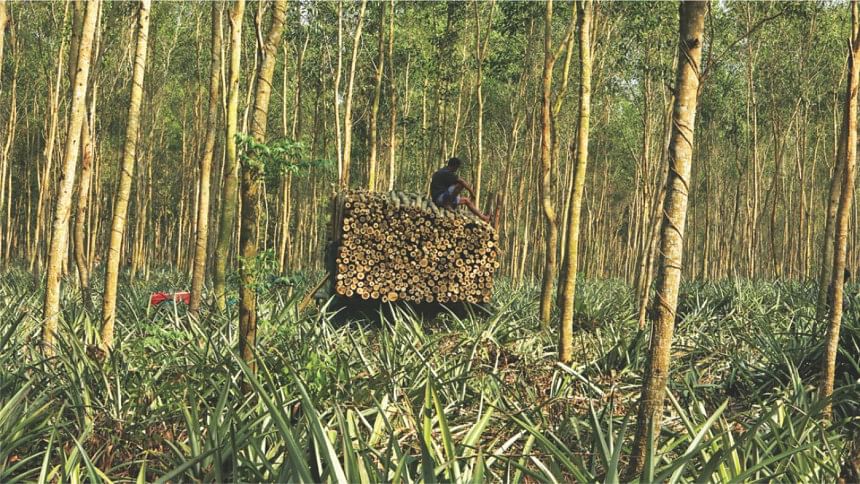

Rubber plantation in place of sal forest. Photo: Philip Gain

Sicilia Snal, aged 25 in 2006, was shot when she went to collect firewood in the forest near her village. Sicilia is a Garo woman of Uttar Rasulpur, in Madhupur sal forest area. It was early in the morning of August 21, 2006, that Sicilia went to collect firewood with a few other Garo women. On their way back, they put down their loads to take rest for a while. All of a sudden, to their great surprise, the forest guards fired shots from their guns. Sicilia was hit. She fell to the ground, unconscious and bleeding. Terrified all but one woman fled.

Then other villagers came to her rescue. She was immediately taken to Mymensingh Medical Hospital where she had a crude surgery and her gall bladder, plastered with many pellets, was removed. Some pellets remained in her kidney and around 100 pellets in the back of her body and hands—she has to live with these for the rest of her life.

Eleven years have passed since she was shot. The local Garos staged some protests and small humanitarian aid came to her family immediately after the assault. A case was also filed on her behalf. But the forest guards who fired the gun shots were never brought to justice. Nobody seriously moved with the case either.

Sicillia and other Garo women still go to the forests, their ancestral land, to collect firewood. Asked about the state of the case filed on her behalf Sicilia says in great frustration, “I know nothing about the case.” She believes the Forest Department and the Forest Guards are immune from legal action.

Before and after Sicilia was shot, a few killings and abuse of forestland in Madhupur made headlines in national and international newspapers. Notable among them was the killing of Piren Snal that left the Garos in terror. On January 3, 2004, the Garos organised a peaceful rally to evince their disdain against the so-called eco-park within the Madhupur National Park. While the Forest Department was desperate about fencing an area with concrete walls to demarcate the eco-park, the Garos saw it as a threat and an attempt to restrict their free movement in the forest they consider as their ancestral land.

The forest guards, with support from other security agencies, fired shots from their guns to disperse the rally. Hit by bullets, Piren Snal, a 28-year Garo youth from Joynagachha village, died on the spot. Utpol Nokrek, an 18-year youth then, was shot from the back, right into the spine that sent him to a wheel chair for the rest of his life.

The Madhupur sal forest is just one hotspot of abuses inflicted on forest villagers. The Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) is a vast forest landscape of Bangladesh that demonstrates serious abuses of all kinds done to the forest and forest people. Let me give the example of a small Chak forest village in Bandarban—and how the Chaks were eventually evicted from it.

It was in December 2008 that I first went to Badurjhiri, in Naikhongchhari upazila in Bandarban, which was, at the time, inhabited by 15 Chak families. Distinct from other ethnic communities in Bangladesh, this tiny Chak community lived for centuries in remote forest villages, satisfied with their traditional jum agriculture. Guided by a group of Chak men, we walked three and a half hours from Baishari Chak paras (hamlets) in Naikhongchhari upazila to reach Badurjhiri.

There had always been fears about invasion by Bangalees attracted to the land’s forest produce and encroachment of rubber and tobacco plantations by them, but Badurjhiri remained vibrant nonetheless, with crops that came from jum, pigs, fowls, and a rich variety of vegetables.

Going back to Badurjhiri in December 2010 was something of a shock. The rubber cultivators had expanded their boundaries towards Badurjhiri. The Chak men and women we walked with explained how the jungle continued to be cleared for rubber cultivation. In 2008, when we were passing through Amrajhiri, the jungle was being cleared in preparation for fresh rubber plantation. The nearby hills in the east, west, and south still had coverage of native forests. Two years later, we found out that the entire area had been cleared.

Commercial tobacco cultivation in Naikhhongchhari that is destructive for the forest. Photos: Philip Gain

Rubber cultivation was fast taking over their village, and the Chaks were afraid of what awaited them. They had witnessed how rubber plantation, among other reasons, had forced the Chaks of the neighbouring Longodujhiri (Khal) Chak Para to abandon their village. A Thoai Ching Chak, a villager, remarked, “If rubber cultivation spreads close to our village, we will surely be evicted.” He perhaps did not imagine that his fear would come true so soon.

They had to desert their village in April 2013.

Before the eviction, every time I would go to Badurjhiri, a group of Chak men and women would accompany me, but when I went back in 2013, they refused to go there. They told me horrific stories of attacks on them. On the night of March 19, 2013 the whole village was attacked by armed assailants in the dead of the night. For hours they stabbed and beat men and women, vandalised houses, slaughtered chickens (and loaded them in sacks), and looted belongings.

After the deadly attack, young girls and the wounded immediately left Badurjhiri. In April, almost all of the Chaks of Badurjhiri deserted the village. The 15 Chak families of Badurjhiri took shelter in four Chak villages in Baishari. They still live there.

Abuse, ill treatment and underlying factors

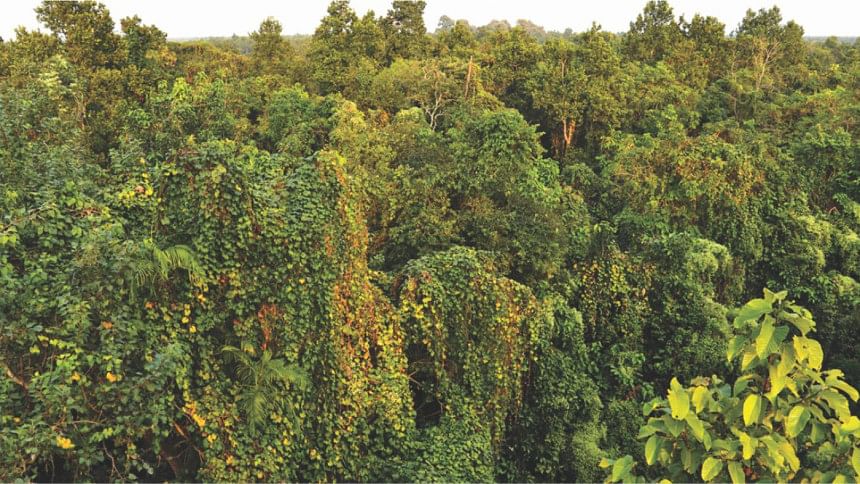

Abuses and ill treatment of the forest people—in Madhupur, Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), Khasi hamlets or other sal forest areas—are mere symptoms of underlying factors that have brought the forest to ruin. Officially, 18 percent of the country (2.6 million hectares) is public forestland—landmass recorded as forestland when the Forest Act of 1927 came into being. But in reality, approximately 6 percent is said to be covered by forests. This includes the mangroves and plantations covering 403,458 hectares since 1873. According to the Forest Department estimate, it now controls only 10.3 percent of the land surface (Forest Department 2001).

The largest category of forests in Bangladesh is reserved forests, which include the Sundarbans in the southwest (601,700ha), and forests in the CHT region in the southeast (322,331ha) and the Madhupur tracts in the north-central region (17,107ha). A much smaller category is the protected forests. Privately owned forests are another category, which range from plantations to those that are wholly owned by private individuals or companies. The last category of forests is unclassed state forests (USF), most of which is in the CHT.

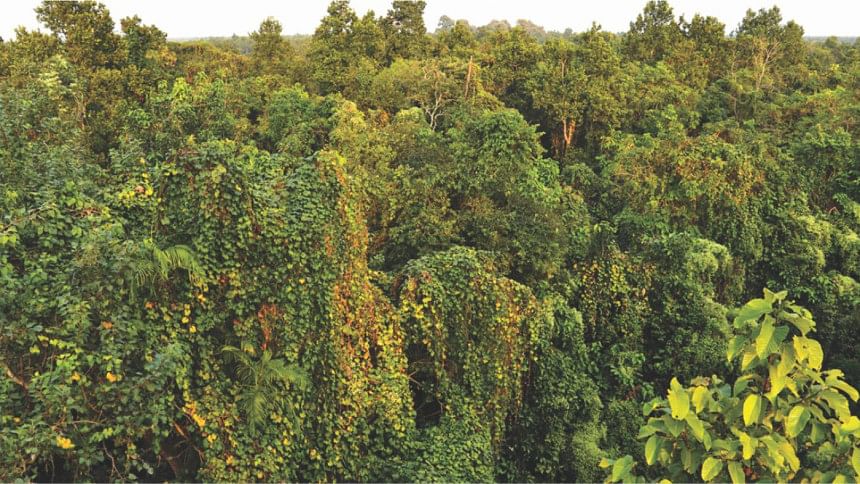

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

The relationship between people living in and around the forests is intimate—reciprocal and spiritual. The life and culture of the forest communities centre around the forests and the forest ecology. Their sustenance is dependent on the forest and therefore they do what they can to protect it. They are the “children of the forest” in the truest sense. To them civilisation and culture are inexorably connected with land, ecology and nature. It wasn’t too long ago that most of the indigenous peoples of Bangladesh lived in forests. Many factors, including actions taken by the state, have led to the massive destruction of the forest, and dispossessed forest communities of their land.

Reservation of the forests, beginning in the days of British colonial rule, has greatly curbed the rights of different indigenous communities to the land and the forests. In the CHT, about a quarter of the land was declared reserved forest during the British colonial era, severely limiting access of the indigenous communities to the land that had been their commons for centuries. Reservation of forest continues to date.

The local communities consider the expansion of the reserved forests as an immoral act. It dispossesses them of the means of their livelihood, and does immense harm to biodiversity and to knowledge production about medicinal plants of the local indigenous communities. The expansion of reserved forests, mainly for plantations, financed by international financial institutions (IFIs) and donors, has further muddied the waters when it comes to questions about land and ecology in the CHT, Madhupur and elsewhere.

Monoculture plantation has been the single biggest threat to the native forests in the hills as well as in the plains, affecting the life and livelihood of the forest-dependent communities. Plantations in Bangladesh include pulpwood (in the CHT), rubber, agroforestry, woodlot (for the production of fuelwood), teak, pine, etc. It is mainly the Forest Department and Bangladesh Forest Industries Development Corporation (BFIDC) that carry out the plantations on public forestland, mostly in the CHT, Chittagong, Cox’s Bazar, Sylhet and the sal forests. The IFIs—ADB and World Bank—funded most of these recent plantations.

The negative multiplier effects of manmade forest or plantations are quite similar around the globe. This is best illustrated in the words of Patricia Marchak (in her book, Logging the Globe, 1995), a Canadian scholar: “Plantations are monoculture, and the lack of biodiversity is of concern. They typically have sparse canopies and so do not protect the land; they cause air temperatures to rise, and they deplete, rather than increase, the water-table. They are generally exotic to regions. While the initial planting may be free of natural pests and diseases, that situation will not last, and plantation regions may not be in the position to combat scourges yet to arrive.”

When we look at the plantations on our public forestland, Patricia Marchak’s contention begins to make sense. It is possible to plant trees but it is impossible to create a forest. Hundreds of species of trees and bushes and a large number of other vegetable species grow on the forest floor. The knowledge of the forest-dwelling communities, their traditions, culture, history, education are all part of the forest. And now, all this has been seriously affected.

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

The displacement of human communities is another consequence of a plantation economy. In the CHT, pulpwood and other industrial plantations (including rubber and tobacco) have displaced human communities (jumias in particular) who have lived in the forests for centuries. The eviction of the Chaks from Badurjhiri and Longodujhiri in Bandarban is a clear pointer to the effects of plantation on forest villagers.

Ecological damage caused by rubber plantation and the so-called social or community forestry on public forestland is another concern. Although a rubber plantation looks green, it is a desert for other plant species, birds and wildlife. It brings in some cash for the government and private entrepreneurs, and misery and trouble for the local communities.

Vast expanses of banana, pineapple, papaya and spice plantations that we see in Madhupur sal forest can have far-reaching effects on the soil, seeds, wildlife, and human health. The trade in chemical pesticides, fertilisers and hormones related to it is huge.

Plantations provide ample ground to land grabbers to illegally convert the forestland to agricultural land. And it is the rich, the influential and the outsiders who encroach upon forestlands in collusion with government agencies and political forces. Banana plantations, illegally established on a massive scale on the forestland in Madhupur, are an example of how the plantation economy gives outsiders an opportunity to encroach upon public forestland. It is primarily the rich and the politically influential who control banana cultivation and benefit from it.

Aside from the plantations carried out with foreign funds (both loans and grants), state-sponsored and aid-dependent ‘development’ initiatives from the Pakistan era have had devastating consequences for the land and forests in the CHT. During the Pakistan regime, two development interventions of the state, Karnaphuli Paper Mill (KPM) and the Kaptai Hydroelectric Project, were a matter of “national pride”. But the projects caused unprecedented ecological damage from the start and posed the biggest threat to the indigenous peoples of the hills and their economic, aesthetic, and political life.

Is there a fix?

It is in the best interests of the nation and its people that whatever is left of the native forests in Bangladesh is protected from the onslaught brought about by monoculture plantation and human greed. Given all the damage done to the forests since colonial times, a natural fix is difficult to come by. However, if there is any hope of protecting what little is left, all actors, particularly the government agencies and donors, must recognise the underlying factors that have ruined the forest(s), especially the plantation economy and development initiatives taking place on forestland.

The surviving forest patches of Bangladesh are still so rich that the seeds and coppices would easily regenerate a degraded forest. A mature sal tree in any sal forest patch, for example, produces thousands of seeds in a season alone which can be planted for its expansion.

Banana plantations that have ruined much of sal forests to the core. Photo: Philip Gain

The sal forests in Madhupur and elsewhere provide an environment conducive for hundreds of other species of plants and life forms to grow. Professor Salar Khan (late) who guided the National Herbarium for many years requested the Forest Department not to plant exotic species to create monoculture in a place home to hundreds of native species. He tried to convince the department that the consequence of single species plantation is the destruction of genetic resources that the sal forest had sustained. He was ignored. He consistently requested the Forest Department to protect the remaining sal forests and replant wherever possible. ADB’s withdrawal from funding any forestry project in Bangladesh since 2007 is evidence that Professor Salar Khan was right. The World Bank’s funding in the forestry sector is reportedly limited.

In the CHT a hill left untouched for some years becomes green with myriad native species. In an abandoned jum plot in the CHT, countless native species appear and spread throughout the plot only in a few years. But a hill, planted with teak, pulpwood or other industrial monoculture, is likely to be ruined. Plantation is a manmade disaster that needs to be prevented in any forestland that has a chance to regenerate. However, “complex” or mixed plantation can be an option in areas that are truly degraded. Even in that situation there is no need for exotic species; there is plenty of local species.

Wrongs done to the forests and forest-dwelling communities need to be righted if justice is to be done. For that to happen, both forest and forest-dependent communities must be given protection. We should not forget the warning of Chandi Prashad Bhatt who said: “Unless we find a framework in which forests and people can live together, one or the other will be destroyed.”

Philip Gain is a researcher and the director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Madhupur sal forest, the Chittagong Hill Tracts and forest people since 1986.

by admin | May 11, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | The Daily Star

The nonagenarian remembers what it was like to be a Garo before the forest dramatically disappeared from Madhupur and Christianity took over.

Dinesh Nokrek, in his nineties, is a Garo kamal in Dharati village of Madhupur forest in Tangail. In Garo society, kamal signifies a priest in the traditional Garo religion of Sangsarek—a vanishing tradition, as almost all Garo people have by now converted to Christianity. Nokrek, who often likes to announce that he is a hundred years old, is a kabiraj (village doctor) as well. He has a strange device, sim-ma-nia, to diagnose and treat diseases including cancer. It remains hung on the mud wall inside his living-cum-dining room, which is stuffed with everything from sacks of grain to utensils.

Nokrek has no hesitation in announcing that he is a very happy man in his conjugal life with his 70-year-old second wife Monikkha Rema, whom he married seven years ago. He spotted Rema, a widow in Sandhakura village of Sherpur district, and married her following the sangsarek ritual.

Happy in a truly remote village on the western edge of the Madhupur sal forest, which evinces no mark of the sal tree any more, Nokrek has a very interesting life story to tell, of a forest that has dramatically disappeared from Madhupur [and elsewhere].

Father to five sons and three daughters—all from his first marriage to wife Palshi Dalbot, who passed away 10 years ago—Nokrek says he was born in Gypsy Pahar (pahar meaning hills), two kilometres east of Kamalapur Railway Station in Dhaka, which he remembers was a low-lying land. “The British filled the low-lying area with mud,” recollects Nokrek “and developed Kamalapur Rail Station.”

At least 80 Garo families lived at Gypsy Pahar, recalls Nokrek. The area was then covered with sal forest and there were many tigers and bears around, reminisces Nokrek excitedly. “Jum (slash-and-burn) cultivation was the primary agricultural practice in Gypsy Pahar, under the jurisdiction of the king of Natore,” he recalls. “We also practised limited plough agriculture.”

The hunting of pigs with spears was common, “but we were not allowed to kill deer and peacocks,” says Nokrek.

In Gypsy Pahar, all Garo families were sangsarek in contrast to today’s Garo society, in which Christianity is the dominant faith.

“The worst experiences in Gypsy Pahar were the encounters with tigers that were everyday events,” exclaims Nokrek. There is hardly anyone in Madhupur who knows that the Garo families came to the villages of Madhupur forest from distant locations such as today’s Kamalapur in Dhaka. This carries a significant message—the Garo are a hill and forest dwelling people. The sal forest, now miserably fragmented, extended up to Comilla and the traces of the Garo people around Kamalapur—before the station came into existence—is a significant mark in the history of migration of the Garo.

Dinesh Nokrek does not recall the exact year when his father moved out of Gypsy Pahar and came to Nalia in Ghatail. Actually, all Garo families in Gypsy Pahar, according to Nokrek, moved back north over a number of years. One landmark for Nokrek’s family is the big riot of 1964.

“My father, along with many other Mandis, moved to Nalia in Ghatiail 10 to 15 years before the big riot,” Dinesh explains. “I was very young then.”

Nalia was a kind of transit area before his father moved to Madhupur, then a dense forest with sparse Garo houses. “We lived hardly eight years in Nalia and some years in Mohishmari before moving to Madhupur, where we first landed in Dokhola and then went to Bagadoba,” Nokrek says.

“We left different forest areas mainly due to tigers and bears. But upon coming to Madhupur, we found the forest even more tiger-infested,” Nokrek recounts. “We used to encounter tigers every day and one year I killed two of them with a gun.”

It is from Bagadoba that Nokrek went to his wife’s house. Unlike other young men, it was quite a hard deal for him to settle in his wife’s family.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

In the young Nokrek’s case, his parents had delayed serving dinner to their son. Hungry, Nokrek sat to eat late in the evening and it was then that one of the captors entered the dining room and jumped him from behind.

“Manjok (captured)!” shouted the capturer to the others waiting outside. “Ribarembo (come quickly)!” The story still excites Nokrek. “Six strong men captured me. Each of them held different parts of my body and I was helpless,” says Nokrek, smiling wistfully. As they were marching with their hapless capture, they shouted “Man-ba-jok (We are coming with the son-in-law)!” From Bagadoba, Nokrek was taken to the neighbouring Dublakuri village in Jamalpur district.

Nokrek was married off soon after he was brought to the bride’s house. Such quick marriages following the traditional custom are called ‘murgichira bia’. A dinner of fowls was then served to the starving Nokrek.

Dinesh Nokrek explaining the power of sim-ma-nia. Photo: Philip Gain

Married at 28, Nokrek was not happy with his wife’s family because they were not well off. He spent the night quietly and fled to his parents’ house the next morning.

“I wanted to abandon my wife, so I stayed a year at my father’s house,” recalls Nokrek. “But then the village leaders convinced me to return to my wife’s house.” A large pig was slaughtered and a celebration followed.

With his wife, Nokrek moved back to Bagadoba from Dublakuri seven years into their marriage. They lived there till 1988, when they moved to Dharati—Nokrek’s current village.

Today, Dharati is a mixed village with 155 Garo households and 124 Bengali households. Rubber plantations flank the village on either side and banana, pineapple, ginger, turmeric and other cash crops cover the entire village. The 8,000-acre sal forest was ruthlessly cleared to plant rubber trees. Still considered a forest, the land was transferred to the Bangladesh Forest Industry Development Corporation (BFIDC) for production of rubber.

Like other Garo villages, all but Dinesh Nokrek and a few others are Christians in Dharati. In his family, only Nokrek is Sangsarek. His sons and daughters are Christians. His second wife, always smiling, pretends to be Sangsarek to make Nokrek happy. She was Christian before coming to his family. Nokrek himself is open-minded about Christianity.

Like Dinesh, most of the elderly Garo people of the forest villages in Madhupur tell stunning stories of their migrations, the celebration of Christianity in Garo villages, the destruction of the forest and the factors that underpinned various other changes. Unlike in the past, they are now settled in their villages. Yet, some move to cities in search of jobs and income. The Garo in the capital today, approximately 15 percent of its total population of around one lakh, speaks to the transformation of the Garo community, as a result of Christianity and the spread of education.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Madhupur sal forest and its people since 1986.

by admin | Apr 30, 2018 | Newspaper Report

by Philip Gain, Dhaka Tribune, April 30th, 2018

Hemlata Bauri (65) earns tk 60 for a full day’s work at Daluchhera Tea Garden in Fenchuganj upazila, Sylhet district. She is paid a daily wage, so she does not get a weekly holiday. If she opts to work on a public holiday, she only gets Tk 30 for it. For these wages, she has to reach a nirikh (daily quota) of 20 kgs of tealeaves to qualify for the daily cash payment – hard work under the heat of the midday sun in the hilly tea garden terrains of Sylhet. Bauri has been a tea worker for nearly 50 years now. She became a ‘registered worker’ many years after she joined, but she has never been issued an appointment letter, which the owner is compelled to issue according to labour law. The workers of this tea garden are not members of the Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union (BCSU), the only trade union for around 160 tea gardens that have around 122,000 workers. It is also the largest trade union in the country. Daluchhera Tea Estate, one of 19 tea gardens in Sylhet district, is a small garden with 34 registered and 15 casual workers. It is a ‘C’ class garden, which means its production capacity is less than that of ‘A’ and ‘B’ class gardens. Our recent investigation shows unprecedented irregularities in wage payment at Daluchhera. The chairman of the panchayet of the tea garden, Barma Turia, informed us that “wages here was Tk30 even four years ago.” The workers of the garden demanded a pay rise when wages in other gardens increased. The workers and the owners side sat together and determined the current daily cash pay of Tk60. However, a condition was imposed of a minimum of 12 hours of work a day. Turia informed us that workers end up working around eight hours a day instead.

Such cash pay is a clear breach of written agreement between the owners’ association and BCSU.

Rambhajan Kairi, the general secretary of BCSU reaffirmed, “Paying lower wages is not just a breach of agreement between the owner and workers, but also a violation of the Labour Law. The agreement was indeed made under the rubric of Labour Law 2006.” According to this agreement, daily cash payments for ‘C’ class gardens is Tk82 and, Tk85 and Tk83 for ‘A’ and ‘B’ class gardens respectively, effective from January 2015. The condition at Daluchhera is believed to be the worst in all the 160 tea gardens in the traditional tea growing five districts—Sylhet, Maulvibazar, Habiganj, Chittagong and the Rangamati Hill District. However, the conditions of tea workers and their communities, with a huge proportion of them generally being non-Bengali, is very different from other industrial workers in terms of their identities and access to justice as workers. The British companies, more than 150 years ago, brought these tea workers from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens in Sylhet region.

The misfortune of these indentured laborers started with their journey to the tea gardens.

According to one account, in the early years, a third of the tea plantation workers died during their long journey to the tea gardens and due to the tough work and living conditions. Upon arrival, these labourers received a new identity – that of coolie – and became property of the tea companies. These coolies, belonging to many ethnic identities, cleared jungles, planted and tended tea seedlings and saplings, planted shade trees, and built luxurious bungalows for tea planters. But they had their destiny tied to their huts in the “labor lines” that they built themselves.

Today, what is most concerning for the tea workers is their wages—daily or monthly.

The maximum daily cash pay for the daily rated worker in 2008 was Tk 32.50 (less than half a US$), which was raised to Tk 48.50 (US 63 cents) by the first ever minimum wage board assigned for the tea workers that went into effect from September 1, 2009. This was still a miserable pay that had severe effects on the daily life of tea workers. As a result of negotiations between the workers’ representatives and the owners mediated by the government, the daily cash pay of the tea workers was raised to Tk 69, which went into effect from June1, 2013.

The conditions of tea workers and their communities, with a huge proportion of them generally being non-Bengali, is very different from other industrial workers in terms of their identities and access to justice as workers

The current (2015) central committee of BCSU, in its latest agreement with the Bangladesh Tea Association, had been able to raise the daily cash pay to Tk 85 for A-class gardens, Tk 83 for B-class gardens and Tk 82 for C-class gardens. This new wage structure went into effect from January 2015.

It was also the first time in the history of the tea industry that workers began to get paid for weekly holidays (on Sunday).

It was also the first time that owners agreed to provide gratuity, which however, is not yet given in any garden. The excuse the owners use for such low pay is fringe benefits given to workers. The key fringe benefits include free housing and concessional rate of ration (rice/wheat) at Tk 2.00 per kg. A worker, on average, gets around seven kgs of food grains at concessional rate. The houses provided are basic. The workers are obviously very unhappy about these wages. “The current wages, Tk85 per day, are unjust. In the agreement that will be effective from January 2017, we will demand a daily cash pay of Tk230. It is still not enough, but we are demanding this in consideration of the overall situation,” says Rambhajan Kairi, who is leading on-going negotiations with the owners on behalf of the workers. “But the owners are proposing Tk95. This is very illogical and unjust. We will not accept it in any way.” “The owners are also not yet paying gratuity,” says Kairi, “which is a breach of our agreement.”

Confined to the tea gardens, tea workers are considered to modern-day slaves by many, and are one of the most vulnerable peoples of Bangladesh

Fringe benefits other than housing and rations include some allowances, attendance incentive, access to khet land for production of crop (those accessing such land have their rations slashed), medical care, provident fund, pension, etc.

The daily cash pay of a Bangladeshi tea worker is much lower than what a tea worker gets in Sri Lanka, which is around $4.5.

However, the cash pay of a tea worker in India is not a lot better than what the tea workers of Bangladesh have started to get from January 2015. Confined to the tea gardens, tea workers are considered to modern-day slaves by many, and are one of the most vulnerable peoples of Bangladesh. Into the fifth generation, they continue to remain socially excluded, low-paid, overwhelmingly illiterate, deprived and disconnected. They have also lost their original languages in most part, culture, history, education, knowledge and unity. Fearful of their future in an unknown country outside the tea gardens, the tea communities keep their voices down and stay content with the meagre amenities of life. As citizens of Bangladesh, they are free to live anywhere in the country. But the reality is that many of the members of the tea communities have never stepped out of the tea gardens.

An invisible chain keeps them tied to the tea gardens.

Social and economic exclusion, dispossession and the treatment they get from their managements and Bengali neighbours have rendered them ‘captive’ or ‘tied’ labourers. It is in this background that they deserve special attention of the state and the people of the majority community, not just equal treatment, which however, remains a far cry. Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing, filming, photographing the tea communities for more than a decade.

by admin | Apr 27, 2018 | Newspaper Report

Philip Gain | News Link

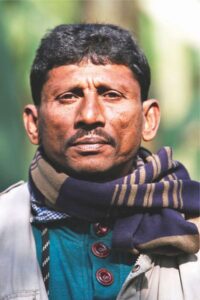

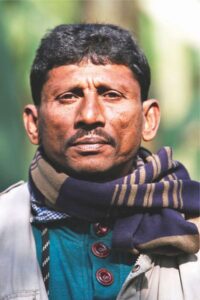

Hssan Ali appeared at Tangail Forest Court on January 4, 2018 to take bail in a ‘forest case’ (no. 405) that was filed in 1998 for felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.

Hasan Ali and his family of two wives, three daughters and two sons, are now permanent residents of Gachhabari village of Aronkhola union in Madhupur upazila. Nearly a hundred Bengali families settled in the part of Gachhabari village that eventually came to be known as Farm Para during the Pakistan era. Gachhabari, before the Bengali moved in, was a Garo village and the area was covered with pretty deep jungle. Today that has disappeared and natural vegetation is replaced by plantation of acacia, pineapple, papaya and spices.

Hasan Ali. Photo: Philip Gain

Ali has been appearing before Tangail Forest Court for this particular case along with others since 1998 and waited years to see whether he is charged or not. He has appeared before the court for just one case at least 60 times, and has served jail-time for approximately 14 months for 20 other cases. Since 1990, Ali has faced around 100 forest cases—35 of them settled, but not without penalties.

Ali does not know anyone who has faced so many cases in Madhupur. “Now I am facing more than 65 forest cases. On average I go to Tangail Forest Court nearly 10 days in a month,” reports Ali. “In the past, sometimes I would go to court every work day in a given week.”

Dealing with forest cases is an expensive affair. “For each case settled I have spent ar0und Tk 60,000,” says Ali. “So far I have spent around Tk 40 lakhs.”

Yet, Hasan Ali is one of the more financially secure ones facing forest cases. Ali’s monthly family income looks good at the village standard. “But every month I spend at least Tk 20,000 on cases,” he says, “and therefore I am always in debt.”

Ali is one of the thousands facing forest cases in Madhupur forest area. But in a number of cases he is exceptional. “The allegations the Forest Department (FD) makes in the forest cases are vague or false,” claims Ali. “Some of the allegations the FD made in forest cases against me and others are based on hearsay.”

“I have never been caught red-handed,” asserts Ali. Everyone of the accused that this writer interviewed concurs with Ali—they do not flatly deny that they never got engaged in cutting trees. But they report that the massive tree felling in the Madhupur sal forest started in the early 1990s, which coincides with the advent of social forestry.

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

Social Forestry in place of natural sal forest.

“It is the FD that engaged the tree-felling gangs to clear patches of sal forest. It was illegal. Then foreign trees (eucalyptus and acacia) were planted in place of sal and other local species,” alleges Ali. “We protested against such illegal deals, only to have the FD file forest cases against us.” The case in which Ali got bail on January 4, 2018 was one such case from 1998.

The act of such illicit deals came to be known as giving “line”. To set a “line”, the FD allegedly fixed an amount and allowed the wood cutters hired by “line” gangs to cut trees from certain areas.

There were locals who sometimes worked for these gangs, state the villagers. However, most of them were outsiders who were paid daily wages. “Then the same FD filed forest cases against us because we were seen felling trees, an act performed for the preparation of social forestry plantations,” says Ali.

Md Yunus Ali, who retired as Chief Conservator of Forest (CCF) on January 2017, refutes the allegation that social forestry was carried out clearing sal forest patches in many places. “Social forestry—woodlot and agroforestry—had been carried out only in places of forest land where there was no potential for regeneration of natural forest,” he argues.

Ali and others in the Madhupur forest villages, however, narrate a different story. The villagers say that little of the Madhupur sal forest survives today because of social forestry projects implemented by the Forest Department and funded by the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Very little of such natural forest remains in Modhupur today.

Ali and others—Garo and Bengali—who have been trying to rescue themselves from the web of forest cases hardly had any forest cases filed against them before social forestry began. “None of the cases filed against me are related to natural forests,” asserts Ali.

Social forestry was supposed to help local people. “The reality is just the opposite. It has been very harmful for locals and the environment,” laments Md. Ramjan Ali of Amlitala, a village in the middle of the Madhupur sal forest.

Ramjan reports that the first forest case filed against him was in 1996, when he was a student of class nine and away from home. Shocked and angered, he could not continue his studies. Twenty-eight cases were filed against him, of which 10 have been settled and 18 are still pending. Ramjan has so far been in Tangail Jail 11 times—from one week to 29 days.

For Ramjan Ali it has been a very high-priced affair to deal with forest cases. “For each case settled,” sighs Ramjan Ali, “I have spent around Tk 1 lakh. Lately I had to spend Tk 30,000 to take bail in just one case.”

“When cases were filed against a poor wage-earner, he had no other choice but to engage in further tree-felling activities to manage cash for running cases,” explains Ramjan Ali. “The forest cases are actually traps, which are beneficial for the FD, lawyers, police and others.”

Many, unable to manage cash, have either never appeared before the court or stopped showing up completely. They go into hiding with arrest warrants issued against them.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Harvest time of social forestry at the end of the first rotation. In this area sal forest was cleared for preparation of social forestry.

Jitendra Nokrek (48), a farmer and day-labourer of Joloi village, is one such Garo. Accused in four forest cases, he appeared before the forest court from 1993 up to 2000. He was also put into jail five times—the durations ranging from one week to 10 days. He sold 90 decimals of his land to run cases. “Then I stopped appearing before the court,” says Nokrek, “because I could not manage cash anymore.” The police are searching for him. “I cannot sleep in my house in peace. Sometimes I hide at night in other people’s houses.” Fed up, he has also thrown away the documents of forest cases.

Niren Nokrek (54), also from Joloi, does not know how many cases are there against him. “I have heard from others that there are forest cases against me. I never showed up in the court because they are expensive and never-ending.” says Niren furtively, while talking to this writer in a tea stall.

Niren and others claim that the FD files cases without any good reason. “Sometimes they file cases against names taken from the voter list,” alleges Niren.

Anyone can be a target of forest cases

The forest cases can be filed against anyone—respected Garo social leaders, school teachers and anyone who have, at different times, protested against the ‘misdeeds’ of the Forest Department, allege villagers.

One recent example of such forest cases involves Eugin Nokrek (53) of Gaira village, a traditional Garo village right in the heart of Madhupur National Park—a village that has existed there since long before the creation of the Forest Department and the national park. In the first of two cases from 2016, he is accused of land grabbing and attempting to establish a banana plantation and in the second he is accused of stealing and smuggling trees from the forest.

Eugin Nokrek, president of Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad, the most important social organisation of the Garo and Koch of Madhupur, believes the cases have been filed against him because of his activism. “I have been leading the resistance of the adivasis of the Madhupur forest. At the center of our movement is our land rights. We want our land and forest protected. The FD files false forest cases to keep us under pressure,” responds Nokrek.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

Turmeric plantation in place of sal that was.

There was one forest case against Eugin at the time of resistance against an eco-park in 2004. The case was later dismissed.

“The FD filed another case right after the visit of Shantu Larma, chairman of the CHT Regional Council, who came to Madhupur to express his solidarity with our movement,” reports Eugin. Shantu Larma visited Madhupur on September 22, 2016. The day before, Eugin claims, top-ranking local government officials accompanied Awami League’s Madhupur branch vice-chairman Yakub Ali to Eugin’s Jalchhatra office with a request to cancel Shantu Larma’s programme. “But we could not keep the request, which angered the FD and a case was filed against me,” alleges Eugin.

An FD official based in National Park Sadar (JAUS) Range of Madhupur forest, however, provides a conflicting version of events surrounding the forest cases filed against Eugin Nokrek, claiming the cases filed are well grounded. “Eugin Nokrek got a one-hectare plot of natural vegetation (sal coppices) under a co-management arrangement between the FD and the locals,” says the official. “Under such arrangement, the participants, Eugin being one of them, are supposed protect sal coppices and other species of natural vegetation. They will get a percentage of benefit for their time investment.”

He alleges that Eugin Nokrek allowed clearing a part of his plot and plantation of banana. “This is a serious offence, so we filed cases against him,” says the official who also adds that the FD wanted to amicably settle matter with Eugin Nokrek. “But he did not respond to our request and we had no alternative but to file cases.

This version that the forest official relayed to this writer does not match with the pleading made in the case document—which accuse Eugin of general tree felling.

There are many other community leaders and school teachers who are financially crushed due to forest cases. One such teacher is Nere Norbert of Gaira village, who actively participated in the resistance movement against the eco-park. The FD filed 12 cases against him between 2004 and 2008. “Nine of the cases filed against me have been settled in 14 years, at very high price—Tk 9 lakhs,” says Norbert.

Such a huge expenditure for cases has financially crippled Norbert, a father of six children. “The mental pressure for forest cases is immense,” says Norbert. “I have been falsely rendered plunderer of the very forest that we have always tried to protect.”

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

Harvest time of social forestry that signals end of native forest.

According to the Tangail Forest Court annual report from 2017, the number of forest cases pending action till December was 4,954, which in 2016 was 5,350. Of the cases pending in 2017, 2,236 had been taken into cognizance and 2,718 were under trial. The number of forest cases settled in 2017 was 626 and fresh cases filed during this year were 230.

Of 626 cases settled, 288 were settled after full court procedure. 175 people in 48 cases have been convicted, while 837 people have been acquitted in 240 cases. Cases settled without full trial and through other means were 338 and 968 accused have been acquitted in these cases.

The Forest Court in Tangail is the only court in the district to settle all forest cases. One special magistrate is assigned for this court. However, the forest court is functional only part-time—from 2:30 pm to 4:00 pm, five days a week.

The highest number of forest cases occurs in Madhupur, followed by Sakhipur, Mirzapur and Ghatail.

The Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), in its independent household survey in 44 villages, found 3,029 forest cases pending as of 2017.

The Bench clerk of Tangail Forest Court, Tapan Chowdhury, confirms that the forest cases filed in the court dramatically increased in 1991-1992, when natural forest patches were indiscriminately cut in favour of plantations. Most of the cases have been lingering in court.

On allegation that excessive forest cases were filed during the first decade of social forestry, Md Yunus Ali, however, says, “It is not true at all that forest cases were filed in excessive numbers during the initial stage or the first five years of social forestry.”

CFWs—’thieves’ become protectors!

The Forest Department created a troop of community forest workers widely known as CFWs to guard the forest that is on the brink of ruination. CFWs, in the eyes of the FD, were forest thieves and most of them face forest cases. The idea of turning the ‘forest thieves’ into protectors was brewed in the project, ‘Re-vegetation of Madhupur Forests through Rehabilitation of Forest Dependent Local and Ethnic Communities’ that started in July 2009. The CFWS were given incentives such as cash that came in different forms [though small] and promise of relief from forest cases. The CFWs appreciated cash pay to each of them for patrolling the forest to keep the remnants safe (!) from being stolen.

Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul, a former conservator of forest who served as DFO, Tangail and director of the USAID-funded project asserted that “Forest cases decreased significantly at my time (between 2011 to 2013) and filing of fresh forest cases in those years came down to almost nil, because crime decreased significantly.”

Hasan Ali and Ramjan Ali were two of 786 CFWs (according to the latest count). They remember Dr Ashit Ranjan Paul with gratitude. But CFWS are no more active and have stopped patrolling the forest. The prime factor is the funding for the project has stopped. “The false or fabricated forest cases against us have not been settled as promised,” complains Hasan Ali. Ramjan Ali and other victims of forest cases concur with Ali.

What Hasan Ali, Ramjan Ali and hundreds of other victims of forest cases realise is that no sympathy of one or two forest officials will help unless the systems and policies have changed and appropriate judicial measures have been taken.

Philip Gain is researcher and director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD). He has been reporting, writing and filming on Modhupur sal forest and its people since 1986.

Rabiullah, Probin Chisim and Sonjoy Kairi assisted the writer in gathering information from Tangail Forest Court.

by admin | Dec 20, 2015 | Newspaper Report

by Philip Gain, The Daily Star, December 20, 2015

Tea workers in an open-air protest rally against economic zone. Photo:Philip Gain

It was a very tense morning for Udoy Modi, a tea worker of Chandpore Tea Estate on December 15. In his sixties, Udoy wrapped his chest with the Bangladeshi flag and carried an arrow and a couple of bows. He sat stone-faced on the land that he was forced to protect from being taken away by the government.

Udoy was not alone. A dozen other men of the tea estate in Habiganj district appeared with bows and arrows to join a massive protest rally against the government’s plan to establish an economic zone on vast paddy lands in the northern part of the estate. It was harvest time and the vast field was covered with ripe paddy.

The open-air protest gathering was spontaneous. Hundreds of men and women, holding sticks, axes, placards, and bows and arrows in hand, had assembled at the paddy land owned by the British tea company, Duncan Brothers, while flying the Bangladeshi flag on their heads and wrapping them around their chests. By noon, a disciplined crowd filled the middle of the 511 acres of paddy land that the government transferred to the Bangladesh Economic Zone Authority (BEZA) on November 21, 2015 to establish an economic zone there.

BEZA, operating under the authority of the prime minister’s office, has an ambitious plan to establish 100 economic zones throughout the country to speed up economic growth. On December 12, the Chunarughat TNO office announced that government officials would visit the area the next day to demarcate the land for an economic zone. The TNO reportedly asked for help in demarcating the land with pillars. Instead, it was faced with one of the most unprecedented protests ever seen by tea garden workers.

From December 13, the tea workers of Chandpore Tea Estate stopped working in the tea garden and started assembling [from around 10 am till 4 pm] on the cropland, which in the tea garden’s terminology is known as khet land. Established in 1890, the tea estate is classified as an “A” class garden (to be in category “A” a garden needs to produce 181,000 kgs or more of tea per annum) with three fari (subsidiary) gardens — Begum Khan, Jualbhanga, and Ramgonga. The total grant land (public land leased for production of tea) of this garden is: 3,851 acres, of which paddy or khet land is 985 acres. Of this khet land, 511 acres are situated in the north of the garden, bisected by the old Dhaka-Sylhet highway, has been transferred to BEZA. The garden has 1,955 workers and a populace of 8,833 people.

The tea workers cut the jungle some 150 years ago, cleaned the bushes and reeds to make the tea gardens. At the same time, they prepared the land for growing crops. After the partition of India, the entire land for cultivating tea became public land. The tea communities (now with a population of around half a million) could not take advantage of the State Acquisition and Tenancy Act that awarded ownership of land to the users. It is because of exceptional land management that the tea workers and their communities cannot own land. But they have cultivated the khet land for generations.

Of the 113,663.87 ha grant land of the whole tea industry (except Panchagarh), 12,134.29 ha are paddy land. In official documents, the government has shown that the paddy land of the Chandpore Tea Estate transferred to BEZA is non-agricultural land. This has angered the tea workers.

“We will not give our khet land for the economic zone,” said Monsuk Urang (52) who we found harvesting his paddy on December 15, before joining the protest rally. “My father and grandfather cultivated this land. They cut the jungle, fought with wild animals and insects. We are ready to die but we will not give up this land.”

According to sources of the Chandpore Tea Estate, more than 1,000 families use the 511 acres of paddy land. Many of these families depend solely on this land for subsistence.

All of those who use khet land at the Chandpore Tea Estate share Monsuk Urang’s sentiments. Each day since December 15, the number of protesters has only been increasing. They begin the peaceful protest rally with the national anthem. They hold the national flag in one hand and placards with slogans such as, “My land, my mother, I will not allow it to be snatched away”, or “Resist attempts by those who want to take away the paddy lands.”

Officials of Duncan Brothers are concerned, as the tea estate has remained closed since December 13. “It is not yet season for massive production, yet we produce 3,000 kgs of tea per day. However, it is the time to prune the tea plants and perform other jobs to keep the garden in shape,” said Shamim Huda, Manager of the Chandpore Tea Estate.

It’s even worse for the workers. If they do not go to work, they are not paid for the day. Many have left their ripe paddy fields unharvested. They fear that if they do harvest the fields, the land will appear non-agricultural. “We are ready for any sacrifice, including giving blood to protect the paddy land,” said Swapon Santal, a leader of the Bhumi Raksha Committee (Land Protection Committee).

An appeal to the Prime Minister

The tea workers are extremely patriotic as could be seen from the national flags they hold close to their heart every day since the beginning of the protest movement. Many of them even actively participated in the Liberation War of 1971. They have complete trust in Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

The leaders of the Bhumi Raksha Committee are making all arrangements to meet the PM to ensure that she knows that the land transferred to EPZ is actually agricultural land. Even though they complain that the local administration attitude towards them has so far been aggressive and inhospitable, they believe wholeheartedly that the Prime Minister will not disappoint them.

Several protesters have even publicly announced that if the PM assures them that justice will be done to them, they will return home. “All we want is an open discussion,” they’ve stressed.

Officials of Duncan Brothers have told this writer that the lease of the Chandpore Tea Estate was last renewed in 2013, and the land now transferred was part of the tea garden. “But the government has neither communicated with us in writing nor called us for any meeting about the transfer of the paddy land to be used as an economic zone,” said a senior official of Duncan Brothers. “The government can take land granted for tea production for its use. But we sincerely expected the government to discuss the matter with us.”

The tea workers and the owner hold mostly similar views about the issue, even though the owners do not show up at the rally or publicly display support for the protest movement. Nevertheless, neither groups want the government to lie about the condition of the land. They want the PM to be made aware of the truth about the status of the khet land and offer a solution after considering the interests of all the parties involved.

Support has been pouring in from people belonging to different quarters for this non-violent protest movement. Everybody wants to see justice being done to these hardworking tea workers.

(Note: The tea workers had organised a protest rally from December 13 till December 18, until writing of this article. They were keen to intensify the protest movement, unless the government listens to their demands).

The writer is a researcher and Director of the Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD).

by admin | Jan 28, 2011 | Newspaper Report

The Chaks of Baishari are a tiny community, the existence of which is being threatened by encroachment of their land to grow rubber and tobacco, in the name of development. Story by Philip Gain. the daily STAR (stories behind the news) | Volume 10 | Issue 045 | January 28, 2011.

The Chaks of Baishari are a tiny community, the existence of which is being threatened by encroachment of their land to grow rubber and tobacco, in the name of development.

|

|

Chak woman in Badurjhiri. Photo: Philip Gain

|

It’s an exciting three-hour journey on foot from Baishari Chak Headmanpara to a real jungle village named Badurjhiri of 16 Chak families. On November 18, 2010, five of us–three Chaks and two of us from Dhaka–walk through the hills and streams, beauty and devastation with both joy and trepidation in our hearts.

As we walk out of the Chak paras (villages) in Baishari, the weather is calm and everything glistens under the golden sunlight of autumn. What fascinates the most as we walk through the Chak villages are the smiles of the Chaks and the look of the elderly women distinguished by their large earrings that stretch and distort their earlobes. Such large earrings and the wide earlobes are not to be found among women in any other ethnic community in Bangladesh. Another interesting scene is of the elderly women with tobacco pipes in their mouth blowing white smoke with an air of freedom.

One may wonder where these two strange places–Baishari and Badurjhiri–are. Both are located in Baishari Union in Naikhongchhari Upazila in Bandarban Hill District. Quite unknown even to regular trekkers to the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), Baishari is one of four unions in Naikhongchhari Upazila with Chak habitation. There are around 3,000 Chaks in Bangladesh and another four to five thousand in Myanmar. There is no confirmed record of these beautiful people anywhere else on the globe. Imagine just seven thousand people in the whole world who have a distinct language and lifestyle! They proudly speak their language among themselves and find no difficulty speaking when communicating with their Bengali neighbours. They also speak Marma; but the Marmas, their close neighbours cannot speak the language of the Chak.

Leaving the Baishari Chak villages behind we get into the coolness of nature. Our feet dip into the cool stream water flowing over narrow, sandy, and shallow yellowish bed. Where does the water come from? “The water flows from the roots of trees that still survive and hold water from the rains,” is my naïve response to the query of my companion from Dhaka as regards to the source of the crystal clear cooling waters.

Dhung Cha Aung Chak (47), our host and guide, tells us it will take roughly three hours to walk to Badurjhiri and cautions us that we will pass through risky elephant habitat. He advises us to stay watchful. We are tense.

|

|

Chak woman at jum in Baishari. Photo: Philip Gain

|

What shocks us shortly after leaving the Chak paras is the vast expanse of rubber monoculture beginning from the edge of the Chak villages and extending far into the southeast. From a distance its looks like a deep jungle. Mistake! As we walk through rows of rubber trees we feel it’s a pure monoculture and a death-knell to wildlife. The rubber tree is an exotic species in this area and everywhere else in Bangladesh. It is a “milking” tree to its cultivators–most of them outsiders–who make a fast buck out of its cultivation. But for the Chaks and the Marmas, this is a ‘bad development’ on their traditional land. What used to be native forests, jum land, and grounds for their hunting and gathering is now rubber plantation. Bamboo, once an important source of livelihood and found in abundance, has been completely exhausted. This area also used to be an important habitat for elephants. The elephants still survive but in conflict with humans. Tree houses near paddy fields serve to keep the elephants away.

As we move forward, we walk about a kilometre along the stream of clear water flowing over yellowish sand. The cool water speaks of the tranquility of the surroundings. We are relaxed. However, as we look around we see the colossal damage done to nature and life. The hills, once covered with thick native forests, are bare today. Few are covered with ripe paddy, the last harvest of jumias, and which attracts elephants at night. The mention of elephants sends a chill down our spines. U Cha May Chak (37), wife of Dhung Cha who took the courage to be part of our exciting journey through the elephant habitat becomes particularly nervous as we see fresh marks of elephants’ presence around. We walk fast to quickly pass through Garjanchhara and Rangajhiri to be on high ground and safe from elephants.

|

|

Chak village in Baishari. Photo: Philip Gain

|

As we climb the hills, we stand on the top of complete destruction! The name of this place is Horinkhaiya. In every direction, the waves of hills are bare. As we look back to the northeast, the direction we came from, the vast expanse of low hills in the distance is covered with full-grown rubber trees. The hills in the distance look green and one can make the mistake of taking it as forests. In the south from Horinkhaiya, the rubber trees are hardly a year-old. Two years back [December 2008] when we passed through this area it was being cut for preparation of fresh rubber plantation. The nearby hills in the east, west and south still had coverage of native forests. Two years later we find the whole area cleared.

“Part of this area was cut last year,” says Dhung Cha Aung Chak. “This year preparation is going on for planting rubber trees.”

|

| Chak dining in Badurjhiri. Photo: Philip Gain |

Amrajhiri, an area that was still being cleared of vegetation in 2008 now has young rubber trees grown in terrace style farming on the steep hill slopes. A fence has been constructed to demarcate the rubber plantation area. As we look through rubber plantation into the east we see the greenery of some native forest patches.

Horinkhaiya and Amrajhiri are areas that used to be a safe haven for the Chaks and Marmas. They used to jum the land, hunt and gather freely. Edible plants and leaves still grow from the land devastated. U Cha May Chak (37) skillfully gathers a handful of succulent leaves of Usaithamang that will be part of our dinner menu tonight!

Into the forests!

Past Amrajhiri, we head for Badurjhiri, a small Chak village where we settle for the night. Now we see some greenery mixed up with patches of jum paddy on the high hills on the eastern horizon. As we go downhill we are thrilled at the absolute quietness and the narrow path through bushes. Ching La Mong Chak in the front of the line suddenly cries out in excitement. He has seen a red deer that disappears in the bush in the twinkle of an eye. I miss the deer; and caution Ching La Mong to stay calm the next time he sees any wildlife.

Before we reach Badurjhiri we walk past streams and bushes in fear. This is again an area where elephants pose threats to humans and domestic animals.

By the time we reach Badurjhiri, the sun is about to set. From a distance, the bamboo houses on the wooden platform in the small Chak hamlet look like dots in the greenery. A small stream flows beneath the village. The villagers have finished their washing, bathing, and day’s collection of water. U Cha May Chak wastes no time in bathing in the cooling water. Dhung Cha Aung is busy collecting wild vegetables and herbs near the stream. We are yet to realise the value of his collection.

By the time we settle in the machang house (house built on platform) of our host A Thui Chak on the slope of hill, we are at ease. We stretch our legs on the wooden floor of the one-room house with a small storeroom and an open platform on one side. The four-feet high open space under the house is where the family stores its firewood and other household materials. The hanging platform is used for washing kitchen utensils and for drying clothes.

We are soon joined by Karbari Kijari Chak (55) and engage in a chat with our host and the karbari (hereditary head of a hamlet in the CHT, traditionally nominated by the villagers, formally appointed by the circle chiefs, and acknowledged by the administration). As we have just experienced and they tell us the hamlet of 15 Chak families in 280 No. Alikhyong Mouza is a real forest village and cut off from the nearest human habitation. To reach the nearest village and Baishari Bazar one has to walk for hours.

|

|

Chak house in Badurjhiri.Photo: Philip Gain

|

All 15 Chak families in the 30 year-old village are jumias. But nowadays they cannot completely rely on jum. “The crops we get from jum are good for a maximum of six months a year. For the rest of the year we depend on the harvest of bamboo, which has also been exhausted,” says Kijari Chak. “This situation has encouraged us to engage in tobacco cultivation to earn cash.”

In 2008 when we passed through this area to go to the Mru Village Chamuajhiri, a three-hour difficult walk into the southeast from Badurjhiri, there was no tobacco there. This time when we enter the village we see young tobacco plants on the flat land that the Chaks used for production of much needed crops.

At one time the Chaks of Badurjhiri were completely dependent on jum cultivation. And they grew enough cereals from jum and the cropland for the entire year, says the karbari.

“Eight Chak villages in Baishari union still depend on jum and those depending on jum constitute approximately 20 percent of the Chaks,” says Ching Ch La of Baishari Upar Chak Para. In total there are 21 Chak villages in Naikhongchhari, Baishari, Dochhari, and Bandarban unions–all in Naikhongchhari Upazila.

The Chaks have varied reactions to tobacco being brought to the area by British American Tobacco Company. The local people refer to it as Gold Leaf, which is actually a cigarette brand of the company. The company brings cash and chemical inputs (fertiliser and pesticides), the right incentives at a time when the villagers remain unemployed for months. “Tobacco has brought us employment for the months from November when villagers have no work. Those with no grains in store can at least buy food from the markets,” says Kijari.

|

|

|

Chak woman collecting vegetable from the wild. Photo: Philip Gain

|

Elephants devouring paddy and damaging other crops are also a factor for taking an interest in tobacco. Elephants are not interested in tobacco. Elephants, the last major wildlife in the area the Chaks live in, oftentimes cause horror. In Early November 2010 elephants killed a buffalo of Badurjhiri Village. An elephant plunged its ivory three times into the stomach of the buffalo that remained tied at night. In the past elephants also killed a cow. According to the villagers of Badurjhiri there are herds of 50 to 100 elephants in the area.

The feared animal today, had enough to eat in the past. “Thirty years back, the area was a deep jungle,” says Kijari. “Man-animal fight was not like this in the past. Now the jungle is gone and the elephants go hungry and come to feed on our crops.”

Tobacco cultivation was introduced in Badurjhiri very recently in 2009 and this year 12 families are cultivating it. “Instant cash income is good from tobacco, which has expanded into the east from Badurjhiri,” says Thoai Ching Chak (30) of the village.

The Chaks of the Badurjhiri are awaiting a bigger threat that may come along with rubber cultivation. They have witnessed how rubber plantation dispersed the villagers of their neighbouring Chak village, Longoduhiri Chak Para. A Chak of Longodujhiri Chak Para, Shi Jai U Chak (40), now sheltered in Baishari Upar Chak Para, tells an appalling story of eviction of some 20 Chak families from his village that no longer exists.

Longodujhiri Chak Para was located in the northwest of Badurjhiri, about 30-minute walking distance. The village was evicted in 2002-2003. The Chak families lost their village to settlers who reportedly had R-holdings–“R” standing for refugee. One having R-holding is a settler getting land from the unclassed state forest (USF) potentially in the possession of the hill people.

“The outsiders have brought rubber on our jum land and village land and tobacco on cropland,” says Shi Jai U Chak saddened by the fact that he has become a daily labourer of a rubber plantation on land that was once the Chaks’ jum, homesteads and garden land.

“In the past there was plenty of bamboo to harvest. The outsiders have cut them all. Now there is no bamboo for us to harvest,” laments Shi Jai. “Like all others in my village, I was a jum cultivator. After losing land, we, who still remain in the area, have become day labourers. Ten families have gone to Myanmar.”

“It is our bad luck that we could not protect our land. With R-holding in hand, the Bangali settlers now cultivate rubber and tobacco on our cropland,” laments Shi Jai.

Shi Jai and none of the Chak families of the Longodujhiri Chak Para ever had settlement on their land, which they as indigenous people of the soil, had cultivated and lived on for generations.

With three sons and three daughters Shi Jai has run into difficult a situation. He has become rootless and very poor.

Fearful of invasion of rubber, A Thui Chak (30) says, “If rubber cultivation comes close to our village, our situation will be like the Chaks of Longodujhiri. We will be evicted.”

|

|

Bare hills in Baishari. Photo: Philip Gain

|

In the candle-lit room we could continue our conversation all night but we are interrupted–it is time for dinner. As we are talking and sipping home-made [rice-brewed] beverage dochoani we do not forget to take note of the meticulous preparation of the dinner items [at the corner of the room] by our host family with the assistance of Dhung Cha Aung Chak and U Cha May Chak. We already have had the taste of the Chak Cuisine, a marvel in forest villages.

All that a Chak family in a forest village needs to prepare a tasteful and healthy dinner is a chicken; everything else comes from jum and the jungle. We had to pay for two chickens. One comes on our dinner menu. The preparation of two items–soup and salad is very simple. After slaughter the whole chicken is boiled enough in water to get the best out of it for preparation of a special soup. A sour leaf, kaibotak (in Chak language), collected from the jungle is the ingredient that makes it really delicious. A dash of garlic, onion, and ginger fried in hot cooking oil and mixed with the soup make one of the finest soups one can ever taste. Then the rest of the boiled chicken sliced and mixed with chillies’ (special from jum), salt, bit of ginger and garlic makes an outstanding chicken salad. Two main items of a sumptuous dinner are ready.

Boiled for a minute or two, the green edible fern (Dhekisak) that Dhung Cha Aung Chak collected on our arrival at the Chak hamlet is to go with chilly paste. Chilly lovers will never forget the chilly paste the Chaks and other hill people make in basically two ways. One is, it is crushed in a piece of bamboo with a knot on one side (called maruthu in Chak language) with some dried fish or small prawn, salt, coriander, and lemon. Another preparation is that chilly is mashed and mixed with a particular eggplant grown in jum. A sour and soupy item made from tayongka (a sour leaf called Chupri shak in Bangla) and its flower with small prawn will add flavor and taste on your plate. Then there are boiled items–anything from banana bud to flower of silk-cotton tree. Don’t be surprised if a salad of mere succulent banana plant and dried fish with lot of hot chilly comes as a side dish. It is safe and nourishing for your stomach. Once you sip the chicken soup with all these items, you will never forget your time in a forest village. These wonderful food items, made at such little cost, have tremendous cultural and traditional value. But alas! If rubber plantation invades the jum land of the Badurjhiri Chaks, the ingredients of Chak cuisine will be lost forever.

After dinner we continue our conversation with the karbari, members of our host family and some teenagers of Badurjhiri. There is no school in Badurjhiri Village. Children who want to go to school must reside at least in Baishari. In 2010 five children from Badurjhiri stayed in Baishari to go to school. This is a difficult choice for the families to send their children to schools in Baishari.

Mong Ching Thoai Chak (19) and Keo Keo Chak (18) are two teenagers from Baishari who have studied up to class three and five and then stopped. Both are now jumia. If jum stops in the area due to tobacco and rubber they are likely to become day labourers.

Preparation for construction of a road towards Badurjhiri is making progress. This is both good and bad news for the forest villagers. With road connections established the people can move quickly and improve their market access. However, even without roads and access of vehicles, the tobacco company, rubber entrepreneurs, and land grabbers have already gone up to Badurjhiri and further into the east. With road network expanded, outsiders will come in more easily. This is very bad news for the Chaks and Mru in the remote forest villages.

As night falls we go to sleep. Nine of us sleep on the floor of the machang house hardly 10 feet x 15 feet. No space in the house is wasted. But we feel we are sleeping in the lap of absolutely quiet nature.

Next morning we take time to see a nearby jum where the chilly and all other vegetables came from to our dinner plates. The jumias grow almost everything they need. And now towards the end of jum season, they are busy collecting what remains. We get fresh chilly, tayongkai and its mature flowers to carry to Dhaka.

When we leave Badurjhiri Village and the land of the Chaks, we see something unusual for the Chak village–many men entering the village with two sacks folded on two side of a piece of bamboo. They are carrying chemical fertilizer and storing it in their houses for use in the tobacco field. Some Chak families are busy plowing and preparing their land for tobacco. We realise the invasion of modern and destructive agriculture has already happened. This is a big threat for Badurjhiri.

Rubber and Tobacco–at whose Interest?

The Chaks, Marmas, and other local residents do not want rubber in particular on the hills. “The rubber cultivators from outside have taken control of almost all land in Amrajhiri, Battalijhiri, and Tang Mang Mangjojhiri in Alikhyong Mouza (no. 280),” reports Dhungcha Aung Chak. “We are protesting against rubber cultivation in our area. Bir Bahadur MP, chairman of Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Board (CHTDB) came here and gave us his word that nobody would be evicted and everybody will stay where they are. But we do not see the sign of halting rubber.”

“Rubber has invaded the whole Baishari area. Our people are not aware. We receive allegation that rubber plantation is sometimes carried out in collusion with the headmen,” says Bir Bahadur MP.

The chairman of the CHTDB does not see anything wrong in rubber cultivation. “But what is wrong is not doing it on the land leased for the purpose,” says the chairman annoyed at the anomalous behavior of the rubber cultivators. “We have cancelled lease of 500 rubber plots (593 according to a local journalist) in Bandarban Hill District alone. The reason is those who got lease for rubber left it fallow.”

According to ZuamLian Amlai, chairperson of Bandarban Chapter of Movement for the Protection of Forests and Land Right in the CHT, the leaseholders who had their leases cancelled in 2010 retrieved 77 plots within two months. He says that many others are trying to get back their leases.

Mong Mong Chak (61), a retired high official of the CHTDB agrees with the CHTDB chairman and sees rubber as an investment in the national interest. “I am for and against rubber,” says Mong Mong Chak who comes from Baishari. “We, the Chaks have lost our land for our foolishness. We did not apply for participation in rubber.”

Mong Mong Chak is also resentful about the government authority assigned to oversee rubber plantation. “The government and the standing committee charged with rubber cultivation did not think about our well-being. It was the government policy to bring outsiders who have taken our land in the name of development.”

According to Mong Mong Chak, the leases for rubber done before the peace accord in 1997 stay valid and those who did not cultivate rubber are supposed to have their leases cancelled. “Some leases have been cancelled on paper, not in reality. There is no scope to lease land for rubber after the peace accord. Leases, if given after the peace accord, are illegal,” says Mong Mong Chak.

The Bandarban Hill District Council that is supposed to authorise any lease for rubber cultivation remains in the dark regarding on-going rubber cultivation in its jurisdiction.

Kyaw Shwe Hla, its chairman says, “We are yet to find out the status of rubber plantation–what plots have been cancelled and who are carrying out rubber plantation nowadays. All that we know is leases of some plots cancelled on paper may have gone to the same lease holders. The Bandarban Hill District Council did not authorise granting or cancelling leases.”

“We have written to the district administration to provide us information about the status of rubber plantation. We are yet to get an answer to our queries,” says Hla. “We are unable to do anything with land. What we see is many companies and individuals from outside are buying leases from the local people and taking possession of land.”

Land for rubber plantation and horticulture in Bandarban comes under the jurisdiction of three authorities–the Chittagong Hill Tracts Development Board (CHTDB), Deputy Commissioner, and the Standing Committee. The CHTDB oversees the rubber cultivation on 2,000 acres of land leased to 500 households under a rehabilitation project. These families are supposed to get land titles in their names.

A much bigger amount of land–nearly 50,000 acres–has been reportedly leased to around 1,800 individuals for commercial rubber production and horticulture. The size of an individual plot is generally 25 acres (some are up to 100 acres). The records related to the status of rubber plantation and horticulture is very difficult to get. However, what can be figured at from available records (partial) is that the majority of the individual leaseholders come from outside of Bandarban and a big percentage never initiated rubber cultivation after getting lease of land. Such lands have become grounds for anomalies and outsiders (individuals and companies) are taking advantage of this loophole.

Philip Gain is director of Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD) and freelance journalist.

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain

Hills cleared for rubber plantations. Photos: Philip Gain Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

Mountains after mountains have been cleared in Bandarban like this for preparation of rubber plantations. Photo: Philip Gain

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

His marriage was quite a story! The capture of the groom was a common enough practice then, whereby the man did not have a choice in his marriage and the arrangements were made by the parents of the bride and groom, unbeknownst to the latter. Then a few strong men from the bride’s side surreptitiously showed up to the house of the unsuspecting groom to take him captive. Starving the groom was also part of the scheme.

felling of trees. He had been charged in absentia on December 27, 2017. The court issued a warrant of arrest. On January 4, he secured a bail to stay out of jail.