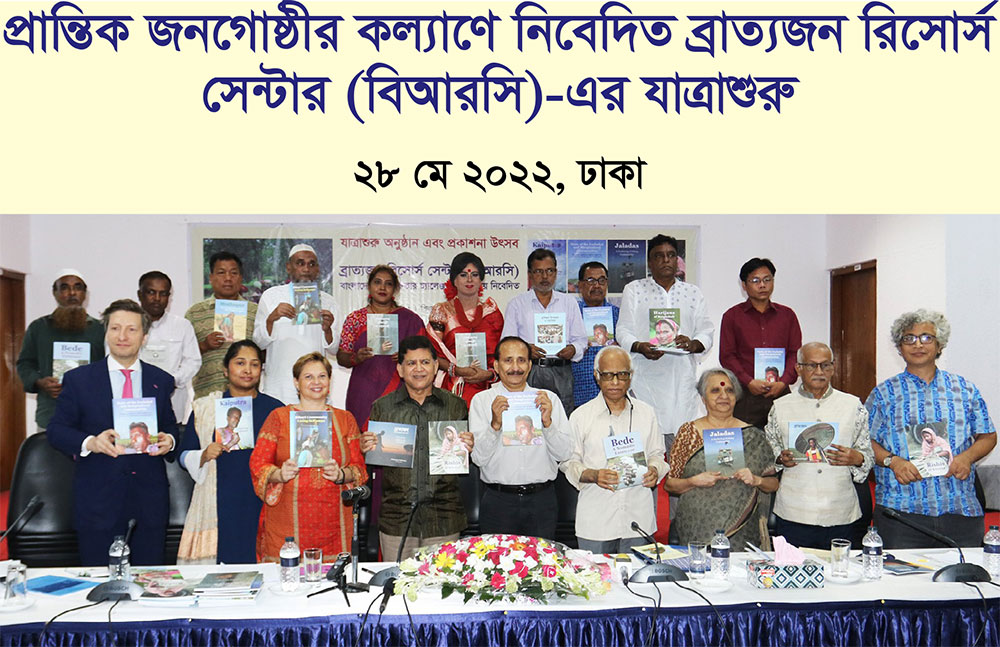

Dedicated to the marginalized and excluded communities of Bangladesh, a long-cherished national entity—Brattyajan Resource Centre (BRC)—was officially launched on 28 May 2022 in Dhaka. Eleven books and monographs and a documentary film on the marginalized communities were also launched at the event. These books, monographs and documentary film were published and produced with support from the European Union and ICCO Cooperation. Financial support for BRC comes from Caritas France and MIREREOR through a project, “Promoting human rights of marginalized groups in Bangladesh through Brattyajan Resource Centre”.

The official launching of the project, BRC and the publications marked a day of great joy for SEHD, PPRC, a great number of other organizations and communities that are associated with these and have been coming together for three decades. A strong message aired at the launching is that BRC is anchored with SEHD and PPRC but the marginalized communities are its integral part. At least 140 representatives of all nine groups of marginalized communities the center is devoted to, human rights defenders, community organizations, civil society, economists, trade union leaders, academia, journalists and foreign diplomats joined the launching. A true festive atmosphere filled the air of the conference hall of CIRDAP in Dhaka the launching venue.

The official launching of the project, BRC and the publications marked a day of great joy for SEHD, PPRC, a great number of other organizations and communities that are associated with these and have been coming together for three decades. A strong message aired at the launching is that BRC is anchored with SEHD and PPRC but the marginalized communities are its integral part. At least 140 representatives of all nine groups of marginalized communities the center is devoted to, human rights defenders, community organizations, civil society, economists, trade union leaders, academia, journalists and foreign diplomats joined the launching. A true festive atmosphere filled the air of the conference hall of CIRDAP in Dhaka the launching venue.

The organizers of the event—SEHD and PPRC—welcomed the audience with a message that communities with different vulnerabilities have come to a celebration of working together for decades and that we should not see them as victims. They have many potentials, strengths, diverse culture and language.

In his keynote address Philip Gain, the program director of BRC, explained the background of BRC, how the communities it is devoted to are its bona fide participants, its goal and mission.

The communities that Brattyajan (meaning marginalized people) Resource Center is devoted to include but not limited to are Adivasis (ethnic communities), tea workers (80 communities), sex workers, transgender, Bede, Harijan, Rishi, Kaiputra, Jaladas and Bihari.

(ethnic communities), tea workers (80 communities), sex workers, transgender, Bede, Harijan, Rishi, Kaiputra, Jaladas and Bihari.

“The launching of BRC and books is a big celebration because it is founded on concrete knowledge resources—books, monographs, investigative reports, documentary films, photographs, etc. that anyone can easily access” noted Gain. “These knowledge resources are outputs of our investigative reporting, action research, survey, video documentation, photography and analysis.” He explained how these have been developed with active participation of communities and all other stakeholders and what are contained in these publications. The most significant aspect of these publications and productions on which BRC is founded is that SEHD and partners have mapped and defined almost all communities it is devoted to, issues and unique situations they face. That these publications and productions have had an influence on policies and strategies of World Bank, Asian Development Bank, United Nations, state agencies and NGOs in some areas (forest, fisheries, open pit, tea workers’ wages, etc.) are supported by evidences. These also reflect the trust of communities, academia and professionals at different levels.

Now the mission of BRC is to keep updating knowledge resources on the excluded and marginalized people, develop group- and issue-specific agenda, carry out research and investigation to expedite access of the excluded and marginalized communities to social protection, scale up skills and capacity of different actors, facilitate dialogues and interactions at different levels, fill in the information gaps, build right attitude towards information and scale up the use of knowledge resources at all levels, contribute to changes for better in the lives of excluded and marginalized communities, etc.

Community voices shared by 10 speakers from nine groups was a striking part of the launching celebration in that they all shared their personal and community experiences with SEHD and PPRC in research, investigation, building knowledge resources and how knowledge resources have strengthened them and their communities. Their unanimous trust: with accurate information and knowledge in hand they can assert their rights and can influence the state- and non-state parties who make crucial decisions. BRC can play a precise role in assisting them with information and guidance. They also shared their expectations from BRC.

The community voices at the launching were represented by Rambhajan Kairi, executive adviser, Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union; Saud Khan, Bede leader, Munshiganj; Eugin Nokrek, president, Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad; Zuam Lian Amlai, human rights activist, Chittagong Hill Tracts; Shiung Khumi, human rights activist, Chittagong Hill Tracts; Aleya Akhter Lily, president, Sex Workers’ Network; Milon Kumar Das, executive director, PARITTRAN; Krishnalal, president, Bangladesh Horijan Yokkho Parishad; M. Shoukat Ali, general secretary, Stranded Pakistanis General Repatriation Committee; and Ivan Ahmed Katha, Shachetan Hijra Adhikar Shangha. (For summary of what they shared see Annex in the bottom of this report).

Professor Wahiduddin Mahmud, the chief guest at the launching, criticized the government for not doing enough for the marginalized communities and spoke on the ethics and strategies on their protection. “

The government has failure in making right policies and plans for protection and progress of the marginalized communities,” said the leading economist of the country Prof. Mahmud. “The marginalized communities are far left behind than the average citizens of the country because the government failed to adopt appropriate policies and measures for them.”

“The idea and development process reach the average Bengali citizens easily regardless of their classes. However, when it comes to the indigenous communities and other marginalized groups, identities and class barriers pose a huge problem. This is a failure of our government,” observed Prof. Mahmud.

“It is not just that the government failed to bring development discourses to the marginalized communities, it has not thought judiciously even to slightly change ideas and life skills for their life and livelihood. Many plans and measures have been adopted in Bangladesh for development, but instead of taking plans for economic development of the marginalized communities, barriers have been put in place,” explained Prof. Mahmud.

“An irony is that environmental preservation is prioritized in sustainable development goals (SDGs), but these communities whose occupations are directly linked with nature and environment are neglected and deprived,” further explained Prof. Mahmud.

In this intricate nature of deficient policies and practices for progress of the marginalized communities Prof. Mahmud directed his thought to them: “The goal of our work is that you are not called marginalized in the future. You shall be considered integral part of the mainstream population without losing your diverse and unique culture, languages and identities. And believe you have been constructively contributing to the development of Bangladesh.”

On research and publications launched Prof. Mahumud said, “The publications that have been presented today are very informative. These are not outputs of conventional research. These are authentic documentation after intensive field-based observations and analyses on your life and livelihood which make the follow-up research and documentation easy.”

On research and publications launched Prof. Mahumud said, “The publications that have been presented today are very informative. These are not outputs of conventional research. These are authentic documentation after intensive field-based observations and analyses on your life and livelihood which make the follow-up research and documentation easy.”

“The publications of SEHD and PPRC have brought many policy issues in the front and have led to dialogues with the government. The government bodies engaged in various surveys and producing data should compare the kinds of data and analyses of BRC for best results,” stressed Prof. Mahumud who chairs and advises many government bodies. “I will be part of BRC” was affirmed Prof. Mahmud.

Jeremy Opritesco, Deputy Head of Mission, Delegation of the European Union to Bangladesh, spoke as a special guest at the event. “The launching shows a strong involvement of the communities in BRC and participants at this launching event,” said Mr. Jeremy. “With the SDG goal, leaving no one behind, the BRC has been launched at a perfect time. The marginalized communities are left behind. It is important to fight for their rights and inform them of their rights. We are proud that EU has supported this initiative. The knowledge outputs will be helpful for strategic actions. Discrimination based on gender, religion, sexual orientation, community, language and occupations exists. We also emphasize food security of the marginalized communities.”

as a special guest at the event. “The launching shows a strong involvement of the communities in BRC and participants at this launching event,” said Mr. Jeremy. “With the SDG goal, leaving no one behind, the BRC has been launched at a perfect time. The marginalized communities are left behind. It is important to fight for their rights and inform them of their rights. We are proud that EU has supported this initiative. The knowledge outputs will be helpful for strategic actions. Discrimination based on gender, religion, sexual orientation, community, language and occupations exists. We also emphasize food security of the marginalized communities.”

Dr. Lilly Nicholls, High Commissioner of Canada to Bangladesh, another special guest gracefully shared her thoughts after listening to the community voices. She directed her messages to the marginalized communities as, “Thank you for teaching me about the discriminations you face for your language and cultural identities. The most impressive is that you are putting forward suggestions. We are deeply committed to elimination of discrimination, exclusion and feminist approaches.” On her country she said, “Canada is a country, where people take shelter, fleeing from violence. It has high tolerance towards diversity.”

Khushi Kabir, a noted feminist and development actor applauded the launching of BRC and said the centre is inclusive of communities and other stakeholders. “The research SEHD conducts is highly involved with the communities. It is an important centre for conveying information to society, policy makers and journalists,” said Ms. Kabir, “and these can be very useful in organizing in-depth discussions with communities and targets.”

Khushi Kabir further observed BRC should pay special attention to land rights of the marginalized communities. Many do not own any land and do not own home they live in. “I will be part of BRC,” was her precise commitment.

Professor Md. Golam Rahman, editor of Ajker Patrika, former chief information commissioner and a member of SEHD talked particularly on inclusiveness and integration of the marginalized communities who are generally isolated because of their ethnic identities and occupations. “We all are people of this country and everyone should get equal attention but for those who are left behind deserve preferential discrimination,” observed prof. Rahman. “Movements bring the problems in the forefront, but the root causes and purposes sometimes get lost in the process of change. Bureaucracy inhibits the revitalization and mobilization of these causes. Building true databases, a commitment of BRC, can play a significant role here.”

because of their ethnic identities and occupations. “We all are people of this country and everyone should get equal attention but for those who are left behind deserve preferential discrimination,” observed prof. Rahman. “Movements bring the problems in the forefront, but the root causes and purposes sometimes get lost in the process of change. Bureaucracy inhibits the revitalization and mobilization of these causes. Building true databases, a commitment of BRC, can play a significant role here.”

While Prof. Tanzimuddin Khan of Dhaka University and member of SEHD gave the welcome address, Dr. Hossain Zillur Rahman, research and resource adviser of BRC, executive chairman of PPRC and Chairman of BRAC Bangladesh chaired and facilitated the discussion.

Dr. Rahman’s summary of discussion highlights some of the pertinent issues with the excluded and marginalized communities, many of them invisible. In his introductory remarks, Dr. Rahman said the launching is an occasion for communities to come together and talk about the challenges they face. One obvious challenge is to make them visible to the mainstream population and also to make their strengths and capabilities visible.

“We want concrete progress for these people through research and result-oriented actions. We are celebrating the work of the last thirty years,” said Dr. Rahman. “However, we need to keep in mind they are different in their vulnerabilities. Yet they are united by their marginality. BRC highlights the nature of their unitedness.”

“We want concrete progress for these people through research and result-oriented actions. We are celebrating the work of the last thirty years,” said Dr. Rahman. “However, we need to keep in mind they are different in their vulnerabilities. Yet they are united by their marginality. BRC highlights the nature of their unitedness.”

He emphasized on the keynote speaker Philip Gain’ contention that BRC is a learning and collaboration centre. A clear expectation from BRC is that it will be a knowledge centre and a platform of voices.

In relation to tea workers’ condition he said, “We need to understand the economic dimension of wage deprivation. In relation to Bede, we need to understand social discrimination and deprivation. The Bedes need a new footing in the age of urbanization and development.”

On the concerns of the forest people he observed that the forest-dwelling communities have been alerted about the importance of data. This is a great realization that we have brought to them.

On Milon Das’ deliberation on Rishi community, Dr. Rahman pointed out, “He has highlighted additional issues. They have been stereotyped as fit for menial jobs. Social discrimination happens based on social perception. There has been continuation of social discrimination to their next generations.”

On Milon Das’ suggestion that a lifestyle museum for saving their culture be established apart from their statistical representation he said, “In future this can be an additional task for BRC.”

On Harijans, his observation: Every community faces different facets of discrimination. Harijans are the traditional city and municipality cleaners. Most recently, the discrimination they face is the loss of jobs. This job was reserved for the community–now they are not the priority anymore. Harijan leader Krishnalal’s expectation is right representation of their community in the BRC. They hope for an accurate population count in the upcoming census”.

“The Biharis, confined to camp life, are victims of political discrimination. They have specific problems. We have scope of advocacy with the government for their rehabilitation and education,” observed Dr. Rahman.

He put emphasis on the keynote speaker’s argument that BRC is a driver of results. It is not limited to any project. It will continue to exist beyond projects.

The timing of the launch of BRC is perfect as eight years are left before SDGs’ timeframe comes to an end. Leaving none behind is a priority agenda of SDGs. It will be a huge step forward for their visibility if they are included in the census.

Annex: Community voices

Rambhajan Kairi, executive adviser, Bangladesh Cha Sramik Union

We have been working for the progress of our tea communities. But we have limits, particularly in exposing our condition and difficulties through research work. Research is difficult but crucial to highlight our needs and rights. BRC can help us raising our voice and reaching the concerned government bodies. A tea worker’s daily wage is stagnated at Tk.120 (1.36 USD) since 2019. The minimum wage board set up in 2019 to fix the minimum wages for the tea workers, has been frozen to date (June 2022) after a failed attempt to even reduce existing facilities and wages we, tea workers, get. This is a shame. The right to paid leave was previously unknown to the workers. They started getting the weekly paid leave only from 2017.

difficulties through research work. Research is difficult but crucial to highlight our needs and rights. BRC can help us raising our voice and reaching the concerned government bodies. A tea worker’s daily wage is stagnated at Tk.120 (1.36 USD) since 2019. The minimum wage board set up in 2019 to fix the minimum wages for the tea workers, has been frozen to date (June 2022) after a failed attempt to even reduce existing facilities and wages we, tea workers, get. This is a shame. The right to paid leave was previously unknown to the workers. They started getting the weekly paid leave only from 2017.

What is unique of SEHD is it has been giving priority to our communities for the last 15 years in its research and investigative work. The tea workers need protection of their rights and benefits. In general, they are not aware of their rights. BRC can play a precise role with information in communicating with the state- and non-state organizations.

Brief profile of tea workers and tea communities:

There are 158 tea gardens in Bangladesh (excluding those in Panchagarh where tea cultivation started only recently). The majority of 138,366 tea plantation workers and their total population of around half a million are non- Bengali. The British companies brought them from Bihar, Madras, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh and other places in India to work in the tea gardens in Sylhet region. There are as many as 80 tea communities in the tea gardens who speak as many as 13 languages. The current (2022) daily cash pay of a tea worker is Taka 120.

Saud Khan, Bede leader, Munshiganj

The people of the Bede (gypsy) community are victims of violence and neglect without end. We gained the right to vote only in 2007. Our social image is poor. People look down upon us. They see us as inferior beings. We are Muslims and Bengalis. We have learned through research that we are deprived of our rights. We need education and diverse job opportunities to migrate out of our current condition.

We do not have land for cultivation. We need help from the government and NGOs. We have little interaction with the educated people. Educated Bedes ignore their own community to avoid getting labelled and losing their jobs.

Today I can speak in a forum like this because of my participation in research and because of such events. Our aim is to get our voices and demands heard and considered by the state- and non-state actors.

Brief profile of the Bede people: The Bede is a Muslim gypsy (floating) community of Bangladesh. They travel from one place to another to earn a living for 10 to 11 months of the year and gather in 75 locations of the country to meet their families and other community members for one to two months. Many Bede leaders estimate their population in Bangladesh at around 500,000 and around 5,000 caravans (groups) of Bede moving from one place to another. The Bedes in general are very poor and the rate of literacy among them is very low as well. Most of them are landless and many live on khas (public) land and in tents. They hardly have access to healthcare services and other government benefits including Social Safety Net Programmes (SSNPs).

Eugin Nokrek, president of Joyenshahi Adibashi Unnayan Parishad

We, the Garos and Koch, of Modhupur forest villages consider ourselves to be autochthons in the area. But sadly enough we are denied of our customary rights. In Modhupur forest villages there are around 20,000 Garos almost entirely converted to Christianity and 3,500 Koch, all Hindus. We see Philip Gain treading the forest villages from 1980s. He and SEHD have been deeply involved in research and investigation on forestry issues and our condition. SEHD’s recent book, Modhupur: The Vanishing Forest and Her People in Agony, is a landmark publication for us. It provides comprehensive information on Modhupur and its first people. As we use the book, we realize the significance of research, investigation and analysis.

We, however, lack skills of generating and using knowledge to properly represent our communities and our demands. SEHD has been training us on research techniques and gathering data from the field. Now we are better oriented in using the books, reports, documentary films and photos on Modhupur. These are very helpful for meaningful advocacy. I trust, with BRC established, SEHD, PPRC and we can work together for our rights. We now better understand how to have an influence on state agencies with information in hand.

Brief profile of the Modhupur forest and its people:

Size of Modhupur upazila is 91,545.131 acres (370.47 sq. km) of which 45,565.18 acres are forest land of which 11,671.21 acres are reserved forest, 20,837.23 acres Modhupur National Park, 7,800 acres rubber plantation and 5,000 acres social forestry (estimated). Current estimated forest cover is 9,000 acres! Population in Modhupur upazila is 296,729 (2011 census) of which 17,327 are Garos (SEHD survey 2018) and Koch or Bormon are 3,427 (SEHD survey 2012). Garo population in Muktagachha, Fulbaria and Jamalpur Sadar upazilas surrounding Moddhupur upazila is 1,963 or 486 households (SEHD inventory 2018). Koch or Barmon population in Muktagachha and Fulbaria upazilas is 517 or 128 HHs (SEHD inventory 2018). Sources: Government website (modhupur.tangail.gov.bd/), Forest Department of Bangladesh, SEHD survey 2012 and 2017-2018.

Zuam Lian Amlai, Bawm representative and human rights activist, Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT)

I am involved with SEHD from 1997-1998 and familiar with its research on the CHT environment, culture and people. Its survey on Chak and Khumi and publications on these communities give us baseline data. We want similar surveys on other communities such as Mro and Bawm. We can efficiently administer our villages with baseline data in hand. If we have primary information in hand, we can make informed opinions and better engage in movements for rights.

I am involved with SEHD from 1997-1998 and familiar with its research on the CHT environment, culture and people. Its survey on Chak and Khumi and publications on these communities give us baseline data. We want similar surveys on other communities such as Mro and Bawm. We can efficiently administer our villages with baseline data in hand. If we have primary information in hand, we can make informed opinions and better engage in movements for rights.

The documentary film, ‘Chokoria Sundarban: A Forest without Trees’ of SEHD is a stunning articulation of realities of horrible destruction of mangrove forests and those in the CHT and elsewhere. We, in the CHT, are in a state of panic. We have serious issues with the CHT Regulation that has been drastically scrapped. We know BRC cannot solve all our problems but research and publications of SEHD can educate the CHT people on their rights. We cannot play an effective role without information.

Shiung Khumi, a representative of the Khumi community, added to discussion of ZuamLian Amlai. SEHD carried out a household survey on our Khumi community. Our main difficulties include but not limited to are we are left behind in education because of remoteness, our economic condition is poor and we are losing our land. According to the 1991 government census, the Khumi population in Bangladesh was 1,241, but according to the SEHD study conducted in 2014 the Khumi population was 2,899. The people of the Khumi community are concentrated in Thanchi, Ruma and Roangchhari upazilas in Bandarban Hill District. Ten Khumi families live in Bilaichhari upazila in Rangamati district and just one family in Bandarban Sadar.

SEHD carried out a household survey on our Khumi community. Our main difficulties include but not limited to are we are left behind in education because of remoteness, our economic condition is poor and we are losing our land. According to the 1991 government census, the Khumi population in Bangladesh was 1,241, but according to the SEHD study conducted in 2014 the Khumi population was 2,899. The people of the Khumi community are concentrated in Thanchi, Ruma and Roangchhari upazilas in Bandarban Hill District. Ten Khumi families live in Bilaichhari upazila in Rangamati district and just one family in Bandarban Sadar.

Brife profile of the CHT and its People: At 13,295 square kilometers or 10 percent of Bangladesh, the area is mountainous contrasting greatly with the rest of Bangladesh in geography and human habitation. It is the home to 11 distinct indigenous communities—Chakma, Marma, Tripura, Lushai, Bawm, Pangkho [also spelled as Pangkhua or Pangkhu], Mro, Khumi, Chak, Khyang and Tangchangya. The Bengali population was very small—around 2.5 percent—even at the time of independence from the British rule in 1947, which rose to 48.57% in 1991 (1991 population census) from 10% in 1951 and 35% in 1981 (Schendel 1992:95). According to 2011 population census the population of 27 ethnic communities of Bangladesh stood at 1,586,141, which was 1.1% of the population back then. Of them ethnic population of the CHT was 845,541 and the ethnic population in the plains land was 740,600 (Moral, 31 August 2013, Prothom Alo). The list revised in 2019 has listed 50 ethnic communities with no change in number in the CHT. There is no government statistics on communities added to the official list.

Aleya Akhter Lily, president, Sex Workers’ Network SWN)

We are involved with SEHD for years in research. I was personally involved with a study on brothel-based and street sex workers. Our sufferings are endless. Our life is a war. We are constantly subject to violence. The sex workers and their children are excluded from the mainstream society. The children of the sex workers face many difficulties to get admission in schools. I hope that sex workers will gradually be accepted in the mainstream society. BRC should function as a repository and it should play the role of a facilitator for us to become equal and dignified citizens. SEHD is indeed a pioneer in research and publications on the sex workers.

Brief profile of Sex workers: SEHD, in its study of 2018, found 3,721 female sex workers (FSWs) in 11 brothels. According to government and other sources the total number of FSWs is much bigger in the country—around 93,000. Of them, 36,593 are based in the streets, 36,539 in residences and 15,960 in hotels. There is also an estimated 119,869 MSM (men who have sex with men) including transgender (TG)/Hijra (approximately 10,000).

Milon Kumar Das, executive director, PARITTRAN

People of the Rishi community are generally considered untouchables by mainstream Bengalis. We, 400,000 Rishis, live in Satkhira, Khulna and Bagerhat districts. We are considered untouchables and are victims of routine deprivation and repression. We have not been able to be part of any large scale research or report to date. We do not have access to education. Our children are compelled to do menial jobs such cleaning toilets at schools, even though there are cleaning staff. This is an insult to our children that puts pressure on their psyche. From 2007 we demanded discrimination elimination law but what the government has given (anti-discrimination law) us is not helpful at all. We make significant contribution to revenue but we do not get what we should. We want a museum for preserving our culture that is near extinction. Our expectation from BRC is that it gives our community a visibility.

Brief profile of Rishi people:  Historically the Rishis of Bengal are cobblers, leather workers and instrumentalists for generations. The people of this ‘untouchable’ community mostly live in India’s Uttar Pradesh, Maddhya Pradesh and Bihar regions. They are one of the repressed or ‘Dalit’ communities among the Hindus in India. Currently, the Rishi people live in almost every district of Bangladesh. Their number is, however, higher in Jashore, Satkhira, Khulna and Bagerhat districts. Parittran, a rights- based organization of the Rishis in Bangladesh, Rishi population in the Khulna division alone is around 186,797. Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC), with assistance and guidance of SEHD and Parittran, carried out a research in 53 paras (clusters) or villages in Satkhira, Jashore, Khulna and Bagerhat districts of Khulna division and found 51,745 Rishis in 9,088 families.

Historically the Rishis of Bengal are cobblers, leather workers and instrumentalists for generations. The people of this ‘untouchable’ community mostly live in India’s Uttar Pradesh, Maddhya Pradesh and Bihar regions. They are one of the repressed or ‘Dalit’ communities among the Hindus in India. Currently, the Rishi people live in almost every district of Bangladesh. Their number is, however, higher in Jashore, Satkhira, Khulna and Bagerhat districts. Parittran, a rights- based organization of the Rishis in Bangladesh, Rishi population in the Khulna division alone is around 186,797. Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC), with assistance and guidance of SEHD and Parittran, carried out a research in 53 paras (clusters) or villages in Satkhira, Jashore, Khulna and Bagerhat districts of Khulna division and found 51,745 Rishis in 9,088 families.

Krishnalal, president, Bangladesh Horijan Yokkho Parishad We call ourselves Harijans. We use this word instead of Dalit because we consider the word ‘Dalit’ as an insult. We have been cleaning Dhaka and other cities for generations. Yet, currently only 30 percent of the cleaners in Dhaka City Corporation are Harijans. Day by day we are losing our traditional jobs. In paper we are to get 80% of the cleaners’ jobs in municipalities but in reality we get only 8%. We sent letters to the government regarding this. We live on government land. We are a totally landless community. The Dhaka City Corporation promised us to give apartments in building on state-owned land. However, only those who have jobs as sweepers can access these apartments.

We call ourselves Harijans. We use this word instead of Dalit because we consider the word ‘Dalit’ as an insult. We have been cleaning Dhaka and other cities for generations. Yet, currently only 30 percent of the cleaners in Dhaka City Corporation are Harijans. Day by day we are losing our traditional jobs. In paper we are to get 80% of the cleaners’ jobs in municipalities but in reality we get only 8%. We sent letters to the government regarding this. We live on government land. We are a totally landless community. The Dhaka City Corporation promised us to give apartments in building on state-owned land. However, only those who have jobs as sweepers can access these apartments.

Brief profile of Harijans: Harijan is an occupational group or community. They are traditionally known as sweepers and many of them consider themselves as social outcasts or ‘Dalit’. The term, ‘Dalit’ is used to define the status of those who are outside the four varnas, which means they belong to the so-called fifth category in the Hindu casteism. The members of the Harijan community work as cleaners in the cities and pourashavas (municipalities) all over the country except for three districts of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT). Like the tea workers, the members of the Harijan communities were brought to what is now Bangladesh from India’s Odisha, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh regions during the British colonial period. Cleaning has been their main occupation for more than 200 years now. The Harijans with a population of around 100,000 are one of the most marginal communities who are afflicted with a variety of social and economic problems.

M. Shoukat Ali, general secretary, Stranded Pakistanis General Repatriation Committee

We, Biharis, live in 70 camps in 13 districts. Our living condition was good before the liberation. In camp life, we do not have dignity as human beings. In camps a family generally gets a small room (8 feed X 8 feet). We have no privacy. Around 5,500 families living in the Geneva alone who use 150 common bathrooms. For six camps in Mohammadpur area of Dhaka city including Geneva Camp there is just one school. The children do not get proper learning atmosphere. Yet, I am hopeful that the prime minister of Bangladesh will keep her promise to rehabilitate us.

Brief profile of Bihari people: Approximately 300,000 Urdu-speaking Biharis live in 70 camps of which 28 are located in Dhaka. The Biharis, who migrated to what is now Bangladesh during the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947 sided with Pakistan during Bangladesh’s liberation war in 1971. After the war, a portion of them went to Pakistan and the rest remained stranded in Bangladesh. The High Court of Bangladesh, in a 2008 judgement, gave a ruling in favour of giving citizenship to around 150,000 Biharis who were minors in 1971 or born afterwards. However, they still live an inferior lives in the camps without a permanent address and basic facilities. They are continuously deprived of most of their political, economic, social, and cultural rights.

Ivan Ahmed Katha, Shachetan Hijra Adhikar Shangha

Bangladesh government recognized the Hijra community and gave us the third gender status in 2013. We do not know the budget of the government for us. We want to be informed of how much funds we are entitled to and how much we have actually received. I am doubtful we are getting the financial benefits allocated for us. The Hijra community should be able to continue their key traditional occupations that include but not limited to—badhai tola (collection of money in exchange of blessing to newborn through performing dances and songs); cholla manga (collection of subscription from market) and sex work—without barriers. Now the Hirjas collect money from busses and other vehicles. They also beg subscriptions in different festivities. We cannot buy land and houses. We rarely have enough food. Another important point is I have been involved in census and I have seen that there is no mention of any gender other than men and women. (BBS however, informs that in the population census of 2022 the Hijras will be enumerated separated).

Brief profile of Hijra people: A study, ‘Mapping Study and Size Estimation of Key Populations in Bangladesh for HIV Programs 2015-2016’ of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Government of Bangladesh, in collaboration with Save the Children and UNAIDs, has estimated the TG or Hijra population from as low as 6,867 to the maximum of 10,199. According to the study maximum percentage of the Hijra (35%) are concentrated in Dhaka followed by Sylhet (17%) and Chattogram (16%). According to the study, a large percentage of the TG/hijra (77.7%) identified themselves as sex workers.

Report by Philip Gain, Arpita Das and Nurina Durba Gain | PDF: Bangla | English